The South Asian American Digital Archive announces

This collection of oral histories represents the living and lived histories of Zoroastrians from South Asia who’ve migrated to the United States in the past fifty or so years. In 1965, after many migration quotas were abolished, the number of South Asian-born migrants increased, which contributed to Zoroastrian mass migrations to North America. They left behind their “home” countries and settled down throughout the Global North. The Zoroastrians in this collection now reside in various states across the United States, majority of whom are in New York, Virginia, Texas, and California.

They have deepened their community ties by participating and volunteering their time during community gatherings, such as Nowruz celebrations or teaching children about Zoroastrianism at their local community centers. They are writers, artists, journalists, professors, priestesses, business owners, and they all have a story to tell. The stories documented in this collection and the archival objects that hold memories of home and their migration journeys portray a transformational process in which interviewees remember and dialogue about their subjective historical knowledge.

In particular, these stories reflect upon what it means to cultivate a new home away from the close-knit Zoroastrian communities in South Asia and what exactly the Zoroastrian identity means in the diaspora. They talk about what it means to be a Zoroastrian in the United States and what the act of remembering and retelling these stories brings to the fore about how we carry our homes, our loved ones, and our histories with us in our daily activities and lives. In these audio recordings, our conversations tackle current topics in the Zoroastrian communities regarding our ancestral history, Iranian and Parsi Zoroastrians, interfaith marriages, representation of the LGBTQ members in the community, and other significant conversations that Zoroastrians in their local communities are paying attention to and voicing concerns about.

Interviews: Sharmeen Mehri | Artwork: Leea & Zara Contractor

“What is homeland? To hold on to your memory — that is homeland.”

– Mahmoud Darwish, The Homeland (tr. Ibrahim Muhawi)

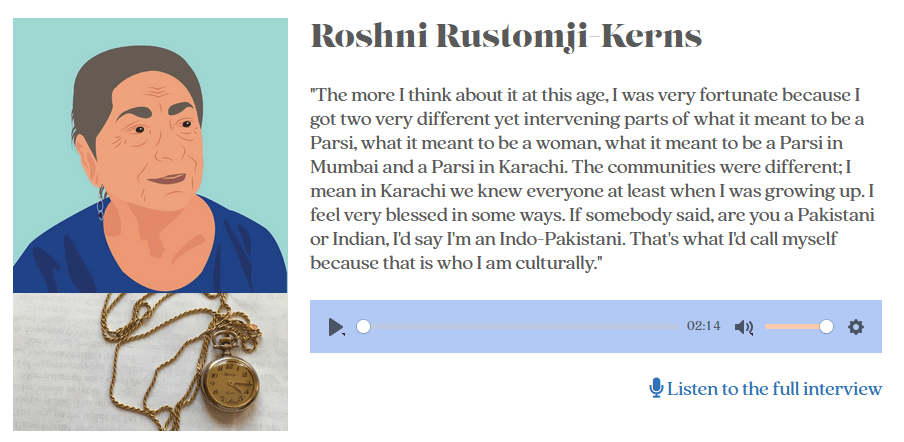

Roshni Rustomji-Kerns

“The more I think about it at this age, I was very fortunate because I got two very different yet intervening parts of what it meant to be a Parsi, what it meant to be a woman, what it meant to be a Parsi in Mumbai and a Parsi in Karachi. The communities were different; I mean in Karachi we knew everyone at least when I was growing up. I feel very blessed in some ways. If somebody said, are you a Pakistani or Indian, I’d say I’m an Indo-Pakistani. That’s what I’d call myself because that is who I am culturally.”

Fram Haveliwala

“Having an entire community, we understand each other right. We understand our upbringing, we understand the similar housholds we grew up in, and we really understand our background and who we are today as people because not a lot of people know about Zoroastrianism so it’s always great having a common bond with people who you’ve grown up with and have that upbringing in the same way.”

