Our dear friend Rusi Sorabji writes….

I attach something I wrote about friend, ASPI Engineer*, the 17 years old should go down in the annals of World Aviation better than the likes of Alcock & Brown, Charles Lindbergh, Emelia Earhart, Amy Johnson and to correct the continuous mis-information that is floating around that it was Man Mohan Singh that came first in the Aga Khan Race.

Even as late as last year I saw an article in the Indian press stating Singh came first, but do not find anybody from India refuting that false claim.

I wonder if you’d be interested to carry Aspy’s story below on the anniversary of his prize winning and history making flight, landing in Karachi on May 11th 1930. Let me know.

Some pictures and proof that Aspy won copy of cheque in the name of the winner and covering letter follow in a separately.

Best wishes

Rusi Sorabji.

NB: * the First Parsi Air Marshall of the Indian Air Force, and the Second Indian to hold that post and take the Airforce into the Jet Age.

Ninety-one years ago, on May 11th 1930 a Zoroastrian youngster just 17 years of age achieved a historical landmark

in the annals of AVIATION when he won the “Aga Khan Race” flying solo across three continents from London, U.K. to Karachi, India in an open cockpit World War I era fabric covered biplane. Few of the Parsi community in Sub-continent remember this very young man exploits and the great later in life achievements.

The young lad was named…Aspy Meherwan Irani, but later changed to Engineer – this is his story, a tribute his magnificent obsession with the flying machine.

The Aga Khan Race 1930, was first historical landmark in the annals of Aviation achieved both civil and military in the Sub-Continent -.

Growing up in Delhi in the 1930s, (before the advent, at least in our house, of telephones, radio, TV or cable) the main source of “news” about international events available was, what the parents at the dining table passed on during ‘after dinner talk’. While there was a lot happening elsewhere, it was an era of the airplane and all about flying.

The first flight by man in a flying machine had taken place just 25 years ago and early aviators like, Alcock & Brown, Charles Lindbergh, Emelia Earhart, Amy Johnson were hitting the newspaper headlines on a regular basis with their daring feats. In May 1930, our 17year old hero, Aspy Engineer, also hit the headlines by flying solo from England to Karachi and winning the Aga Khan’s prize. My dad Ruttonshaw and Aspy’s father Meherwan Irani, both worked for the North Western Railway in Karachi.

Dad was so thrilled at the teenager’s achievement and later daring exploits, that we got larger and larger serving of it in the after-dinner stories. Aspy when seven years old, one fine day was fascinated by seeing an aircraft land in the Race Course grounds right opposite his father’s railway bungalow in Hyderabad, Sind. It happened to be the famous English aviators, Alcock & Brown, who made an emergency landing. It was love at first sight for the seven year old and the beginning of a life-long love affair with flying machines, and flying as a profession.

In his unfinished memoir he states “I dreamt nothing else thereafter but aircraft landing on the roof-top of our spacious bungalow.” This dream later carried on through the Billimoria Parsi School years, from where he matriculated. But then having seen the table land plateau above the school in Panchgani, the dream was “of landing on the Panchgani table-mountain’s flat top …”.

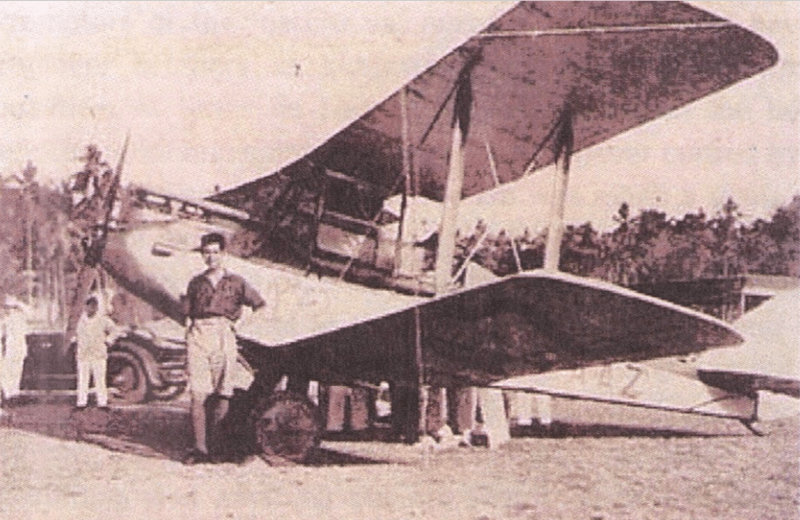

Aspy Engineer with his Farhovar De Haviland Gypsy Moth.

