The Demands of the Narrative

The film opens with a close-up of star Rami Malek’s eye, a circlet of pale blue-grey iris clearly visible around a wide black pupil. The actor probably chose to eschew the tinted contact lenses that would have given him Freddie’s chocolate eyes because he found them uncomfortable. But I like to think of this discrepancy in eye color, in retrospect, as an early warning to viewers. To have a chance of enjoying the film, you must accept that it’s not in any sense a faithful account. The directors play fast and loose with chronology, telling only partial truths about Freddie’s life and telling those slant. Events that took place over a number of years—the Live Aid concert; the breakup with his lover Paul Prenter; Freddie’s AIDS diagnosis—are concertinaed into a single sequence, for maximum dramatic effect.

Article by Iona Italia |Aero

But, while film critics and hard-core Queen fans have mostly disliked the movie for these reasons, it’s been hugely popular among audiences: partly because of Malek, a gifted chameleon, whose interpretation of Freddie is exceptionally loving and tender, but mostly because the movie takes the raw material of Freddie’s life and edits and rearranges it into a masterful piece of storytelling. This is not biography: it’s myth. We might most fruitfully see it as one more reinvention of a figure whose life was full of them. Audiences love a good story. And this is a superb one.

Identity As Performance

“How difficult was it to portray someone from a different background?” one interviewer asked Malek. “Very, very difficult,” he answered. “Nowadays the ideal would be for someone of the same nationality [meaning, presumably ethnicity] to play the role.” Some critics have focused on the fact that Freddie was not played by a Parsi actor and his identity as an Indian Parsi, a Zoroastrian, was not sufficiently emphasized in the film. Indeed, his relationship with his parents appears to have been warmer in real life than that portrayed in the movie (his mother has reported that she went to all his early concerts and enjoyed cooking for the band members). But Freddie alluded to his Parsi heritage very seldom in interviews, though in 1985 he told David Wigg: “that’s something inbred, that’s part of me and I’ll always walk around like a Persian popinjay.” This quotation never appears in the film, but the movie does make a visual connection between the photograph of Elizabeth II on the wall of the Bulsara family home—Parsis are famous for an Anglophile fondness for the British royals—and, of course, the name of the band.

But, in general, the film tells a different story and it’s one which we seem to have forgotten in this age of identity politics, in which we so often depict racial heritage as the most important element of a person’s being. The movie provides a salutary reminder that this has not always been the case: that belonging to an ethnic minority used to be less a badge of pride than something to be overcome. But not necessarily in order to conform to some majority culture, not to whitewash, pass or hide one’s roots out of shame. But to transcend such narrow categories as irrelevant.

The film is saturated with imagery of self-transformation. In one early scene, Freddie’s mother shows his girlfriend Mary an album of baby photos, while the singer stands over his parents’ piano and loudly belts out happy birthday to me as he announces that he has changed his name by deed poll, from the traditional Parsi surname of Bulsara to the designation of the messenger of the gods, changing from fixed to quicksilver mobility in a symbolic apotheosis. “Did you know that Freddie was born in Zanzibar?” his mother informs his fellow musicians. But his sister corrects her. Freddie, she archly remarks, was “born in London—at the age of eighteen,” echoing the famous statement of French dramatist, Molière, who also changed his name when he became an artist: “Jean-Baptiste Poquelin was born in Paris. Molière was born in Pézenas.”

Later in the film, the band is shown at a press conference, at which an increasingly disoriented Freddie is bombarded by hostile questions about his background, sexuality and private life. “Your parents are conservative Zoroastrians. What do they think about your lifestyle?” one journalist asks pointedly. “My parents died in a fiery wreck,” Freddie ad libs theatrically. On a literal level this is false, of course. But there is a symbolic truth to the dramatic fiction of the parents consumed by flames. A disproportionate number of classic novels depict protagonists who have been orphaned or whose parents are so self-absorbed or negligent as to have effectively abdicated their role. You won’t have many interesting adventures or be able to get up to any exciting mischief if your parents are watching over you. Nor can you create worthwhile art if you allow yourself to be bounded by their expectations.

In these days of identity politics, being part of a minority ethnic group is often fetishized, not least by those who are part of it. Theories about staying in your lane and ideas that truth is informed by lived experience suggest that each person’s vision of the world is heavily dependent on where he or she is from. Your parentage is your fate: coloring every aspect of your experience, providing a lens through which to see the world. As such, it is a barrier which prevents us from ever truly communicating our experiences, except to those who share our narrow origins. But, rather than recognizing this as a handicap, we valorize it.

One symptom of this is the way in which younger people from ethnic minorities are concerned about cultural appropriation. They don’t want people from the majority culture borrowing their culture’s dress, for example. The anger in some circles over the white teenager wearing cheongsam at her school prom, over pale-skinned pop stars in dreadlocks or bindis, the museum visitors trying out kimono, the vitriol directed at Erika and Nicholas Christakis, for suggesting that students might freely choose how to dress for Halloween—all of this results from a worldview in which how we present ourselves must authentically reflect our heritage.

