Mahomed Ghyasoodeen’s account, published in 1817, remains a prototype for the numerous biographies of the city that continue to be written 200 years on.

Article by Murali Ranganathan | Scroll

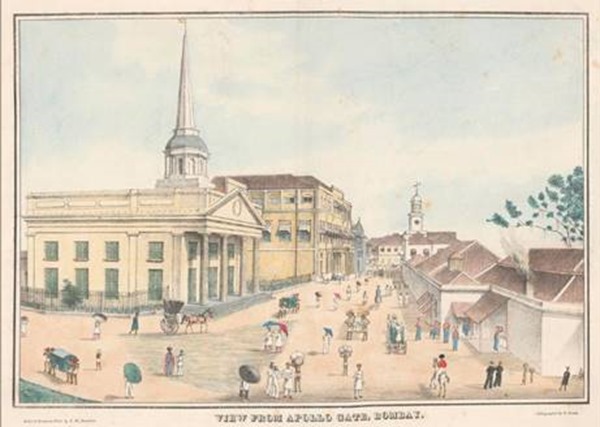

“View from Apollo Gate, Bombay”. | R Prera after JM Gonsalves, from Views at Bombay, Bombay, 1831, hand-colored lithograph. In public domain, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The city of Mumbai, one of the largest urban conurbations in the world, has been the subject of hundreds of books in the past few decades. This is not a new phenomenon and can be traced back to the 16th century.

The earliest mention of the island of Mumbai is by Garcia da Orta in his Portuguese book Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India first published in Goa in 1563 and one of the first books to be printed in India. Orta mentions “Mombaim, land and island, where the King our Lord has made me a grant, a long lease”, and waxes eloquent about the luscious mangoes that grew on the island. And, doubtless, many other Portuguese books from the 16th and 17th century have mentioned the island.

After the island of Mumbai changed hands in the 1660s, the English began writing about their new acquisition with a passion that no other city, except London, could invoke in them. Both visitors and residents were constantly writing and publishing about the city and its phenomenal growth.

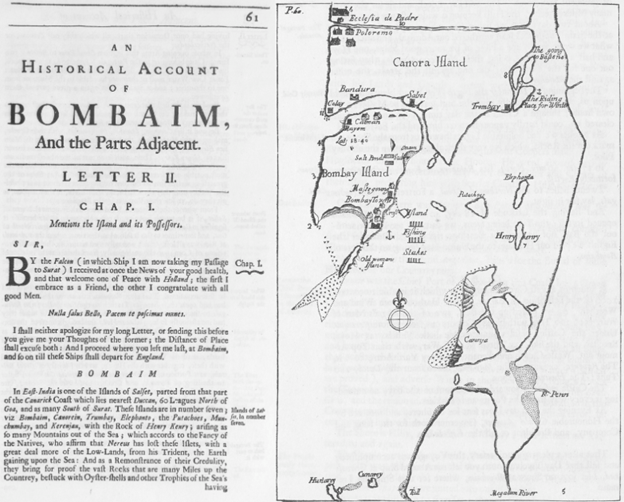

One of the first to write about the city after an extended stay was Dr John Fryer, surgeon with the East India Company, who first arrived in Mumbai in 1673. A new account of East-India and Persia, in eight letters being nine years travels begun 1672 and finished 1681 (published in 1698), contains an extensive description of the city, its denizens, and its geography.

Fryer, John, -1733. A new account of East India and Persia in eight letters: being nine years travels, begunand finished 1681. Delhi: Periodical Experts Book Agency, 1985. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Fryer was followed by John Ovington, a chaplain on a ship owned by the East India Company, who visited Mumbai on his way to Surat. His A Voyage To Suratt In The Year 1689 (published in London in 1696) contains a brief account of the city, especially the monsoons. Ovington describes the great morbidity among Europeans in Mumbai, and notes that this had birthed a proverb among the English: “Two Mussouns are the Age of a Man”.