In 1929 Meherwan’ s present for his eldest son’s 17th birthday was a second-hand DE Havilland, Gypsy Moth, bi-plane, which at the time was the most popular aircraft with the Aero Clubs, the Royalty and the High Society in Britain. It was a two seater, open cock-pit, 30ft wing span, wood and fabric structured aircraft with a four cylinder100 hp engine. After quickly obtaining his license from the Karachi Aero Club and flight training of less than three months, Aspy with his friend R N Chawla took off for England on 3rd March 1930 to participate in the Aga Khan Cup, with a Farhovar painted on his aircraft and registered as VT.AAZ.

To popularize and promote aviation in India, His Excellency the Aga Khan had offered a handsome cash prize of Pound Sterling five hundred, for the first Indian to fly solo between the two countries England and India. The flight could be in any direction, from India to England, or in the opposite direction, but it was to be completed within 30 days. It is difficult to comprehend that in less than three months of owning a plane, obtaining a license to fly, the boys were undertaking a flight of 5,000 miles. It was like shooting for the impossible, considering a major portion of the flight was over deserts with little known air strips, scant refueling facilities and involving sea crossings. Besides, it was being undertaken at a time when Radio Communications or Air Traffic Control were unheard off. Under the circumstances, one can have nothing but admiration for the pluck of this teenager and a determined pilot. But, Aspy also firmly believed in his mothers’ dream that he’d come back a winner of the race.

In his excitement to get off to London he did not carry maps or directions beyond Egypt, hoping to collect them in Cairo, which then was an established airport. To make matters more difficult, the Gypsy Moth was a light airplane with rudimentary instrumentation and no communication equipment. The pilot in the open cock-pit was to be on his own, keeping visual topographical contact through unknown skies and under bad weather conditions. Something impossible to do so during sand storms that were common during the time of the year, along the Middle-Eastern countries and the North African coast.

As Aspy writes “we had to sort of smell our way about”.

A better portion of the flight was over nomadic road-less deserts infested with raiding Bedouins. When they crash landed in the desert, one night near Homs in Tunisia and Chawla had walked to town in search of fuel, Aspy actually had a close encounter with a horde of Tunisian bandits.

Runways were no more than flat strips of ground swept clean of rocks, with no proper fuel sources “we were our own navigators, mechanics, refueling staff and what have you, rolled into one. Availability of water, fuel, food or a cup of tea presented quite a problem in many places” until they reached the British air bases at Basra, Bagdad and Amman, wrote Aspy.

With three forced landings and much luck, they made their way across North Africa, Malta, Italy to north of France in 17 days. They missed Paris and landed near the Belgium border. Then misunderstanding the French instruction, they were lost over the North Sea in cold heavy rains. As their fuel was running low and head wind reducing their speed considerably, Aspy spotted a tramp steamer and was able to get directions in ‘sign language’ as they flew low around it. Correcting their course in the direction their unknown benefactor had indicated, they finally struck land in the evening and force landing on a farm. Later they discovered they were in the village of Thetford in Norfolk, quite some distance north from their destination, London. They were met by a very angry farmer, who turned very co-operative once he heard their unbelievable story and taking pity ontheir bedraggled, frozen conditions and their youth, invited them to his house. And just as they were enjoying the “roast beef, Yorkshire pudding and a large tankard of brown ale”, the pressmen arrived to join in the dinner and collect their story. It seems the farmer had phoned Croydon of the arrival of the boys from India and invited the press assembled there for a quick dinner.

Next morning 21st of March 1930 they flew into Croydon at 11am where the Mayor of London and the English press awaited them with garlands.

These were the first Asians or Indians ever to fly from India or the East to England. Two high spirited boys, one 17 and the other not much older. Unlike their American or British contemporaries they had no sponsors, they were on their own helped and financed by Aspy’s father, Meherwan Irani.

Picture of Ram Nath Chawla and Aspy Engineer ( garlanded ) on arrival at Croydon, London, England on 21 March 1930 for the Aga Khan Race.

