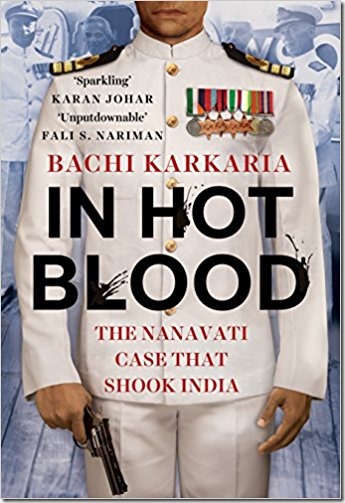

Sticky Towels and a Newspaper with an Agenda: Bachi Karkaria’s New Book Brings Alive the Nanavati Murder Case Madness

Bachi Karkaria’s new book on the infamous Nanavati murder case of 1959 should be a textbook for millennials to let them know they didn’t invent anything — sex, viral marketing and most fascinatingly, trial by media.

by Maya Palit, theladiesfinger.com

May 8th 2017

Sylvia and Kawas Nanavati, shortly after they got married in 1949. Photo Credit: Juggernaut Books

Let’s begin with a vishesh tippani about the subject of Karkaria’s In Hot Blood. On 27 April 1959, Nanavati, a Parsi naval commander coolly rocked up with a revolver to his wife Sylvia’s Sindhi lover Prem Ahuja, and shot him in his Mumbai apartment. Why are we saying Parsi, Sindhi in this uncool way? We want to say “hang on” but that brings us to another thing that hung on.

Despite this jaw-dropping display of capitalism, perhaps the most fascinating historical lesson in this book is its tracing of what was possibly modern India’s first trial by media.

At the heart of the book is the sensational coverage of the murder by one newspaper with a white-hot reputation and a red-hot agenda. Blitz — India’s most-read weekly tabloid at the time, which was started in 1941 — manipulated representation of the case, driven by an almost manic allegiance to clearing Nanavati’s name.

‘Trial by media’ is by now a well-worn phrase to describe the countless ways that the media impacts public perception of a court case — think the Jessica Lal murder case, the blatant lies reported by the The Pioneer prior to Afzal Guru’s hanging, or more recently, the airing of doctored evidence of Kanhaiya Kumar. But what Karkaria points out as different about this case is that it was single-mindedly focussed on defending the accused with a ferocious amount of dedication.

Kawas, Sylvia and their daughter Tannaz (c. 1955)

A man kills his wife’s lover, and then goes to a police station to confess his crime. How do you get him off the hook and all the way to Canada after he’s been sentenced to life imprisonment by a high court? This is not an academic question. Nanavati (accompanied by Sylvia and their children) fled to Canada in 1961, after being pardoned by none other than Governor Vijaylakshmi Pandit. By getting his numerous allies to rally around, making him look like a wronged hero, and tainting the character of the victim, of course. And the editor of Blitz, a Parsi gentleman named Russi Karanjia, was a formidable ally.

Karkaria depicts Karanjia as a ‘masterful conductor’, requesting readers to sign a letter of support to the Governor who suspended Nanavati’s sentence, organising mercy petitions and events to show Parsi solidarity for Nanavati. In one such event, he held a garlanded photograph of Nanavati and shouted, with a show-biz style yodel, “The Struggle Must Go On.” (This veritable mastermind knew just how well sensation sold, and would later tell off his well-meaning deputy editor P Sainath for removing pin-ups of women from Blitz and emulating the Vatican Gazette.) But the alliance to Nanavati was also overwhelmingly obvious in Blitz’s reportage of the case and the court proceedings.

More history? It was India’s last case in which a jury sat on a trial. The jury was made up of two Parsis, two Christians and five Hindus.

Although Blitz did not explicitly refer to the ethnic divide between Parsis and Sindhis in its coverage, it focussed instead on painting a stellar image of Nanavati and pitting him against his dead opponent. This included bizarre gimmicks like commissioning a palmist-astrologer to predict Nanavati’s future, but also the always reliable rhetoric of the Mark Antony school (“For Nanavati is an honourable man”). It placed a strong emphasis on Nanavati’s upstanding patriotic look and white naval uniform (his valour during World War II had been applauded by Lord Mountbatten, claimed Blitz), and his stature as a benevolent family man. Sylvia, meanwhile, was portrayed as helpless, blue-eyed, and remorseful.

