The Sardar Sorabji Patel Agiary is a vision of calm in the stark concrete jungle that is Nana Peth. Ensconced by trees, a golden Faravahar — the feather-robed angel and the bestknown symbol of Zoroastrianism — stands guard on top of the agiary, which is Gujarati for house of fire. Since non-Parsis are not allowed inside the hallowed chambers of the Parsi fire temple, this is an unprecedented moment for pause and reflection.

Article by Ashwin Khan | Pune Mirror

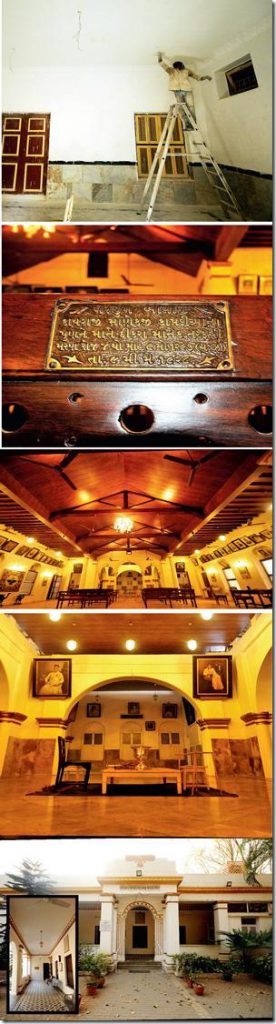

Although the flame is said to burn eternally, the Patel Agiary, now almost two centuries old, has not been impervious to the ravages wrought by time. Just six months ago, its pristine white walls looked a shade darker, and its floor made of solid marble bore stubborn brown stains. The agiary was originally constructed in 1824 by Seth Sorabji Ratanji Patel, a wealthy Parsi sardar — a rank that is equivalent to general — in the Peshwa army and was last renovated almost 60 years ago.

In June 2016, the Sardar Sorabji Ratanji Patel Agiary Trust, began renovation and restoration works and the results are majestic wooden roof trusses that have been polished and burnished until they shone.

“The wooden roof trusses in the congregation hall was covered by a false ceiling made of asbestos. Workers removed the covering so that the trusses could be visible again,” said Ervad Zarir P Bhadha, one of the two priests and fire-keepers of the Patel Agiary. Replastering the ramparts here proved to be a challenge as water had seeped into the walls. The walls have been replastered and painted after the seepage dried. “The doors of the agiary are made of Burma teak. They were covered in seven layers of paint, which were sandpapered before being coated with a special Italian wood finish,” said Jehangir Vakil, one of the trustees, who is helming the restoration project along with Mumbai-based architect Kaiyan Khojeste Mistree.

Classy, minimalistic decor adorns the congregation hall. Hanging lights light up the hallway that is connected to a long verandah with patterned flooring. There is light almost everywhere including the spotless marbled floor that reflects the light of the hanging lamps. Framed pictures of affluent Parsis, who were generous benefactors of the ancient agiary, line the four walls of the hall. The room’s fluted pillars are now freshly painted in white with sombre gold gilding for borders.

The design of the furniture too complements the agiary’s spartan architectural style. Simple wooden benches made in 1928, as a plaque on it informs us, are used by the worshippers while attending prayer sessions for the departed souls of their relatives. Somewhere in the corner of the magnificent congregation hall, a lone antique Victorian wooden chair stands as a testament to time.

Next, Bhadha leads us towards a well inside the agiary’s courtyard, where tortoises and fish swim together. An article on the agiary mentions that it follows an ‘introverted’ cortile plan with a well in the centre (there are two forms of traditional architecture, known among Iranian scholars as “introvert” and “extrovert” architecture). An introvert structure is fashioned to separate one’s private and public life. From the well, we make our way to the fire temple’s office, where the scent of fresh paint is thick in the air. Devoid of any electronic gadgets, the small room includes a mahogany desk, a few wooden chairs, and a well-maintained vintage clock. The old furniture here too has been duly varnished and now looks as good as new. There are at least four ancillary rooms connected to the congregation hall, but only the priests are allowed to enter them.

Well-known architect Snehal Nagarsheth, who has compiled a book on Parsis titled Gaining Ground – Making of a New Homeland, provides insight into the austere architecture of agiaries. She said in an earlier interview, “We realised that consistency is what they were really addressing, and there was an intention to make this their new homeland so they didn’t do something specific architecturally. They did not go ahead and build, like you have the Portuguese, who came and built a style.”

Bhadha and Ervad Jimmy M Udwadia have been tending the holy fire for almost 15 years at the agiary. They are pleased to note that their community is taking an active part in renovating the temple. “Funds have been pouring in gradually,” said Bhadha. The priests tell us that Seth Sorabji Ratanji Patel chose Dastur Jamaspji Edulji of Navsari to be the first high priest of the Parsis in the Deccan region. After the high priest’s death in 1846, his son Dastur Noshirwan Jamaspji took charge. He is said to have rebuilt the agiary during 1867.

The other two fire temples in the city are called the Sir JJ Agiary at Camp and the Anjuman (‘Komra’ Ni) Agiary on Synagogue Street. The latter is said to be frequented by Iranian Zoroastrians. At the last count, 50 fire temples are in Mumbai, 100 in the country, and around 27 in other parts of the world.

█ The doors of the agiary are made of Burma teak. They were covered in seven layers of paint, which were sandpapered before being coated with a special Italian wood finish

— Jehangir Vakil, trustee, Sardar Sorabji Patel Agiary