After the plane was serviced by the manufacturers DeHavilland, Aspy participated in the Aga Khan Race, setting off for Karachi one fine morning on the 25th of April 1930. With meticulous planning and preparation, his flight was uneventful throughout, except that he experienced engine trouble at Benghazi, so did Manmohan Singh. However Aspy with his engineering skills was able to get going to Alexandria, where he met the other Zoroastrian participant in the Race JRD Tata heading for England from Bombay. When Aspy informed JRD of his engine and spark plug problem, JRD offered him a spare set of spark plugs. In return Aspy gave JRD his life belt for the sea-crossing. This saved Aspy several days of waiting at Alexandria for plugs. He later faced severe sandstorms on his flight between Basra and Bagdad, but was able to hop into Karachi at 4:10 pm on the afternoon of 11th May 1930.

Next day the Royal Aero Club, London, cabled, confirming Aspy as the winner. JRD Tata’s flight to England clocked 20 hours over Aspy’s time.

Though Manmohan Singh landed in Karachi earlier than Aspy, he was disqualified as his flight that started in January took much more than the specified 30 days.

Of the three Indians who took part in the Aga Khan Race two were Parsis, Aspy Engineer, 17 yrs from Karachi, and Jehangir R D Tata, 26 yrs. from Bombay, heir to an industrial empire. The third man Mohan Singh, 24yrs was from Rawalpindi, a qualified flyer and an aeronautical engineer, but had bad luck, crashes and injury on his flights from England. The first of his three attempts to fly to India was on 11th January,1930. All the three flew Gypsy Moths.

Aspy’s heroic and record setting flight thrilled people throughout India, but the public celebrations, awards or ticker parades, that greeted his more senior and well financed US contemporaries like, Charles Lindberg, Amelia Earhart on achieving similar feats, were missing. Whereas the US President Calvin Coolidge awarded Lindbergh the Congressional Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Flying Cross for his flight to Europe from America, there was nothing like that in store for Aspy from the Government. The BVS school band, known as the Cowasjee Variawa’s Own, played as he landed. The large crowd that had gathered cheered him. He was garlanded by the Mayor of the Karachi, Jamshed Nusserwanji, congratulated by the Chairman of the Karachi Aero Club and by the President and Secretary of the Karachi Parsi Anjuman.

Next day The Royal Aero Club, London, cabled confirming Aspy as the winner. The Karachi Parsi Institute’s President, Khan Bahadur Kavasji H Katrak held a dinner celebration on the Institutes spacious grounds to congratulate the young boy for this outstanding achievement. At the reception in Karachi, a reporter asked about what he saw in his future. The young man replied, “I would love the chance to serve my country in the Air Force”.

A wish that soon came true.

The Legislative Council of India awarded Aspy Engineer a special prize of Rs10,000.

Sir Frederick Sykes the Governor of Bombay State which then included Karachi, upon learning that Aspy was the winner wanted to honour him with a suitable public reception in Bombay.

Taking off for Bombay, much against the wishes of his mother, Aspy was injured when he crash landed at Bhuj and could not make it to Bombay. Instead, upon recovering he flew in to Panchgani and landed on the rough Table Land plateau, his old School’s playing field, fulfilling a dream and keeping the promise he made to the boys at school and his Principal before he matriculated.

Late Mr. K.T. Satarawalla of Delhi, then a student at the school, remembers how the whole school and the people of Panchgani had gathered to welcome Aspy and how the Governor of Bombay visited the school to present a ‘Big Cup’. This was in addition of being honoured and facilitated by the Principal of the School. Aspy’s son Cyrus Engineer, tells me he has the movie that was taken of the presentation. The very next year Aspy joined the Royal Indian Air Force and was selected for training at the RAF College at Cranwell, England (3rdSeptember 1931 to 14th July 1933).

As the lone Indian in his batch,“Graduating from Cranwell, I won the Groves Memorial Prize for being the best all at Cranwell.” wrote Aspy in his unfinished memoir. He stood first in the Army Cooperative course at Old Sarium. He also won a Caterpillar Badge (with ruby eyes) when he had to bail out from a burning aircraft during aerobatics.

Life in the RIAF

On commissioning from Cranwell, he joined the “A” Flight of No 1 Squadron, of the two squadron Royal Indian Air Force. He was first posted at Drigh Road,Karachi and later to the North Western Frontier Provinces as a flight commander.

“The main equipment of the RIAF, eg. the aircraft we flew were really antiquated. The Westland Wapiti was an ungainly biplane and carried a pilot and rear gunner in open cockpits. We had none of the airbrakes, flaps or even wheel brakes. No R/T communication”, wrote Aspy.

In 1939 Aspy Engineer’s “A” Flight executed 403 hours of relentless operations bombing and strafing Waziristan’s restive tribes.