From left to right: Sylvia Nanavati, Lt Commander John Pereira, Lt Commander Kawas Nanavati and Joyce Pereira at the Pigalle Club in Piccadilly in London (1952).

Blitz was also hard at work dragging Ahuja’s reputation in the dirt: it insisted he was a rich entitled man (which he was) and an alcoholic, it published his salacious love letters from Sylvia and bizarre notes from women claiming that they felt possessed around Ahuja. Most hilariously, when a police witness mounted Ahuja’s skullcap (a piece of evidence) onto a dummy skull, Blitz’s report described the skull as ‘grinning sinisterly’.

Kawas Nanavati as a midshipman in the UK (1942-43)

Blitz also used the oldest tricks in the book — headlines and visuals — to captivate and sway readers. Wouldn’t you be gripped by captions hinting to a story of epic proportions like “The Tragedy of the Eternal Triangle”, “Three Shots that Shook the Nation”, and “Sylvia Nanavati tells her Story of LOVE and TORTURE”? Blitz was the baap of clickbait, but it also knew how to keep it simple, recreating the crime and courtroom scene through strategic photographs, and tugging massively at the public’s heartstrings with a photograph of Nanavati’s son Feroze under the caption ‘Mr. Governor, Give Me Back My Father’.

These details give Karkaria’s racy book a slapstick quality. The nonchalance with which Blitz was brazenly open about its bias, and descriptions of the cheering crowd practically taking over the courtroom, are surreal.

Karkaria’s book isn’t the first time the Blitz coverage has been examined thoroughly: last year the film Rustom did the same, and previously academics like Jamia lecturer Sabeena Gadhioke and Prakash have underscored Blitz’s populist appeal and single-minded focus on Nanavati’s moral high ground. But Karkaria’s close retelling of Blitz’s passionate defence manages to communicate with a great deal of energy how weekly tabloids turned a relatively banal crime of passion into a polarising force and a national battleground.

In case you’re wondering, Blitz did not reserve its verve exclusively for Nanavati at that time. It reported extensively on other scandals, fabulous rumours of Western plots against India, and political developments like India and China’s border dispute. But turning Nanavati into a ‘cause célèbre’, confirms historian Gyan Prakash, was its ‘mission’.

Karanjia might have been evangelical about his undertaking, but Karkaria hits home in her book that you’d be hard pressed looking for a newspaper without a bias in that period. Karanjia had an arch-rival named DF Karaka, who ran The Current, another weekly which was politically and in every other way, opposed to Blitz. It took the stance that Nanavati was in the wrong. Because they were all about the facts? Nope.

The Current’s primary bone to pick with Blitz had to do with the latter’s pro-Nehru and secular stance, and Karaka took brutal jabs at Karanjia (his tirades like “Sweat it out, chum. Your future now lies in lavatory journalism” might not pass muster in our relatively PC world: think Arnab Goswami dropping ever-so-subtle hints about an American citizen running an Indian media site). Between these rival weeklies, as startling as it might seem to us habitual dissers, perhaps what Prakash informs us is true: ‘sober and impartial dailies like The Times of India’ would have been the ones to peruse at the time.

Kawas Nanavati (extreme left) with friends in England.

Not to say that we are rolling in the laps of non-biased news sources today, especially in the era of rapidly disseminated fake news. But at least the influence of media on court cases is occasionally debated — although courts are temperamental about this too. (For instance, the courts objected to the screening of India’s Daughter because it could influence judges, but not Zee TV’s docudrama December 13, a grossly misleading recreation of the attack on the Indian parliament that called itself “truth based on police chargesheets”).

So plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? No no, nothing about French memes, millennial friends, do not panic. Just that more things change, more they remain the same.

Co-published with Firstpost. All images via Juggernaut Books.