Meher

“I feel like I’m more Zoroastrian in my philosophy now than I was then. Yes, while I had all the trappings of the cultural stuff that makes me Parsi, in America, I’m more Zoroastrian in beliefs and in ways that matter that are not cultural. It’s not about wearing the Sudreh Kusti or it’s not about going to the fire temple or praying everyday several times a day or covering your head while praying. Those are all just sort of external and physical things. I think internally, the way I live my life is more Zoroastrian here than it was even in India.”

Teshtar, Noshir, & Kayhan Irani

Teshtar: “Oh what a lovely home I had, what a lovely home. I wish it was there. In Bombay, it was in Shapur Baug, which is a Parsi colony. We practically grew up with our neighbors and you knew everybody’s neighbors, relations, and relatives. And everyone played together, ate together.”

Tahmoures Hormozdyaran

“My name is very different. The challenge is only Iranians can relate to it. If I tell a Pakistani that I’m from Pakistan and this is my name, they literally go, what kind of a name is this? And same with the case with Indians, if you tell them I’m a Parsi but my name is so and so, I have to explain to them, I was born in Iran and this is my original name. My parents were Iranian. But obviously I can relate to all of them, even if I’m sitting with Iranians, I can speak Farsi. I can with Indians, also with Pakistanis so I mean the language is not the issue, but it’s really a difficult issue because of my name.”

Zenobia Panthaki

“Now we’ve been her for a while, what we’ve noticed is that there has been a realization that we are not doing this for ourselves, we are doing this for the next generation. So, the children don’t see themselves as Indian, Pakistani, Iranian. They see themselves as American Zoroastrians. They speak English, they want American food, and that is why we have to curb this desire to look inward to ourselves and we have to be more all-encompassing and inclusive. It’s for the sake of the next generation.”

Zarrah Birdie

“It’s this feeling of empowerment that as an immigrant I always felt like I’m in the US and now I just have to be here. I can’t go back home and I had to like kind of disassociate my sense of home. And now it’s not that way anymore, and I feel really grateful for that. There’s a lot of me that will always live there and a lot of who I am is determined, was determined or was influenced, it was inspired by my life there.”

Anahita Sidhwa

“Living through that experience, not knowing whether I would have to go back to Pakistan and live apart from my husband, when we had just been married, it did weigh on you a lot. You know I was twenty-five years old when I left Karachi, twenty-seven when I got married, twenty-nine when I went back, but those four years in some respects were difficult in how much I missed my family.”

Havovi Cooper

“Living inside a Parsi colony is weirdly calm and you leave all the chaos behind. One memory that I have is pretty distinct. There was an Agyari or a Parsi Fire Temple that was in the same complex and every time the gehs changed, the gehs being the time of the day, the bells would ring. And the bells signified where the gehs were. So if it was early morning, there were a certain number of bells and if it was afternoon, there are a certain number of bells and I have this soundtrack in my mind of hearing this when I was growing up.”

Ms. Be The Change

“SO ‘Zara-who? Zoro-who?’ was the typical response… We can make the change in society that we want to see by gentle teaching, by gentle sharing, by even encouraging people to participate in our food. Start first with our food, then understand our practices, then understand my Haft-seen table that I put out at Navroze.”

Sharmeen Mehri (she/her) is a Pakistani international Ph.D. student in the English department at the University at Buffalo. Her research focuses on postcolonial theory and literature with an interdisciplinary focus on archival and visual studies. She completed her Master’s degree at Hunter College, CUNY where she was a dedicated writing tutor and teacher of writing and rhetoric. Her research project will seek to examine and preserve the migration experiences of Zoroastrian South Asians to the United States. With a specific focus on the narrative of assimilation or dissimilation, she will carry out and collect oral interviews to highlight an often-overlooked minority group in the South Asian diaspora. By recording a diverse range of voices, this archive will document how Zoroastrians preserve or adapt their cultural expressions within the context of the broader American immigrant experience.

The Archival Creators Fellowship Program is made possible with support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Read Sharmeen’s writings about her fellowship project in TIDES:

• A Quotient of Sweetness

Learn more about the artists Zara Contractor and Leea Contractor.

Contact Sharmeen Mehri for queries about her project.