This ethos is inimical to a performer like Freddie. The glam rock artists with whom the boomer generation grew up rebelled against their roots, rejected conformity to any stereotype—chosen or imposed—and constantly reinvented themselves. The frontman of a glam rock band is his own canvas, his own creation. When we talk about David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust phase or his Heroes phase, we’re not describing simply styles of music. Dress, makeup, gestures, movements, hairstyles: these are all part of the artwork. Identity here isn’t something passively inherited, some birthright fenced about with boundaries to prevent others from trespassing. An artist of this kind cannot be daunted by prohibitions against cultural appropriation: he or she should seize upon anything that serves the purpose of self-expression. Every aspect of human culture should be up for grabs. The local is there to be transcended—even the planetary, as a rocket man, as Major Tom far above the world, as a supersonic Mr. Fahrenheit accelerating up to escape velocity.

We can see a tiny example of this in one of the film’s early scenes, when Freddie, at the iconic London shop Biba, asks Mary if she has a pair of trousers in his size. “This is the women’s section,” she tells him, “so I don’t really know.” But then, after a pause, she adds, “But I don’t think it should matter, do you?” The scene then cuts to her surprising Freddie in the dressing room—“are you even allowed to be in here?” he asks—with a pencil-thin silk scarf to match his outfit and kohl to rim his eyes. We are tolerant of this kind of playful self-invention when it comes to gender. Male performers often appear androgynous or feminine in their self-presentation for obvious reasons: there are more prohibitions and taboos around male dress than female. The sartorial codes of modern masculinity are defined in terms of negatives: men don’t wear skirts or women’s slacks or eyeliner. Those restrictions are, to the artist, a challenge to be overcome. But we are far less forgiving of the overstepping of racial boundaries. When Rebecca Tuval compared transgenderism and transracialism in an article for feminist journal Hypatia, she was widely condemned. Gender expression is a free playground: but racial expression is a privilege, to exercise which we must present the correct bona fides.

One aspect of Freddie’s self-exploration is inevitably tinged with tragedy in the film. Some critics have accused the moviemakers of homophobia because Freddie’s main same-sex relationship portrayed is with the devious, traitorous Paul Prenter, who is cast firmly and explicitly in the role of villain. In a dreamlike sequence, set to the music of “Another One Bites the Dust,” we watch as Paul leads Freddie through the dimly lit, leather-clad world of a gay club, an evil Beatrice to his Dante. Malek’s eyes are alive in this scene. He is a nervous Actaeon, uncertain whether he is hunter or stag, expressing everything through glances alone. Later, when Mary arrives at Freddie and Paul’s rented house in Germany and the camera pans over a table littered with pills and cocaine powder, Freddie tells her that “being human is a condition that sometimes requires a little anesthesia.”

It’s impossible to avoid the associations that come with this portrayal of the rock star lifestyle and its constant search for new sensations, to fill a deep emptiness that cannot be assuaged that way. It’s impossible not to see Prenter as Mephistopheles and the gay sexual promiscuity as a Faustian pact, inevitably ending in premature death. But we need to differentiate here. The gay sex clubs seem sinister to us, not because of our homophobia but because of our foreknowledge. The scenes are pregnant with dramatic irony: we understand the tragic implications of the characters’ actions because we know of the existence of a deadly retrovirus, already quietly multiplying in blood and semen, soon to decimate the gay community. We see the Reaper walking among them. But they, we must remember, did not.

The film never suggests that unhappiness is somehow the reality of being gay or, indeed, of being a rock star. Freddie feels lonely and isolated at this point in the film, trapped in a world in which his sexuality can be expressed only through empty and meaningless hedonism—but, crucially, he is wrong. As Mary points out to him, and as his later relationship with Jim Hutton confirms, in fact, he is loved. The movie will go on to prove it.

The main body of the film is bookended by two references to Freddie as a Paki, the traditional British slur used to refer to South Asians. We see a teenaged Freddie unloading luggage from a plane at Heathrow. He stops to admire a suitcase dotted with stickers from many countries, a symbol of his longing for adventure. “Oi, Paki, stop holding up the line,” he’s told. And, much later, just before the Live Aid scenes which culminate the film, in the kiss-and-tell interview Paul Prenter gives on TV (in real life, this was a print interview with the Sun) we hear Freddie’s former lover describe him as “deep down inside just a scared little Paki boy.” It’s the ultimate betrayal. Not because of the racial insult itself but because of the way it limits and trivializes Freddie. To label is to dismiss.

