In the cramped heart of the suburb called Andheri, the MF Cama Athornan Institute was strangely quiet. The institute, founded in 1923 to train Zoroastrian priests, is a large, M-shaped edifice with excellent infrastructure and teachers dedicated to the welfare of their students.

By Samanth Subramanian

At present, those students number precisely four.

One leg of the M has been rented out as office space to an aviation academy. "Have you ever seen a school like this, where there are more teachers than students?" Dastur Firoze Kotwal said with a sigh. Mr Kotwal is a high priest and one of the religion’s greatest scholars. He is also an alumnus of the Cama institute and a former principal there. "It is almost a dying seminary."

The state of the Cama Institute, Mr Kotwal said, mirrors the state of the priesthood in Indian Zoroastrianism. "For every 10 priests who pass away, there isn’t even one to take their place," he said. "Nobody is entering the priesthood anymore."

Much of this shortage stems from the tension between secular and religious studies – between the choice, in front of a young man, of a private-sector job in India’s booming economy and the relatively low-paying, unstable work of a priest.

The first mention of Zoroastrianism dates back to the 5th century BC, making it one of the world’s oldest religions. The Indian Parsis are descendants of Persian Zoroastrians, who, forced into a minority by the advent of Islam, fled to south Asia, in particular, to India’s west coast.

The Parsi community is still concentrated in the western state of Gujarat and in Mumbai. The last Indian census, in 2001, counted 69,601 Parsis in the country – a decline from the 1981 figure of 71,630, and from the 1951 figure of 111,791. A report by the National Commission for Minorities identified low birth rates and migration as causes for the steady drop in India’s Parsi population.

Khushru Panthaky, the principal of the Cama Institute, one of the two Zoroastrian seminaries in Mumbai, called the Parsis a "microscopic minority". So while the number of students aspiring to the priesthood is dwindling in every religion, he said, "the problem is much graver in such a small community", because the death of the clergy will mean the death of the religion.

Until the late 1970s, the Cama Institute offered both secular and religious lessons, but its trustees began to observe seminary graduates drifting away from the priesthood and towards other professions. In reaction, they removed the secular component entirely – and watched, then, as the number of students dropped from nearly 50 into the single digits.

By the time secular studies were reinstituted, roughly a decade ago, it proved too late. The strength of the Cama Institute’s student body has hovered in the low single digits ever since.

One former priest, who asked to remain anonymous, recalled the Cama Institute’s redaction of secular studies as a major mistake. "Who’d want to be illiterate?" he said.

He insisted that he didn’t regret abandoning his training for a job in the insurance industry.

"Would I have got 80,000 rupees [Dh6,400] a month, a car, a holiday home, medical benefits, and a 9-to-5 job as a priest? I wouldn’t. Which is why I don’t want my son to become a priest either, even though he’s studied for it. ‘Tell me you’re not going to practice’, I keep saying to him."

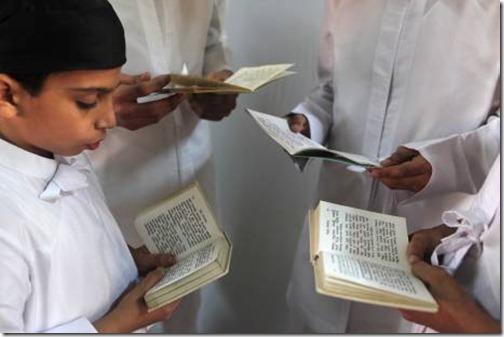

But at the other major Parsi seminary in Mumbai, the Dadar Athornan Institute, the principal, Ramiyar Karanjia, appeared optimistic. His school has 22 students, and its premises seemed distinctly livelier. Students’ chants in Avestan – the ancient Zoroastrian language – filled the building as they pored over their lessons.

Mr Karanjia quickly offered other examples of priests who were, in the true hereditary tradition, initiating their sons into the profession. "It’s true – priesthood may not be the first choice for these youngsters. There aren’t any benefits, and it isn’t a glamorous job," he said. "Until recently, in fact, young priests couldn’t even eat out or go to the movies without exciting comment."

But Mr Karanjia cited a number of schemes initiated by the Athornan Mandal, a welfare body for priests, to supplement the priests’ incomes. One adds 2,000 to 3,000 rupees a month to a young priest’s salary while another offers a purse of 30,000 to 50,000 rupees to priests who complete 40 years of service.

"A full-fledged priest can earn 25,000 rupees a month," Mr Karanjia said. This is, no doubt, a sharp increase from earlier salaries in the clergy. But some priests point out that 25,000 rupees goes only so far in a city like Mumbai, and intelligent, well-educated young men can find jobs with salaries that could be 10 times higher.

The lack of qualified priests has begun to affect the quality of Parsi rituals, said Pirojshah Siddhwa, a teacher at the Cama Institute and a member of the Athornan Mandal’s managing committee. "Sometimes we can’t even find the full complement of 14 priests for a particular ceremony – priests who know every prayer by heart," he said. "So we often have to bring in priests who simply read out the prayers from a book."

Some Parsi temples, in fact, have started to ordain priests who have memorised only a couple of the requisite chapters, rather than the full 72, of the liturgical texts. This abridged course of study takes only a few months, as compared to the orthodox route of six to eight years.

Mr Karanjia suspected this was a bid by the temples to supplement their incomes: performing an initiation can bring in a fee of up to 50,000 rupees. Mr Panthaky, the Cama Institute principal, opposed such "read-only priests".

"Some of the higher-order rituals need both hands. How can a priest read and perform those rituals?"

Mr Siddhwa seemed resigned to this trend, as much as he said it disturbed him.

"Even reading the texts takes a certain expertise, and many of the people ordained this way can’t read at that level," he said.

Then he smiled sadly through his snow-white beard and said that if a priest can read well, it may only be practical to use him. "Perhaps, at this stage, we can’t help it."