When Hormuz Mahveer Javat was 8, his parents popped an unusual question to the Mississauga boy: “Do you want to become a priest?”

Although he always attended all the religious services and ceremonies in the close-knit Zoroastrian community, it put a lot of weight on the little boy’s tiny shoulders.

Article by Nicholas Keung | The Star

“Priesthood is hereditary in our religion. You can’t become a Zoroastrian priest if there isn’t one in the family in three generations,” explained Javat, now 14, a Grade 9 student at Mississauga’s St. Aloysius Gonzaga Secondary School.

“My grandfather is not a priest. My father is not a priest. If I didn’t do it, it would stop in the family. And we need to be ordained before puberty.”

For the next four years, Javat spent every Sunday learning about his religion’s rituals, from weddings to funerals, initiation, studying Zend Avesta (its Bible), and memorizing and reciting prayers — in Avesta, the ancient language of the prophets.

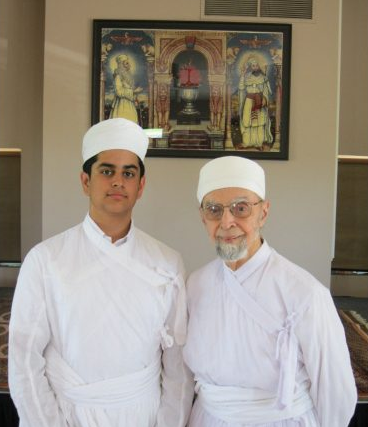

And in 2012, after a 23-day “purification” at the Vatcha Gandhi Agiary (temple) in Mumbai, where he couldn’t have any body contact with anyone, Javat was ordained a junior priest and now can use the Ervad title under his name.

Worldwide there are fewer than 150,000 Zoroastrians, most of them living in Mumbai and some 10,000 in Canada, half of those in Ontario, said Percy Dastur, president of the foundation.

Dating back to 6 BC in what is now Iran, the religious order was persecuted in the 12th century and some members fled to India. The community has been in Canada for more than five decades. The Zoroastrian Society of Ontario was established in Scarborough in the 1970s.

In the early 2000s, with the shift of its membership to the west end of the GTA, the Zoroastrian centre was opened on a 10-acre plot in Oakville. Just three years ago, the foundation began the groundwork to build a consecrated temple, a first in North America.

Although the $3-million, 6,000-square-foot temple is still in the planning stage, Phil Sidhwa, chair of the project’s advisory committee, said the community hopes to start fundraising later this year and built it by 2019.

“The intent is to build a consecrated place of worship for our future generations so we can continue our heritage and culture,” said Sidhwa, 57, who was born in Pakistan, grew up in Tanzania and moved to Canada in 1972.

Sidhwa said the temple has to be anchored with a consecrated fire that is collected from the fires of the households of a soldier, an artisan, a priest and a farmer. The fire will have to be “purified” and burn in the temple 24 hours a day.

“There are temples where the sandalwood fires have been burning for hundreds of years in India,” said Dastur, 44, who moved here from India in 2011 via Dubai.

At 88, Ervad Jehan Bagli will be the most senior priest at the Sunday event. The retired research scientist, originally from Mumbai, said the Zoroastrian religion is not exempt from the sectarian movement and has adapted to survive.

“I’m strongly encouraged seeing young people like Hormuz continue our traditions for the perpetuation of our religion,” he said.