‘The Bicycle Diaries’ details how 12 cyclists set out as global explorers from 1923 to 1942

Last November, tired of being cooped up at home, travel enthusiasts Bakcen George, Allwyn Joseph and Ratish Bhalerao decided to ‘work from cycle’. Carrying their devices and basic necessities, the trio cycled from Mumbai to Kanyakumari — a journey of 1,687 km that took over a month — while meeting their daily work targets. An impressive feat, but not without precedent.

Article by Aparna Narrain | The Hindu

Nearly a century ago, between 1923 and 1942, 12 Parsi men pedalled across the world on their fixed-gear push bikes, traversing the Amazon forest, Sahara Desert, Persia, Korea, Europe and America, witnessing historic events and meeting people who would shape history in the years to come.

In 1923, the Super Six — Adi B Hakim, Gustad G Hathiram, Jal P Bapasola, Keki D Pochkhanawala, Nariman B Kapadia and Rustom B Bhumgara — set off from Bombay on the first-ever expedition by Indian cyclists. However, only Hakim, Bapasola and Bhumgara completed their journey over four-and-a-half years (the others called it off midway for personal reasons).

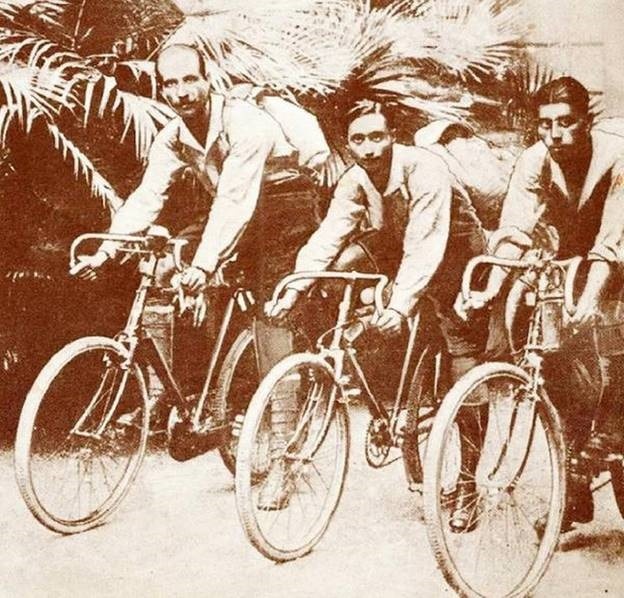

In 1924, Framroze Davar cycled more than 9,000 km by himself, for nearly 10 months, before meeting a young rider, Gustav Sztavjanik in Vienna, who joined him on his expedition. Cyclists Keki J Kharas, Rustam D Ghandhi and Rutton D Shroff rode from Bombay in 1933, while Jamshed Mody and Manek Vajifdar each began their solo journeys in 1934.

Savia Viegas and Anoop Babani

These epic adventures have been painstakingly compiled by former journalist Anoop Babani and writer-painter Savia Viegas in their new book, The Bicycle Diaries, which will release tomorrow. Avid cyclists themselves (“we try to cycle at least six times a week”), Babani says the couple caught the bug in their 60s after moving to Goa from Mumbai in 2005.

Why did they do it?

- “The Parsi community was the closest to the British. If you look at the first entrepreneurs, they were the Parsis. Because of this proximity, they were into many of the allied things that the British did in India. For example, they were great gymnasts. This [cycling expeditions] was a kind of endurance test that they gave themselves,” says Viegas. “They were also doing it for Mother India. From 1905 to 1920, the idea that we could perhaps think of an India [free from the British] was becoming concrete.” Other factors also spurred interest, such as the introduction of the Kodak camera which used film instead of glass plates. “Many Europeans were coming to India to give lectures about their journeys through India. So the imaginations of these boys were fired as to how they could conquer the world on a cycle,” she says.

He learned about the cyclists by chance, after he suffered a fall in 2017 that forced him to keep his feet off the pedal for three months. “We were reading about the Super Six when we found that [Hakim, Bapasola and Bhumgara] had written a book, With Cyclists Round the World. It mentioned Davar [whose journey the couple found the most interesting], and, following that, we learnt about the third journey. By then we had started contacting their grandchildren, grandnephews, friends and neighbours for more information,” says Babani, who curated a photo exhibition on the cyclists, Our Saddles, Our Butts, Their World, in 2018 (Goa) and 2019 (Mumbai). “After reading about the exhibitions in Parsi journals, the daughters of Mody and Vajifdar [who live abroad] wrote to us about their fathers being cyclists too.”

By then they had gathered so much material that they felt “the best thing would be to honour these journeys by compiling them in a book”. Says Viegas, “India doesn’t have a sense of history the way the world does, where every little event that is recorded goes to a museum. But these families still had handwritten notes, photos, and their travel paraphernalia.” Surprisingly, Babani learned that the cyclists had not talked much about their journeys. “When they came back, there were no jobs. Many of them returned when the freedom struggle was at its height. Their children told us that their fathers weren’t very happy people. Nobody really cared about their achievements, so they didn’t talk much about their expeditions. So there were less stories than I expected,” he says.

Framroze Davar and Gustav Sztavjanik | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Why would journeys that happened nearly 100 years ago be of interest to young people today? “It has a lot of relevance because sports history is going to become a part of academics,” says Viegas, a former academician. “[It also serves as inspiration] for younger people. These cyclists went through such hardships; they made themselves into some kind of superhuman machines, travelling with cycles that did not have the wherewithal to go through the desert heat, for example [they stuffed it with straw to make the tyres last].”

Moreover, the cycle has been gaining popularity recently — many cities have Bicycle Mayors, cycle lanes have come up in Bengaluru. Additionally, sales went up by 100% between May and September last year, according to the All India Bicycle Manufacturers’ Association. “The cycle is a machine that’s coming back to life. It is street-friendly and can keep the body healthy. It is very important for youngsters to not only learn to ride it but also realise how it has been a vehicle of adventure. There are so many more stories from places like Europe and South America. It is something that should be in the curriculum,” Viegas concludes.