Remembering an episode form legendary jurist Nani Palkhivala’s life on his 18th death anniversary

When Nani Palkhivala entered the Supreme Court to argue Kesavananda Bharti, India’s future rested on his shoulders. The case was to be heard by a mammoth bench of 13 judges, and their decision would decide the fate of the largest democracy in the world. Palkhivala knew that this was to be an uphill battle, especially because he was to go up against a celebrated jurist and his long-time friend from Bombay, H. M. Seervai.

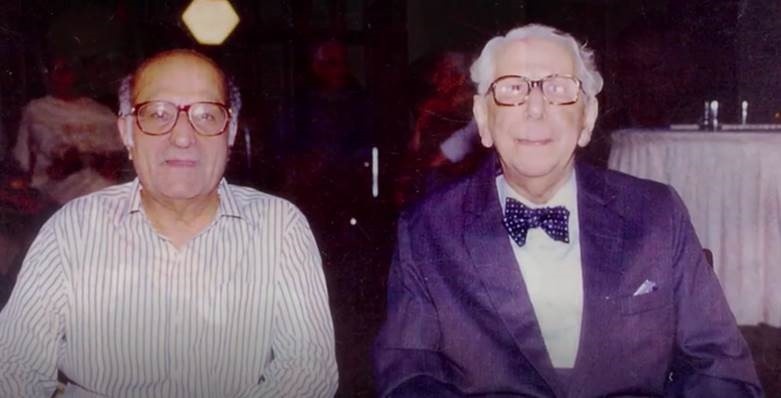

Nani Palkhivala and H M Seervai (Image Source : ‘Nani, The Crusader’, Documentary)

Remembering an episode form legendary jurist Nani Palkhivala’s life on his 18th death anniversary

When Nani Palkhivala entered the Supreme Court to argue Kesavananda Bharti, India’s future rested on his shoulders. The case was to be heard by a mammoth bench of 13 judges, and their decision would decide the fate of the largest democracy in the world. Palkhivala knew that this was to be an uphill battle, especially because he was to go up against a celebrated jurist and his long-time friend from Bombay, H. M. Seervai.

Seervai and Palkhivala had a lot in common. Both of them grew up in middle-class Parsi families in Bombay and studied law at the Government Law College. Upon graduating, both joined the chambers of the legendary Sir Jamshedji Kanga and cut their teeth at the Bombay High Court. Not only were they friends and colleagues in the same chamber, but at one point, Seervai was also Palkhivala’s lawyer. Under Jamshedji Kanga’s supervision and advice, Palkhivala had authored a commentary on Income Tax titled ‘The Law and Practice of Income Tax.’ A. C. Sampath Iyengar, who practiced in Madras, sued Kanga and Palkhivala claiming that they had plagiarized his renowned commentary on the Income Tax Act. Seervai argued the matter on behalf of Palkhivala and Kanga. The court ruled that there was no copying and observed that the suit was ill-advised.

While Palkhivala was consulted in the very early phases of the case, he wasn’t the first preference for lead counsel in Kesavananda. Kesavananda Bharti had originally approached M. K. Nambiar, who refused the brief citing ill health. The original arguments were then to be led by M. C. Chagla, former Chief Justice of Bombay High Court. Chagla, who was then an old man, felt that the burden would be too great, and therefore suggested that former Attorney General C. K. Dapthary take lead. Dapthary, who too was in his older years, turned down the request. It was Chagla and Dapthary who then suggested that Palkhivala be approached for the task.

On the other hand, the Government had chosen Seervai as the lead counsel over the Attorney General for India to defend Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution. This led to a dispute between Seervai and the then Attorney General, Niren De. Seervai had accepted the job on the condition that he would be allowed to make submissions first. De felt that the Attorney General, who had the right to pre-audience, was being rendered subordinate to Seervai, and therefore refused. This dispute eventually came to an end when Seervai chose to appear on behalf of the State of Kerela, which was the first respondent and suggested that De follow him on behalf of the Union of India, who was the second respondent. A reluctant De eventually agreed to give up on his right to pre-audience.

The hearings began on 31st October 1972 and lasted until mid-March – some seventy working days at four and one-half hours daily. Palkhivala argued for 33 days. He argued that the creature of the Constitution could not amend it to increase its own constituent power. Judges questioned Palkhivala mercilessly, and he answered every one of them. When Palkhivala was done arguing, Dapaphtary and Chagla argued on finer points. Seervai led the rebuttal and opened for the State of Kerela. He hammered home his arguments and maintained that it would be gross irreverence to assume that Parliament would abuse its unlimited legislative power. Soon after Seervai finished, De took the stage. He reiterated the position the government had taken in Golak Nath: in written constitutions, there could be no inherent limitations on the amending power. Palkhivala then stood up to reply to Niren De’s arguments. He submitted that that citizens need protection against their own representatives and that only those Directive Principles compatible with the Fundamental Rights had been included in the Constitution. From this point onwards, things were about to get serious.

Just when he was about to end, Palkhivala decided to lighten up the mood and spice up his arguments. He told the court that he wished to read views supporting his arguments expressed some years ago by an eminent jurist. “Was it not time ‘we rekindled’ the inspiration behind the fundamental rights, including ‘just compensation’ and the freedom to carry on a business and acquire property” – the anonymous jurist had asked. Palkhivala continued reading, “There were ‘grave consequences’ to treating the constitution ‘as ordinary law to be changed at the will of the party in power’. If governments always could be trusted, there would have been no need for Fundamental Rights”. Palkhivala’s anonymous jurist was well received by the court. When asked who the jurist was, Palkhivala revealed that his eminent authority was none other than Seervai.

Seervai was furious – he considered this a blow below the belt. Palkhivala has cornered him with his own arguments in an open courtroom. Seervai had no choice. If he agreed, he’d be letting down his client. If he disagreed, he’d be abandoning his own work. This left Seervai feeling embarrassed and betrayed. The two lawyers who once worked in the same chamber under Sir Jamshedji Kanga did not speak for many years. Palkhivala had won the case but lost a friend in the process.

The misuse of the amending power during the Emergency in 1975 by the ruling party made Seervai change his view of the law expounded by him in Court. He later stated that there had to be limitations on the Parliament’s power to control the Constitution. Seervai had the intellectual courage to change his view. Both Seervai and Palkhivala were men of immense standing. It took some time, but the two Bombay legends eventually settled their differences and repaired their relationship.

[Hamza Lakdawala is an aspiring litigator, researcher, and writer from Mumbai. He studied Journalism at Mumbai University and is currently pursuing his LL.B. at Kishinchand Chellaram Law College, Mumbai. You can follow him on Twitter @hamzamlakdawala]

References:

1. Soli J Sorabjee & Arvind P Datar. Nani Palkhivala The Courtroom Genius. Lexis Nexis; 2012

2. Austin G. Working a Democratic Constitution: A History of the Indian Experience. Oxford University Press; 2003.