What would Charles Forjett make of the colourful characters inhabiting the street off Gowalia Tank Road named for him?

He was a top cop in the days when the term really meant something. Slipping into clever disguises just to bust 19th-century crime rings, he formed night patrols and rallied the city’s first force. Swarthy Charles Forjett blackened his face further, donned desi outfits, spoke local lingo and slunk along streets feeling the pulse of the people.

Article by Meher Marfatia | Mid_Day

The genial hero hardly christened Forjett Street for sporting incognito avatars alone. Volume 1 of the Bombay City Gazetteer describes Forjett (only “Deputy” and “Acting” Commissioner of Police, 1856-64, being Anglo-Indian): “His foresight and extraordinary knowledge of the vernacular saved Bombay from a mutiny of the garrison.” Whatever the veracity of that claim to uncover 1857 “conspiracies”, the desi-at-heart detective would quite enjoy knowing the road he christened thrums in a robust mesh of Maharashtrians, Marwaris, Gujaratis, Muslims and North Indians. With generous numbers of Parsis and Iranis gratified that the street they settled on has always exuded a culinary vibe.

Nilesh Amonkar, seen here with his oldest mechanic Ramesh from Nainital who has been with Sitaram Auto Works for 50 years, feels Forjett Street still retains its basic character. Pic/Ashish Rane

First up is Gowalia Tank Dairy, opened 70 years ago by Ahmad Sahid Vora. His son Ayaz says they supplied milk, dahi, paneer, lassi and, finally, bestselling grilled sandwiches – carb treats so tasty, even fitness guru Mickey Mehta can’t resist them. Past the dairy, Parsi Amelioration Committee Cooking and Confectionery (PAC, now at Tardeo) sold cutlets, wine biscuits and crumble-fresh nankhatai, shortbread Persian chefs learnt kneading from the Dutch docked in Surat. Delbar Mendis shares that her grandmother Jerbai, whose husband Sir Noshirwan Engineer was the first Indian Advocate General, founded PAC in 1938 to groom self-reliant women. Further into Forjett Cross Lane, Rajasthani Mahila Mandal has empowered women since 1956. My eyes watch a dozen of them cleanly pound spices and roll papads. My nose leads to their shop, aromatic waves of these masalas, sherbets and pickles wafting strong. “Our range is better than home-made,” Mandal treasurer Uma Seksaria swears, impossibly perfect as that sounds. With product manufacture, sewing and computer classes, Hindi and English schools, the institution holds medical clinics and civic awareness programmes.

Prochi Bhada at her 40-year-old beauty parlour believes the selfie age has made customers more conscious of frequently changing hair styles and colour. Pic/Atul Kamble

At Fakhera Charitable Trust in Crown Mansion smiling seamstresses handcraft Bohra ridas with fastidious finesse. Layering ghagra skirts and pardi hooded capes with appliqué, crochet and cross-stitch borders, the ladies lace apt variations for customers who play tennis, ride a horse or appear in court dressed in black and white ensembles. “Fakhera – tree that blossoms – brings hope and confidence to several women, including victims of domestic torture,” says Tasneem Hasanali, associated for 35 years with the 1960s-established store. Two floors up the same building, more nimble-fingered artistry created tender threads on purple, red and black silk. Widowed in 1987, Naju Daver converted her hobby of embroidering gaara sarees into a profession her daughter Farzeen nurtures. This intricate textile tradition Parsis imbibed from Chinese merchants, presents pastoral patterns paired in female and male motifs, suggesting harmony and fertility.

Charles Forjett, who gave his name to Forjett Street, was the first to formally organise a police force for Bombay in the latter 19th century Illustration/Ravi Jadhav

In the reign of skin spas and destination weddings, Prochi Bhada resolutely hangs on to her simple Piroja House salon, soon completing 40 years. Loyalists like Saby and Geeta have pampered clients of Prochi’s Beauty Parlour over 30 years. The bridal make-up specialist says, “For 20 years work was so great, I had no time to eat lunch during festivals like Diwali.” Bhada’s neighbour Bapsy Patel recollects Apsara egg shop closed after the 1993 riots compelled some Muslim shopkeepers to leave. Bang below, on Piroja House’s ground floor, Nergish Bagwalla packed provisions in paper and string at Hygiean Stores not easily found elsewhere. Like the fine rava mixed into maleedo, ultimate sin Parsi shira. The shop shut in 2007 after a creditable innings – her father Sorabji had bought it in 1949. Right across, Forjett House, among the street’s earliest 1900s structures, predates the late 1920s Banaji Buildings. Designed by Parsi and British architects, the Classical Revivalist style with Indian elements renders it still striking. The brothers Khan, of Well Known Watch House, a tick away, have occupied the upper level of Forjett House from 1955 when their father Mohammed Anwar Khan of Bhopal secured rooms. Horology meeting history, between cuckoo clock chimes, Ikram, Imran and Aftab share some building facts and Rahat walks me through. Admiring vintage meter boxes and mosaic tiled landings, we ascend the spiral stairway to the flag-post capping a corner dome. The handsome building reveals different stained-glass panels above each veranda.