John Henry Grose, who visited the city in the 1750s, describes his long stay on the island and “the fortifications, public works and buildings of Bombay,” in his book A Voyage to the East Indies (published 1757). Perhaps the most sumptuous book to emerge from this early period is the richly illustrated Oriental Memoirs of James Forbes (published 1813). Its first volume contains an account of a long stay in Mumbai during the 1770s with a detailed description of the numerous sects and communities that lived in the city.

In these accounts by English authors, the city features as an extended stop in their travel itinerary or is one of the locales for their Indian memoirs. None of these would be considered a book about the city, that is, an urban biography. It was a book in an Indian language that would claim this distinction.

“A view of Bombay, from Malabar Hill”, from the illustrations to James Forbes’s ‘Oriental Memoirs’, via the Internet Archive.

By the year 1800, Persian had been the diplomatic language of India for a few centuries. Most of the Indian upper classes who were involved in administration and law were proficient in it. And so were numerous high ranking officials of the East India Company.

For instance, in this period, most governors of the Bombay Presidency – Jonathon Duncan (1795-1811), Mountstuart Elphinstone (1819-1827), and John Malcolm (1827-1830) – were well-versed in Persian. The Bombay Government maintained an Office of the Persian Translator that functioned as a diplomatic office dealing with Indian princes.

Mumbai had other connections with the language. The Parsis, gradually emerging as one of the dominant communities of the city, were originally from Iran. Though Gujarati was their primary language, there was increased interest in Persian as links with their motherland were strengthened in the late 18th century. Modern Persian, which had evolved from the language in which Zoroastrian religious texts had been composed, afforded the Parsis a means to access their cultural and religious history.

Mumbai had also become the focal point of the thriving Indo-Persian trade by this time and was the first port of call for most Persians arriving in India by the sea route. Mumbai features prominently in travelogues and memoirs written in the early part of the 19th century by Persian businessmen and officials.

Persian had become, for all purposes, an Indian language and the literary output of Indian authors in Persian was voluminous. At the start of the nineteenth century, Indians used it to record histories, write formal and informal letters, compose poetry, and explore religion. It should therefore be no surprise that the first book exclusively devoted to the city of Mumbai was written in the Persian language and published over 200 years ago, in 1817.

For over two centuries, this pioneering urban biography of Mumbai had been lost to historians of the city. Very few copies of the book have survived and even these lay forgotten in libraries, inaccessible because they had been inadequately catalogued.

I first encountered the book as an entry in a catalogue of Persian books held by the British Library, London. The book does not carry the name of the author or the year of publication. There is no mention of the printing press or the location from where it was published. The brave cataloguer had to hazard a guess: London, 1820?

When I eventually laid my hands on the book, I attempted to investigate its antecedents. I compared the book with scores of Persian books published in the early decades of the 19th century in Calcutta and London, the two main centres of Persian printing at that time. I tried to look for similarities in the Persian type used for printing, the page size used for the book, the manner in which the text was laid out on the page, and the paper used to print the book. Only one Persian book was a perfect match. It was titled The Desatir, a book printed at the Courier Press and published in 1818 from Mumbai.

The Courier Press derived its name from the Bombay Courier, a weekly newspaper that had been in existence from 1792. As luck would have it, the volumes of the Bombay Courier for the years around 1818 have survived. And a perusal of the volumes for 1816 and 1817 confirmed my conjecture.

The Jaan-e-Mumbai (or Jan Munbay, as it was transliterated in the advertisement) was announced as published in the Bombay Courier on July 26, 1817. It was printed at the Courier Press. From the advertisement in the Bombay Courier, Mahomed Ghyasoodeen can be identified as the author of the work. Not only was it the first Persian book to be printed in Mumbai, it was one of the earliest books to be printed in the city in any Indian language.

Announcement of publication of ‘Jaan-e-Mumbai’ (Bombay Courier, 26 July 1817).

