The city premiere of Divya Cowasji’s film next month will showcase the best and brightest—and last—of Parsi theatre’s singing stars

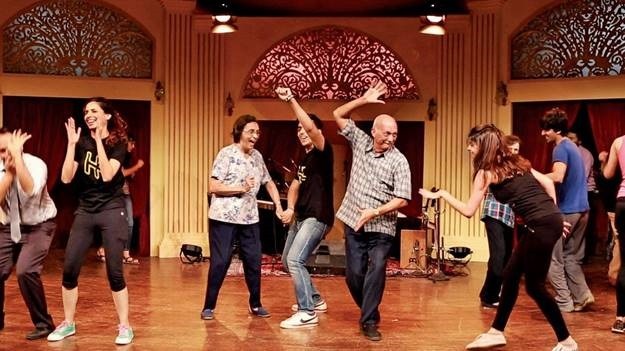

Veteran stars Bomi and Dolly Dotiwala (centre) practising with young dancers and singers

Article by Meher Marfatia | Mid-Day

Sparkling, tender, bittersweet, honest, here’s a film tumbling headfirst into the creative chaos of rehearsals, capturing up close and personal the rumbunctious rapport and superb spirit backstage among Parsi Gujarati theatre’s leading lights. The Show Must Go On, by photographer-filmmaker Divya Cowasji, preserves for posterity their last hurrah.

This second film, after her documentary Qissa-e-Parsi picked up the National Award in 2015, is the inaugural production under the Bhai Bahen Films banner with her cinematographer-filmmaker brother Jall. Nominated for the 2019 ARRI Volker Bahnemann Award for Outstanding Cinematography, he has edited The Show Must Go On.

Rehearsal shot of golden couple, both on and off stage, Ruby & Burjor Patel

From premiering at Film South Asia in Kathmandu last April, to receiving a standing ovation at the International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala, to winning Best Documentary at the Logcinema Theatre on Films Festival in Buenos Aires and being selected to open the International Film Festival of India in Goa, The Show Must Go On has reached far beyond its filmmakers’ expectations. The film will premiere in Bombay with two shows on February 3, at the NCPA’s Godrej Dance Theatre.

“A response that stuck at our Nepal screening was the purity of emotion and relationships coming through. Viewers felt they were watching real life unfold before them,” says Divya Cowasji. Another moment at the Cambridge Film Festival saw a 95-year-old gent from London taking over the post-screening discussion in her absence. “The cinema staff and other audience members took pictures with him because he was a real-life Parsi!”

Dinyar Contractor being directed by Sam Kerawalla

Half a century after they last wowed fans, the ageing icons of Parsi Theatre return to the stage, casting off their walking sticks and wheelchairs for an almost final curtain call. For most of them it has been the last time on the floorboards.

“What has been a nostalgic affair is now ready to be shared with everyone. The fact that such a documentary hasn’t been made—with the last performances of many wonderful actors—makes it a treat to look forward to,” says Sam Kerawalla, director of the productions Laughter in the House 1 and 2, which regaled packed audiences at the NCPA after the publication of this columnist’s book, Laughter in the House: 20th-Century Parsi Theatre. “Despite years of experience, they were willing to accept what I told them. It’s worthwhile for today’s aspirants to observe and learn from taking instructions with no trace of attitude.”

Moti Antia captured in a fun green room moment with Shazneen Acharia

Remembering their mentor, writer-director Adi Marzban, octogenarian Bomi Dotiwala shares, “Laughter in the House is beautiful proof of Adi’s craftsmanship. All of us senior artistes are his products. The Show Must Go On points out how our humble performances attaining stardom, my beloved wife Dolly’s and mine included, are thanks to him.”

Jim Vimadalal, compere for the sell-out shows for both seasons, says, “Laughter in the House 2 was truly memorable, the only show where audiences clapped and howled at every entry even before the act began. That was the aura of the golden oldies and for me a master class in theatre.”

Divya Cowasji shares a laugh with singer Hormuz Ragina

As Shernaz Patel, the daughter of everyone’s most adored star couple Ruby and Burjor Patel, says, “This film is a tiny gem with such a big heart. It intimately captures a rare moment in our Parsi theatre history—one of laughter, creativity and sharing. Theatre is ephemeral. To have a record of these gifted actors before they fade away is priceless.”

Over to the brave creator of The Show Must Go On…

What drew you to filming the making of Laughter in the House 2?

I arrived on the first day of rehearsal with just my DSLR camera and no real plan, to cover a few rehearsals as still images and short videos, handing over the material to those involved as a keepsake. Never dreaming this journey would carry on for over five years.

