Ardeshir’s flavoured soda, now christened Ardy’s, still packs nostalgia along with quality ‘old fashioned goodness’ in its glass bottles.

Written by Ruchika Goswamy | Indian Express

The soda company has been a household name in the camp for four generations – from patrons reminiscing of simpler times over an orange soda to the infamous raspberry served chilled at Parsi weddings.

By the late 19th century, the British soldiers had comfortably settled in the ‘Poona Camp’. After a long workday, the soldiers gathered at bars and unwinded with their whisky and soda. Often, whenever bars ran out of soda, the British soldiers would get boisterous, break into brawls and demand more soda water.

Around the same time, Ardeshir Khodadad Irani had arrived in Pune to try his luck. He took notice of the need for soda water and decided that it could be a good business to venture in. By 1884, he started Ardeshir’s soda, one of the earliest soda companies, located two buildings away from the Sharbatwala Chowk in Camp.

The soda company has been a household name in the camp for four generations – from patrons reminiscing of simpler times over an orange soda to the infamous raspberry served chilled at Parsi weddings. 137 years since inception, Ardeshir’s flavoured soda, now christened Ardy’s, still packs nostalgia along with quality ‘old fashioned goodness’ in its glass bottles.

Quenching the soda demand from an old officers barrack

Ardeshir Irani was a money lender by trade from a prominent family in Yazd. After an inadvertent incident in the 1860s in Persia. Ardeshir with just the clothes on his back fled Iran to Quetta (now in Pakistan) and then travelled to Bombay (now Mumbai) in search of work. With no luck, he then came to Pune in the cantonment area which was a happening place at the time.

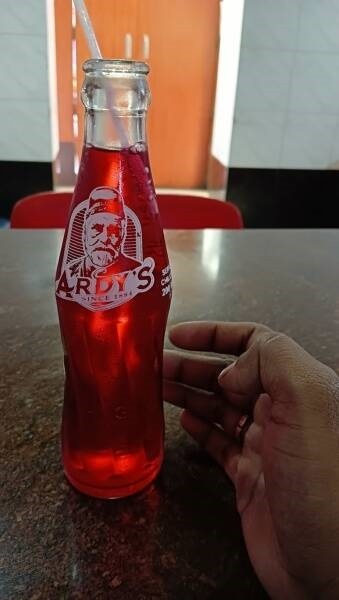

A bottle with rebranded name and logo of the soda.

“My great-grandfather observed that the British soldiers, the army chappies, liked their drink in the evenings. In those days, only one company made soda water called Rogers soda. Rogers either manufactured the soda water locally or packaged soda syphons reached the docks in Bombay. Ardeshir saw that there was a demand for this product and it was something he could do, ” narrates Marzban Irani, the fourth generation Irani running the factory, and the great-grandson of Ardeshir.

A one-man show with neither required machinery nor any knowledge on carbonated water, Ardeshir started small at a dispensary opposite the current factory. He washed and filled the bottles himself. He then fired up charcoal to produce carbon dioxide gas, filtered the gas and manufactured soda. After successfully making carbonated water, he began to supply the soldiers. Soon, Ardeshir was making around ten cases of soda bottles for the British soldiers that helped him get by.

In a matter of two years, Ardeshir’s soda gained much acceptance among the troops and there was a need for a bigger unit. He signed a high purchase deal for the old officers’ barrack then owned by another wealthy Parsi gentleman by the name of Sethna. To improve his production, Ardeshir procured better machinery and machines to wash bottles from countries in Europe.

Old advertisements of the soda drink.

“Around that time he began experimenting with flavoured soda. He had to purchase flavours from popular companies like Bush & Co. and Vimtos, as India did not manufacture locally. The flavoured soda also gained favour among the British. Native residents like the Parsis, Muslims and Brahmins also became patrons of the flavoured drinks,” said Marzban.

A family business to a household name

Ardeshir had six sons and two daughters, among whom the eldest son Framroze could not see eye to eye with his father. Framroze left his father’s company and set up his own soft drink company, Frams, in the late 1920s.

“Framroze, my grandfather had a different vision for his brand. Ardeshir was very content in selling in the cantonment area and did not want to go anywhere. But Framroze, with his drive, took his business around, expanded and sold his products elsewhere. Till the time Ardeshir was alive, both were each other’s competitors,” said Marzban.