Jaan-e-Mumbai or The Soul of Bombay was described by its author as “an account of the present state of Bombay, its buildings, populations, trade, &c. together with a succinct history from the transfer of the island by the Portuguese in the time of Charles the 2d to the present day”. The book was first advertised in the Bombay Courier (August 17, 1816).

“Mahomed Ghyas-ud-deen, a respectable and learned Inhabitant of Bombay, has now in the Press, by Subscription, a description of the Town and Island of Bombay, in the Persian Language, giving a succinct account of every remarkable place, both public and private; and everything connected with its topographical nature.

“The work will be written in a pure and easy style, and while it gives Geographical knowledge, will assist the Persian Student; and it is presumed, will not be deemed in that respect unworthy the attention of the learned.

“The price of Subscription will be only 5 Rupees.

“The merit of this curious and interesting work, might justly demand a higher valuation, were the Editor actuated by other motives; but he is solely induced to publish this, through the desire of contributing his small share of labour, to the service of the Public, and to disseminate knowledge in general, a duty incumbent on every one within his respective sphere …

“The book was priced at a hefty Rs 6, a figure that could be estimated as the monthly income of the average Mumbai resident of those days. A discount of Re 1 was available to subscribers who expressed their interest in buying the book prior to its publication.”

Title page of ‘Jaan-e-Mumbai’ (Mumbai, 1817).

Jaan-e-Mumbai is a slim typographical work of 87 pages. The text in each page is laid out like in a Persian manuscript with fifteen lines to a page. The text is set in a single continuous block with no chapters, no section headings, and indeed, no paragraphs. No punctuation marks are used but phrases are separated by a variety of fleurons, floral ornamental characters that are set along with the text. The Persian type used to print the book is a hodgepodge of characters from at least two different fonts. It is the same one that was used by the Courier Press to print Persian advertisements in the Bombay Courier.

The account, written in 1816 (Hijri 1231) during the governorship of Sir Evan Nepean, begins, after the usual invocations, with a description of “Mumbai, the name of the city and the homonymous port and the homonymous island, located about 19 degrees north of the equator on the shores of the Arabian Sea, in the Konkan region of the heaven-like land of Hindustan”. It celebrates the diversity of the city by likening it to “an exquisite fragrance, made by mixing the essences of a multitude of flowers from numerous gardens”.

After describing the Fort of Mumbai and its various gates, Mahomed Ghyasoodeen takes the reader around the numerous suburbs without the Fort: Mazagaon, Byculla, Matunga, Sewri, Parel, Sion, Mahim, Worli, Breach Candy, Mahalaxmi, Walkeshwar and Girgaum. He also describes the various government offices, their functions and gives the name of the civil servants. He lists the two printing presses in the city: the Courier Press managed by Richard Woodhouse, the editor of the Bombay Courier and the Gazette Press run by Edward William Hunt, the editor of the Bombay Gazette. He seems to have missed out Furdoojee Murzban’s printing press that had been set up in 1812 to print Gujarati books.

Mahomed Ghyasoodeen goes on to describe the population of Mumbai as consisting of a mix of nationalities and religions: the English, Portuguese, Dutch, Armenian, Greek, Chinese, Parsis, Hindus and Muslims. Among the Hindus, he identifies the Brahmin, Vaniya, Gosavi, Bhatia, Prabhu, Shenoy, Agri, Koli, Kunbi, Kamati, Lohar, and Dhed communities. He also gives a detailed account of the traditional occupations pursued by each caste.

Mahomed Ghyasoodeen provides elaborate information on the Muslim inhabitants of the city. He identifies the various trades in which Muslims are employed in the city. He classifies them by their geographical antecedents: Arabi, Turki, Irani, Turani, Sindi, Hindi, Kabuli, Kandhari, Punjabi, Lahori, Kashmiri, Multani, Bangali, Madrasi, Malabari, Dakhni, Gujarati, Bagdadi, Basravi, Muscati, and lastly, Kokni, who asserted that they were the first Muslim settlers of the island. He takes especial note of the leading families of the Mumbai Kokni Musalman community: Jitekar, Murgay, Rogay, Purkar, Khatib, Nalkhanday, and Mehry.