Once according to my father Ruttonsha, Aspy returned from a sortie with more than a dozen tribal bullet holes in his fabric and wood Westland Wapitis fighter. Waziristan was as dangerous then, as it is now. Kohat and Miranshah were at that time under the domain of the Faqir of Ipi, with sharp shooters carrying long barreled home-made guns, who could shoot at night from the surrounding hills with only the burning end of a cigarette as their target.

Aspy was continuously mentioned in dispatches for bravery in action and in 1942 became the first ‘native officer of the RIAF’ to be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for action in the NWFP. Soon he became the Officer Commanding Kohat. He also briefly saw action in Burma against the Japanese before being posted back to the NWFP. Later towards the end of WWII he gained the rank of Wing Commander.

The start of World War II necessitated the expansion of the RIAF. This found FLt Lt Aspy Engineer on various selection committees. And this is what young Hoshang Patel of Nargol had to say about his meeting Aspy at the job interview. Good conversational English was a prerequisite for joining the RIAF as an Officer. Since Patel was poor in English he was told he may not get in as an Officer.

Without much deliberation Patel asked, if he could join in as an Airman. Flt Lt Engineer who was on the interview board, dissuaded him from joining as an airman saying, “Hoshang, don’t join the ranks, Parsi boys from Bombay can’t take the tough life there”.

Meanwhile a skinny Malayali Corporal came to Aspy for some signatures or something. After the Corporal left, Patel asked, “who is that man?” he was told he is a Corporal in the RIAF. So Patel asked the selectors, “will you ask him to wrestle with me, run 100 yards or a mile race with me? I will beat him in all, and I mean it!”

“So you still insist on joining?” asked Aspy. Patel agreed. “You promise never to blame me?

Because all the Parsi boys who have signed up are blaming me, saying that I promised them heaven”, said Aspy.

Patel who joined the RIAF in the ranks,retired as Wing Commander Hoshang Patel. During my conversation with Wing Cdr Hosang Patel (then 88) in Bombay, in November 2010, slip-of-the-tongue I addressed him as ‘Squadron Leader’. Pat came the loud rejoinder, as if from a senior Englishman, “Wing Commander, to you Sir!”

At the time of Partition and the bifurcation of the old RIAF into IAF and the Pakistani half, found Group Captain Aspy Engineer and his Partition Committee for seconding RAF Officers and Senior NCO’s to staff the Indian Air Force during its early days, the Chairman after a deep breath said, “Engineer, I suggest you go take a cold shower and come back. This is a serious matter and I give you three months before the IAF collapses and then you’ll ask for a larger number of RAF NCO’s”.

Engineer’s response was, “Sir as a matter of fact I had to have a cold shower this morning as the heaters had packed up.”

Both Mukerjee and Engineer were convinced it was the right decision, as IAF had to be Indianised so as to be able to stand on its own feet.

Rapid expansion of the IAF began in 1947 and rapidly became an all-jet Air Force that gave a good account of itself in the war that soon followed over Kashmir. Before long, he was promoted as Air Commodore and given command of No1 Operational Group. Later he took charge of Personnel & Administration at Air Headquarters. During the 1950’s the IAF deputed Aspy on a one year course at the Imperial Defence College, London. On his return he was assigned to various posts and led several missions abroad meeting with heads of States and arranging for the training of pilots and technicians of countries such as Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq and Afghanistan at the same time overseeing the expansion of the IAF to a 64 Squadron force.

When the Hindustan Aircraft Ltd factory was experiencing serious labour trouble, Aspy was appointed its Managing Director (1958-1960). Before long the labour problems were resolved and the factory gainfully embarked on several new projects including the construction of a new engine factory. It was during his short tenure that HAL did pioneering ground work in the development and production of the first jet trainer and the designing of the first indigenous jet fighter. On 1st December 1960, upon the sudden demise of Air Marshal Subroto Mukerjee,Aspy assumed the office of the Chief of Air Staff, Indian Air Force.

Twenty-seven years after commissioning from Cranwell, Aspy Engineer was heading the Air Force of the most populous nation of the Free World. During his tenure as Chief of Air Staff, the Indian Air Force saw action in Goa, and a detachment of Canberra bombers were sent to the Congo where they took part in action against the Katangese.