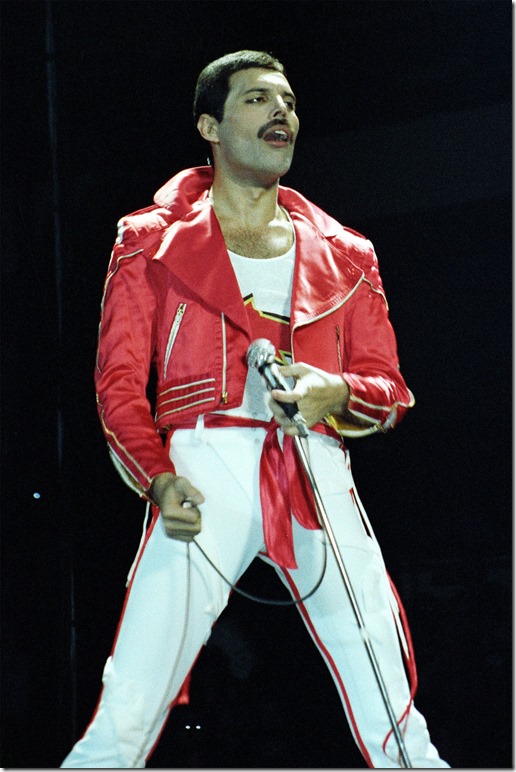

Bohemian Rhapsody ends with a magnificent set piece: Queen’s twenty-minute gig at Live Aid in Wembley Stadium. Malek is outstanding in this, inhabiting Freddie with spine-chilling accuracy, like someone possessed. Some critics have pointed out some obvious parallels with fascist theatrics: the packed arena, the crowds echoing Freddie’s voice, the unison stomping of feet and clapping of hands, the personality cult centered around the charismatic, mustachioed leader. But this is not fascism, though it draws upon the same human instinct that fascist leaders so often exploit—a Dionysian trance in which each individual feels she can transcend who she is, to become part of a greater whole. In fact, it’s the opposite of fascism. Fascism unites people around a shared identity tied to blood and soil. It appeals to people’s sense that they fit their nation, their race perfectly—whether because they are part of a mythical Aryan race and Germany and its surrounding countries are their natural birthright or because India is the sacred land of their Hindu ancestors and must be freed from foreign interlopers. “We’re four misfits, playing for other misfits,” Freddie tells their agent, John Reid, by contrast, when asked to define the band. It’s precisely this sense of non-belonging, of unplaceability, of outsiderdom that creates the appeal. “The people who feel they don’t belong,” Freddie explains to Reid, “we belong to them.” Categories and labels divide. But the search for an authentic, unique self that is sui generis is, paradoxically, the urge that unites the vast crowd as one.

Aapro Farrokh, Our Parsi Boy

Zoroastrianism was once the state religion of Persia but it was already in decline when, in the eighth century, the country was converted to Islam by the sword. A small group of Zoroastrians crossed the sea and found sanctuary in India, where they settled first in Gujarat and later chiefly in Bombay and became known as Parsis (Parsi describes the ethnicity; Zoroastrianism is the religion). There’s a beautiful origin myth associated with their arrival. Legend has it that the local Indian ruler told them that there was no room to accommodate them, showing them a clay vessel brimming with milk to illustrate how full the region already was. In response, the visitors’ head priest called for sugar and carefully stirred in two spoonfuls until they dissolved. “We will live among you, sweetening your society like the sugar in the milk,” he promised, “we will follow your laws, wear your garments, eat your food, so long as we can practise our religion.” It’s a story of integration, a literal symbolic melting (dissolving) pot.

Freddie was arguably an exile three more times: before his birth, when his parents moved from India to Zanzibar; when he was sent back to India, to St Peter’s boarding school in Panchgani, at the age of around seven; and when his parents were expelled from Zanzibar, along with the other South Asian residents, and came to Britain when Freddie was eighteen.

But, despite our peripatetic history, the rules of membership in the Parsi community are strict. You are a Parsi only if your father was one. You cannot convert to Zoroastrianism. You cannot lay claim to the ethnicity by marriage, adoption or even maternal inheritance. And non-Parsis are excluded from our agiaries (fire temples) and sacred wells, not allowed to live in our baugs (colonies). This tiny ethnic group has more fiercely policed boundaries than most.

It’s especially tempting, then, for me, as a fellow Parsi, to claim some kind of ownership over Freddie, some special connection to him, some esoteric ability to understand, some kind of shared credit for his gifts. But that would be both irrational and narrow minded. The important thing about Freddie was not some arbitrary DNA he shared with a tiny population. The important thing was his appeal to our shared humanity. He can’t be contained within the fenced-off category of Parsis. As Malek puts it, he’s the representative of everyone who resists being categorized: “When you ask him in interviews, he often says I’m just me, darling, I’m me, no boxes, no labels. He’s fucking Freddie Mercury and that’s all that fucking matters.”