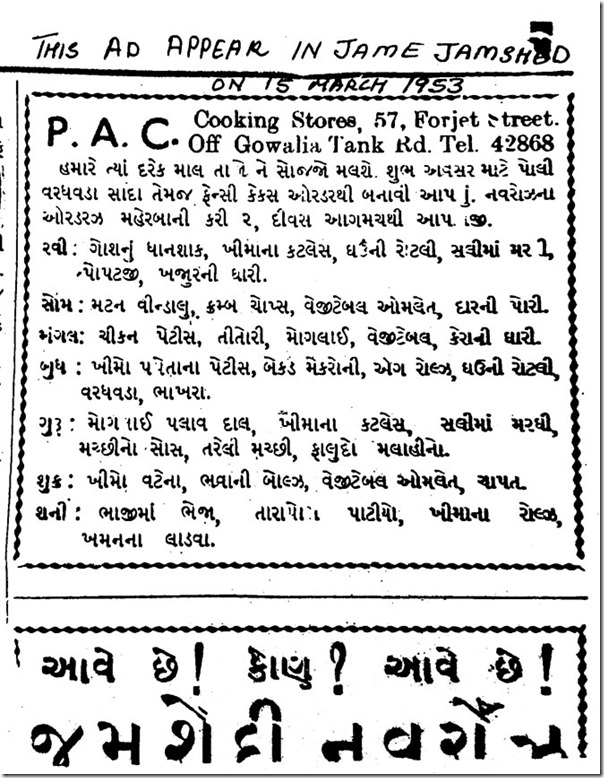

A 1953 ad in the Jam-e-Jamshed Gujarati newspaper lists the daily change of menu specialties at PAC Confectioners for the festive week before Spring Equinox (Jamshedi Navroze) celebrated by Zoroastrians on March 21

Along the rubble track, past a rest-house for Jain monks, Nilesh Amonkar enquires: “Kitne aadmi hain…” Adding “Santro ke neeche?” to the Gabbar-ish question, he believes Forjett Street stays basically unchanged. This space was where his father was a mechanic with Rusy Lang & Co. from 1947. Taking on the service station in 1965, Sitaram Amonkar gave his name to Sitaram Auto Works and training to Nilesh young as 11. Stopping for lassi at Vora’s dairy, actor Vinod Khanna used to drive his car to their garage for repairs.

The famous Amonkar in the area was, of course, Kishori. Her Jaipur gharana singer mother Mogubai Kurdikar, from Motiwala Mansion, asked Anwar Hussain Khan in next door Ruby Mansion to more diversely expose her daughter to the Agra gharana. Mogubai, herself a pupil of that clan of maestros, was taught by Vilayat Hussain Khan and Basheer Ahmad Khan. I’m directed to this Hindustani vocalist haven by marine engineer Sudhir Kerkar and his teacher wife Shubhada, also in Motiwala Mansion. “Our Ruby Mansion remains a music mandir,” says Anwar Hussain Khan’s son Raja Miyan. His uncles, the great Vilayat Hussain Khan, Khadim Hussain Khan (Raja Miyan’s guru), Azmat Hussain Khan, Anwar Hussain Khan and Latafat Hussain Khan tutored legions of talents. It was joked that a stone thrown from Ruby Mansion’s terrace would hit the building of one of their students. Yakub Hussain Khan, Aslam Khan, Raja Miyan Khan and Rafat Khan continue to teach inspiringly.

At the gate of Saibaba Mandir, cramped in Haji Mohamed Kasam Building in the same compound, Billoo phoolwala plies his father’s trade of 50 years. Devotees garland the Shirdi saint’s four-foot statue on a teak altar within. Nudging it is an image of Yogiraj Dattadas Madiye Maharaj who helped raise the temple in 1942. The philosopher was the maternal uncle of Gurunath Mayekar, whose family tends the temple till today. Like the florist outside a mandir, no prasad stall lags far. Arriving from Keraket village in Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh, Arvind Gupta’s family hawked offerings from Saibaba Chana Shop – currently Bharat Bhelpuri and Farsaan. Similarly symbiotic, Satale the vegetable vendor doubled business selling vada pao and bhajias, nibbled hot with country spirits from Chhaya Bar. That joint witnessed one of the city’s worst liquor tragedies on New Year’s Eve in December 1991 when hundreds died of methyl alcohol poisoning.

A resident of Jhamb House (old Darab House), movie mogul K Asif patronised 100-year-old Alfred Laundry, which Vijay Rajput’s grandfather bought from a Parsi gent. Naseem Dhariwala invites me to her second floor flat that belonged to Asif’s wife Nigar Sultana. It came with her opulent carved furniture and chandeliers yet filling the hall. Midway down the road, around Spencer Company, once the Johnson & Johnson offices, tower power threatens a century of dhobi ghat paths worn needle-narrow. Gokuldas Chawl opposite is already razed to redevelop. Tabela turf originally, the labyrinthine ghat heaves with a dizzying 165 shanty kholis. Dodging drains and bumping bundle-loaded bicycles, I hear 80-year-old Dayaram Pardesi declare he will wash clothes till his dying day, while Rampher Dhobi recalls his grandfather Mahavir migrated from Rae Bareli to life among the soap suds.

The street bends north at Sethna Agiary and Jaiphal Terrace, the latter left neglected after 108 years. From Mehra Mansion’s front windows Jaffer and Suraiya Diwan point to comedian Satish Shah’s home opposite in 1956-erected Anand Nagar till he moved to the suburbs. Their building shares a rear wall with the fire temple. The Diwans introduce me to Pervez Dordi, pilot turned panthak (presiding priest) in 1967. Following his father Barjorji Dinshaji Ratanji Dordi, he is fourth generation keeper of the holy flame here.

Trying to locate less genteel Forjett Street’s sailor haunts, boarding lodges and brothels, I stumble upon a sepia ad in a 1936 edition of the American pulp magazine Weird Tales: Isle of the Dead. Deliciously titled “Let me tell you”, it announces: “Pundit Tabore, Upper Forjett Street, Bombay VII, British India… Private astrological adviser to royalty and the elite… All work strictly scientific, individual and guaranteed satisfactory.” Mightn’t Forjett have doffed his (disguise) hat to that?

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at mehermarfatia@gmail.com