Aspy the engineer, though he was the Chief of Air Staff took keen personal interest with engineering and modifying the two engine propeller driven C-119 Packet aircraft, by adding a jet engine innovatively mounted on the top of the fuselage. This was to make the C-119 operate from short runways at higher altitude. Air strips carved out of mountains at heights never before heard off anywhere in the world. It was indeed a feather in the IAF cap, when for the first time in the annals of aviation, on 23rd July 1962, a C-119 landed and took-off from an airstrip at 17,000 feet. This created lines of supply for the brave soldiers guarding the country’s frontiers along the very high Himalayan border.

In the 1962 sneak Chinese invasion of India, IAF was unable to provide air support to the brave Indian soldiers at the borders, as the Government did not allow the IAF to deploy combat formations against the Chinese invaders. After the war, Aspy Engineer was responsible in overseeing the expansion of the IAF. Besides setting up new training facilities and infrastructure, this period also saw the induction of the first supersonic fighter, the MIG 21, and the augmentation of the transport and helicopter fleet.

He retired on 31st July 1964. But, that was not the end of the love affair with flying that started when he was seven. He continued to see his younger siblings who were influenced by his remarkable attainments, make history in trying to almost out-perform him.This was one unique family of four gallant aviators and two outstanding musketeers.

More of that at some later date.

Three DFCs in a family? I doubt one can find another example. The DFCs were awarded to Aspy for action in the NWFP, Minoo and Rohinton Engineer for action against the Japanese in Burma in WWII. Nor of two brothers as Air Marshalls, Aspy and younger brother Minoo; one a pioneer and the other the most highly decorated officer for gallantry in the Indian Air Force or in the Indian Armed Forces. After retirement from the Indian Air Force, Air Marshal Engineer served as India’s ambassador to Iran.

In 1990 or so he settled down in Southern California and was a founder member in establishing the California Zoroastrian Center, in Westminster. Later he returned to Bombay where he died on 1st May 2002. The 1930 Aga Khan Cup Race became the first historical landmark in the annals of Indian Aviation, both Civil & Military. The two Zoroastrian Aviators who were the only ones who successfully completed the Race,were later to become the main builders of the Indian Aviation, Aspy the Architect of the Indian Air Force and JRD Tata the Architect & Builder of Civil Aviation in India, starting with the Tata Airlines and then Air India International, what used to be a world class airline, the pride of India.

“Should we forget such an achievement and example set by Aspy for our young?” asked K.T.Satarawala.

The pride of being a Zoroastrian is something that is passed on by parent to child, a parent whose intention is to convey what was the best and most noble in their heritage. As each generation of Zoroastrians dissolve further into the global melting pot, it becomes more urgent and necessary to record and recognize the talents and contributions of our forebears. I feel it is essential for individuals with Zoroastrian background to recognize the contributions of their ancestors and to pass on a sense of Zoroastrian pride to their children and grand-children. My parents did it. I did it, now I leave it to you.

RUSI RUTTONSHA SORABJI.

Acknowledgement: My thanks go to each one, without whose assistance this story would not have been complete:-

Mrs Farida Singh, daughter of Jehangir Engineer

Cyrus Aspy Engineer, for providing pictures,

newspaper cuttings and his father’s story

Bharat-rakshak Samir Chopra

Air Commodore Minoo P. Vania. S.Chakar.& VSM.

Late Air Commodore Minoo Mehta

Late Wing Commander H Patel

Late Sam Pedder, RIAF & Air India

Mehli R Bandrawalla, Indian Air Lines & UN

Statute of Aspy Engineer at Croydon Museum. In honour of his winning the Aga Khan Race. Last seen there by his family about 1990 as also noted on the picture by his family.

You might note he is wearing the leather coat he bought in Cairo.

A picture showing the primitive instrumentation and a joy stick for flight control that was available in 1942, on an almost similar, but 20 year later, more advanced model of a two-seater open cockpit, fabric covered bi-plane. Which had brakes on its wheels. Aspy’s plane did not. The all-important FUEL GUAGE of the old planes were not in the cock-pit that the pilot could keep an eye on. It was outside some 5 feet away, sometimes hanging from the wing downwards, as may be seen in the next picture almost touching my left elbow.

Golden Gate Bridge on the right, rain clouds straight ahead as we approach San Francisco and no umbrellas. There was bright sunshine when we took-off.

That is me getting into the plane flying over the California coast and American Wine country trying to find out what it was like flying like our “hero” in an open cockpit in an almost 70 years old plane, with a 16 inches glass wind screen as the only frontal protection from the 125m.p.h. wind blast hitting your face. It jolted the tele-lens of my tightly gripped camera to its fullest extent, when I tried taking pictures