I started out feeling awkward, a stranger in a room full of people who clearly knew each other intimately. So warm was the energy in that room, by the end of the first day itself, I felt a shift. Day after day, I was unable to put down my camera. Digging myself a metaphorical grave by the end of it with over 100 hours of haphazardly shot footage.

It was apparent this was possibly the last time on stage for most of these actors. I had something special, but got overwhelmed looking at the reams of footage with no storyline. I started and quit innumerable times. There was also the niggling doubt about this interesting anyone outside of the immediate world of the key players.

The decision of this being a film and the direction it ultimately took, was made on the edit table with Jall. It took the better part of a year and a whole lot of trial-and-error piecing together the bits, letting a story unfold itself to us where there wasn’t any obvious tether or cohesion.

Which filmed vignettes were hardest to edit out for Jall?

We killed a lot of darlings, as they say in filmspeak. Jall and I kept struggling to let go much of the masti and shenanigans of the younger lot. We dropped some long gags very dear to us. Most notably, one with Ruby Aunty and Burjor Uncle lamenting the new Tata airline was nothing compared to the earlier one and a skillfully crafted skit around a paidus (funeral) mix-up with exquisite acting by Bomi Uncle and Dolly Aunty. I couldn’t pick a funniest, but the sketch where Jasmin Siganporia presses a seemingly invalid Dinyar Contractor about whether he’s good in bed features significantly, as it was crisp to use in entirety.

Why do you think TSMGO resonates with global audiences despite a tightly niche theme?

Nervous and apprehensive as we were about whether it would appeal to a universal audience unfamiliar with Parsi theatre, the response has been overwhelming. What transcends specificities of context are the overarching human themes. It is first and foremost a film about joy and resilience, not Parsi theatre per se but the people inhabiting this hallowed ground. It doesn’t hurt that the players are loveable in their sincerity, passion, tantrums and eccentricities.

The tender camaraderie between generations of actors and singers is evident.

I was immediately taken by that rare bond, underlined by respect as well as a solid pairing of equals, built on love and genuine friendship. They teased, pranked, sparred, sulked, but consoled one another in times of need. The veterans tried to pass on their rigorous work ethic (and often failed). The kids brought a spark and energy to them that they quite delighted in. One of my favourite scenes is when Sam scolds Shanaya Boyce for not being prepared with words to the songs. Ruby and Dolly stick up for her, getting scolded too. They proceed to not-so-discreetly mouth the words to her, while Sam tests the veracity of their claims.

Poignant moments abound in the everyday: Sam asleep, snoring on some chairs from exhaustion before rehearsals have begun, incorporating Dinyar Uncle’s skits in a wheelchair because he couldn’t walk, Dolly donning a dark wig to appear younger, the sweetest flirtation between Ruby and Burjor as she refuses to reveal her age. The potty humour, the mock rivalry between Hormuz (Ragina) and Jim backstage, the incessant nakhra-naatak both generations revel in, are precious.

The rigour thespians displayed at practices must have been impressive.

Early in rehearsals, something really moved me. There was construction work outside the room, forcing them to tiptoe around piles of rubble and a very long walk to the loo. They constantly faced physical hardships with quiet dignity. They were always first to arrive at rehearsals and stay till the end of gruelling days, with indomitable spirit and great joy to be able to do what they spent their lifetimes loving.

They possess sheer dedication to their craft and utter passion for it. Dinyar Uncle, on occasion, actually called his physiotherapist to the set, refusing to miss a rehearsal. It wasn’t all fun and games, there were heated exchanges. One realised they were sacrificing quite a bit, at times their egos, to be there. And the temerity shown in the face of unspeakable tragedy is nothing short of awe inspiring.

What should Bombay audiences look out for, considering Parsi theatre in India was cradled here?

Showing at NCPA, Bombay feels like bringing the film home, where it belongs. With the luxury of nothing needing to be explained, everything simply understood. Filming the final show, I wouldn’t have been able to fathom the devotion of Parsi viewers towards the senior actors, had I not witnessed it firsthand. I hope they bring that enthusiasm and zeal to this film, so we can celebrate these exceptional talents and human beings, with a love only their ardent, loyal audiences provide.

How do you plan to chart TSMGO’s ideal onward journey?

We’d like as many viewers as possible, so have submitted and been accepted to several global festivals. This April marks a year of the pretty successful festival run, post which we are in talks with an OTT platform for worldwide release. With that we hope our little labour of love will make people everywhere experience a touch of magic of the Parsi stage and its gentlest giants.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com