While discussing the leading business establishments in Mumbai, besides European firms like Forbes & Co and Remington, Crawford & Co, he lists Mohammad Ali Khan Shustari and Sheikh Abdullah ba Saud.

The description of religious practices is an important part of Jaan-e-Mumbai. The mourning rituals of Muharram are described in detail and so are the festivities during Ramzan. The book provides the earliest information on the dargahs of Mumbai.

Starting with the dargah of Makhdoom Ali Mahaimi (and its pearl-blue domed ceiling) in Mahim, readers can go on a whistle-stop tour of the religious sites of the city: Sheikh Misri at Sewri; Sayyid Badruddin at Bhendi Bazar; Syed Nizamuddin and Syed Mahiuddin at Umarkhadi; Syed Aashiq Shah at Dongri; Syed Hussain Idrus at Saat Tad; Syed Hisamuddin at Don Tad; Pedro Shah on the Maidan; Bismillah Shah by the ramparts of the Fort; Shah Dawul at Kumbharwada; two sites for Shah Madar (Don Tad and Bhendi Bazar); and, Shah Hassan Gazati near the Light House at Colaba. These institutions have stood the test of time and continue to be a place of resort for all the communities of the city.

How did Mahomed Ghyasoodeen come to write Jaan-e-Mumbai? And who were its readers? The literary genre of the urban biography – keeping the city in focus, combining elements of the gazetteer with subjects like history, geography, and culture – was relatively new and did not have precedents in any Indian language.

The initial list of 30 subscribers to the book included Europeans, Muslims and Parsis. At the head of the list was William Erskine, one of the most erudite men then resident in Mumbai and the secretary of the Literary Society of Bombay, who subscribed for three copies. There were civil servants employed by the East India Company such as James Farish and Stephen Babington.

Subscriptions for Jaan-e-Mumbai (Bombay Courier, 17 August 1816)

Amongst the Parsis were Persian scholars (Mulla Feroze and Furdoonjee Murzban) and businessmen (Cursetjee Manockjee, Kaikhusro Sorabjee and Ruttonjee Bomonjee). The Persian expatriate community of Mumbai was represented by the prominent trader of the Shustari family, Mohammed Ali Khan, who subscribed three copies. The initial list of subscribers contains the names of numerous Kokni Musalmans including businessmen like Sherfoodin Arye and Sadooden Shackally Coor and religious authorities like Cajee Goolam Hoosain and Cajee Najmoodeen.

Mahomed Ghyasoodeen would have hoped that in the year that elapsed between the first advertisement for the book and the announcement of its publication, the list of subscribers would have expanded to at least 100. Printing using types, especially in non-English languages, was an expensive proposition and a print run of 300 copies would have been necessary to break even.

Who was Mahomed Ghyasoodeen, the author of Jaan-e-Mumbai? Was he the same Mahomed Ghyasoodeen who, in 1824, proposed the first Urdu newspaper, Moombay ka Hurkara, as “a work of interesting reference, and value to the Gentlemen of the Honorable Company’s Civil, Military and Marine Services?” Or was he the Mahomed Ghyasoodeen who is described as “Expounder of Mahomedan Law” in the Bombay Calendar and Almanac for 1843. Given that all these roles called for scholarship and literary flair, it is likely that it is the same person.

After the advent of lithography, Mumbai emerged as a centre for Persian printing and journalism from the late 1820s. A dozen Persian newspapers and over 50 books were published from the city in the next four decades.

The advent of lithography provided a fillip to printing in Persian and many Persian classics were printed in exquisite editions in Mumbai. As Persian printing moved from typography to lithography, Jaan-e-Mumbai became a forgotten text. Nevertheless, it is the prototype for the numerous biographies of Mumbai which continue to be written 200 years after Jaan-e-Mumbai.

This is a revised version of an essay which first appeared in PrintWeek India (March 2018).