After Ardeshir passed away, Framroze handled the day to day while he ventured into the ice-making industry and production of CO2 across India. Frams flourished while Ardeshir remained well-liked among the loyal clientele living near the factory in the camp.

Ardeshir Khodadad Irani

He handed Ardeshir’s to his son Gillan Irani in the 1950s. Gillan, a student of chemistry, studied the technology behind flavours and added more traditional flavours – the orange, the lemon, the raspberry, theeka adrak (spicy ginger) and the ice cream soda. The same formulation is still followed today. “There are many who had their grandfathers and fathers talk about Aredeshir’s to us. It became a household name – people picked it up from the factory shop, took it home and sipped it,” said Marzban.

While the new flavours of raspberry and lemon had loyal patrons, the spicy ginger soda became synonymous with a drink that one had to remedy stomach troubles. “It was 1990, I was fresh out of college and wanted to help out my father. Earlier we delivered our products on bullock carts but that year we shifted to mechanised transportation. In Bhavani Peth, there was a chowk where we would park the vehicle and the residents of the area would come down to buy bottles. One hot summer, an old woman walked up to us and said in Marathi ‘Mala ek Ginger dya, maajhe pot gadbad jhale ahe (give me one ginger, my stomach is bad). She asked me to open the bottle for her and she drank the entire warm bottle of the spicy ginger and exclaimed, now I feel better. That day is burned into my memory,” recollected Marzban.

Staying afloat amid bubbling competition

Between the 1970s to the end of the 1980s consumer tastes and habits witnessed transformations. Parle, with their robust advertising and marketing, added value to their products.

Gillan Irani however was a firm believer that the product’s quality would speak for itself and that talking about it was not needed. “The Cola war between Pepsi and Coke was at its height and each summer the two giant companies broke each other’s bottles. My father thought that if our brand came into their eyes, they would destroy our bottles too and we would go out of business. Hence he did not promote much during this period. When elephants fight, he used to say, it is the grass that suffers,” shared Marzban.

Between the 1970s to the end of the 1980s consumer tastes and habits witnessed transformations. Parle, with their robust advertising and marketing, added value to their products.

As for Frams, it expanded in Mumbai but excise duty barred it from being a regional player. Around 2009-10, Marzban’s cousins, who were by then looking after Frams, thought that pursuing the soft drink industry was not a good proposition and hence they voluntarily shut the company.

Sparkling with the times: From Ardeshir’s soda to Ardy’s

Marzban entered the soda business in 2012 and introduced newer flavours to Ardeshir’s that catered to the extreme Indian palettes – from green apple, peach and pineapple punchier flavours of Jeera Masala and Masala Kala Khatta.

“I was doubtful of toying with something so iconic but how many people know Ardeshir’s? Just the block around the factory. I plan to take it across regions in the country, in Asia Pacific regions. In 2019, we rebranded the flavoured drinks from Ardeshir’s to Ardy’s, a short form. It was to aim for a new target audience. The logo picture is my great grandfather’s. We have tried to retain our tradition with the logo and quality while also changing with time. The plain soda still bears the original full name of Ardeshir,” said Marzban.

On the reason why Ardeshir’s is not found on shelves in the retail market is the returnable glass bottle model, Marzban said, “While we sell out of our factory outlet, have some famous local Irani cafes and Parsi restaurants serve our product, the returnable glass bottle model is what limits us. We can only get back our bottles in for reuse in a 200 kilometres radius,”

While in 2018 Ardeshir and Sons did try to put a PET plant in place, the 2018 state ban on single-use plastic put plans to a standstill. “While glass is the best to store aerated drinks, as it retains the pressure, PET is a wonderful material as well. It can be cut, recycled and made into a brand new bottle. The problem with plastic is the pollution and capricious government policies, as setting up a PET plant is not cheap,”

Marzban informed that to grow Ardeshir, now Ardy’s, reach, they will soon start takeaway glass bottles as well as introduce PET bottles for the easy conveyance of the soft drinks across states, “One of our strengths is our diversity in flavours and we will be working on introducing more, as Indians have a myriad range of tastes. While we bank on our quality, maintained as back in 1884, we will now digitise our logistics to go with the current times,” added Marzban.