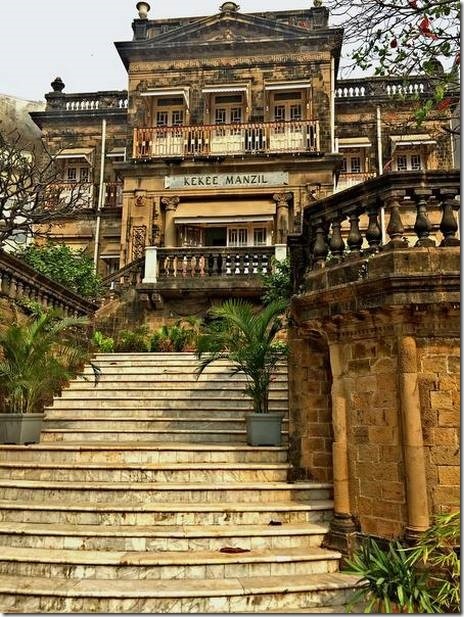

Kekee Manzil – The House of Art chronicles a micro-history of the city anchored in a century-old family home

Filmmakers Behroze Gandhy and Dilesh Korya’s documentary, Kekee Manzil – The House of Art offers a glimpse into the interiors of a heritage home, shedding light on its iconic residents Kekoo and Khorshed Gandhy. Kekoo established the only picture-framing company in Asia in the 1940s and later opened the city’s first contemporary art gallery, Gallery Chemould, now known as Chemould Prescott Road, run by his daughter Shireen Gandhy. The documentary captures how Kekoo and Khorshed displayed compassion during challenging times, stayed true to their secular ideals, and remained engaged civically, while building frameworks within which art could grow in postcolonial India.

Article by Pooja Savansukha | The Hindu

In an interview with The Hindu, Behroze shares how despite the fact that her grandfather, who built the house (naming it after Kekoo) was a traditional Parsi patriarch, Kekoo invited all kinds of people home. “It was a source of much amusement to us as kids watching our grandfather’s face, as various folk used to troop through,” she shares. Later, Kekoo opened up his home as a space for community meetings, for artists to live and practise in, and as a place of refuge. The bungalow, located in a secluded sea-facing neighbourhood, became a site where the socio-political and artistic climates of the city were nurtured.

At the beginning

UK-based Behroze, grew up in Kekee Manzil and moved to London when she was 19. In her mid-thirties, while producing the show, On The Other Hand in the UK that dealt with South Asian issues, she realised, “How connected [her] father was as [she] had access to guests from every walk of life.” She elaborates, “When the riots in Bombay exploded after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, I was commissioned to do a show in Delhi. This was when my father was busy with the Peace committees in Bombay and our work interconnected.”

She began recording her parents in 2002, realising how they were a repository of the early years of the Indian art movement. She also interviewed their contemporaries – members of the Progressive Artists’ Group including SH Raza, Akbar Padamsee, and Krishen Khanna. She took a short hiatus after her parents passed away between 2012-13, but soon began examining the material she had access to. Despite losing footage and being unable to clean-up profound interviews like the one with artist Ram Kumar, she had enough to construct a narrative in close collaboration with Korya that featured family members, friends, and old archives from 8 mm film.

She says, “The story was a curious one — of how my father, a casualty of the Second World War, as far as his incomplete studies at Cambridge were concerned, landed up being one of the catalysts of an art movement, which was totally at odds with his family’s Parsi business background. It all revolved around a shop selling picture frames and a series of curious co-incidences which led him to the point of opening Gallery Chemould.”

Korya persuaded Behroze to embody the narrative voice in the film. It’s a powerful choice that adds sensitivity to the story. She narrates Kekoo’s life, acknowledging how her distance from Mumbai gave her a necessary “insider-outsider perspective.” “Kekoo was excited I was filming him; he felt like someone was taking him seriously in his old age,” says Behroze adding how Salman Rushdie, Nalini Malani, and Anish Kapoor instantly agreed to be interviewed for the film, a testament to his influence.

Family and friends

Intimate family scenes around the dining table and living room highlight the joint-family life in Kekee Manzil. Behroze’s siblings Adil (who runs Chemould Frames), Rashna, and Shireen, Kekoo’s brother Rusi, as well as the eldest surviving family-member, his cousin, Dara feature prominently. Behroze says, “I wanted to bring out how crucial my mother was in running a gallery like Chemould. We try to address this in the way my siblings and artists like Nalini Malani speak about her contribution, but somehow my father dominates the film.” Kekoo, she describes was chaotic, “Khorshed had the persistence to see his visions through.” The musical score of the film, produced by Talvin Singh, evokes the Indian classical music that Khorshed sang in the house every Thursday, or listened to frequently. While Khorshed is absent physically in much of the film, she is entirely present through the music.

The film narrates Kekoo’s chance encounters in the city, with Italian prisoners of war who educated him in art, Jewish emigres who escaped Nazi Germany, and Belgian businessmen who wanted to invest in pictureframe moulding. Kekoo’s meeting with Austrian artist Walter Langhammer was transformative; through him, Chemould Frames on Princess Street became a hub for artists. It led to Kekoo meeting the Bombay Progressives. The Gandhys’ close friendship with MF Husain is highlighted — although their conflicting stances following Indira Gandhi’s Emergency strained their relations, they later reconciled.

“Something I learnt about my father is that he interacted with people at a human level. He would talk to the local sweeper, policeman, neighbours, strangers on the streets; he never made distinctions. He was wildly impractical and helped those in need at his expense,” says Behroze. She acknowledges how his phases of depression during his later years were times when she spent reflective moments with him. She did not see his bi-polar disorder as a disease, “If he gave so much, he had to be able to recharge himself.”

Art and politics

The film transports viewers to an old-world city — scenes in a quieter Bandra, Juhu Beach where the Gandhys would go swimming, and other parts of the city evoke simpler times. Kekoo and Khorshed watched the city develop, witnessed historic moments of optimism and disillusionment, and simultaneously built relationships with artists grappling with the times. It showcases Tyeb Mehta who was offered a solo exhibition at Gallery Chemould in 1964, “became known as the conscience of the nation.” Over the years, as the Gandhys witnessed the city transform topographically, they also found their ideals come under threat during crises like the Emergency and the Mumbai riots. For the Gandhys, secularism and freedom of speech were paramount. Kekoo showcased exhibitions at his gallery that embraced abstractionist, narrative, and conceptualist perspectives, featuring works by Vivan Sundaram, Nalini Malani, Gieve Patel, Mehlli Gobhai, and Rummana Hussain, among others. These artists reflected upon the events around them, challenged injustices, and even, as in the case of Bhupen Khakhar, “Scandalised the artworld with sexual depictions featuring his long-term partner, Vallabhai.” The documentary, for us is then a reminder that the fabric of art is intrinsically tethered to socio-political happenings.