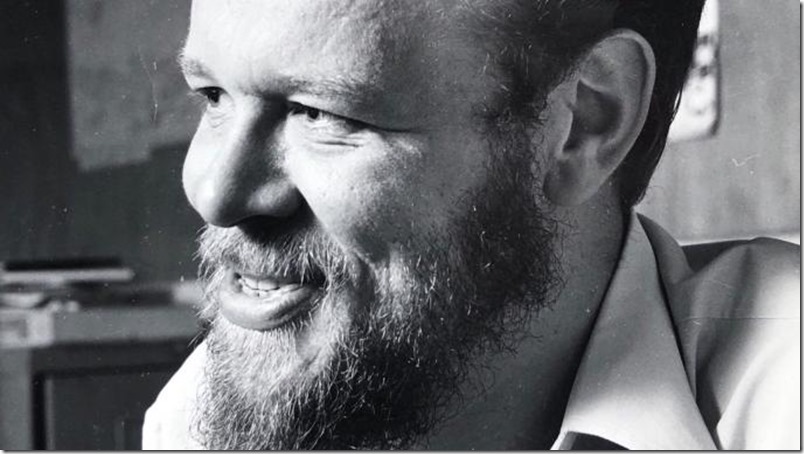

Determined expert on Zoroastrianism who founded degree courses on world religion and zipped across the world on crutches

As a child sick with tuberculosis of the bone, John Hinnells spent the best part of seven years isolated in hospital. When he was as young as six years old he was placed on wards full of adults. Only on Saturdays could his parents visit and John would weep as they left. He made sporadic appearances at school, missing months of teaching. “You’ll never work when you grow up” was a frequent taunt. Yet Hinnells, the son of a Derbyshire miner, possessed grit and resilience. Briefly suspended from school for tripping up his tormentors with his crutches, he left with the equivalent of 3 O’ levels. This proved no obstacle to a glittering future in academe.

Published in The Times London

Once a novice monk, he was drawn east to study the roots of Christianity. Later he became an authority on Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest faiths, which originated in Persia (modern-day Iran). Sometimes obliged by his ailment to lecture from a wheelchair, Hinnells founded four degree courses in world religion at Manchester, Newcastle, the Open University and Soas (the School of Oriental and African Studies). Remarkably he also managed, while using crutches, to zip across the world from Zanzibar to Canada to survey the Zoroastrian diaspora. Staying with modern followers of the Persian prophet Zoroaster, he asked searching questions of their religious beliefs while savouring slow-cooked aromatic curries. He relished Bombay, once missing a flight because an elephant was squatting on the road to the airport. And he found Indians especially kind when they saw his physical difficulties. His frame was contorted, with one leg shorter than the other. Stoically he endured his knees being replaced and many operations on his feet. With a stiff, straight leg secured by pins he was unable to sit down, and could only perch on chair edges. By his thirties doctors suggested to Hinnells that he consider amputation. He always refused, and at a party met an orthopaedic surgeon who suggested that Hinnells should try a hip replacement, an operation then in its infancy, at the Wrightington Hospital, Wigan. “I’d like to do something I haven’t been able to before,” announced Hinnells, after successful surgery. Fearlessly he embraced white-water canoeing with his wife and sons. He had never let physical difficulties get in the way of adventure. Once with a friend he scaled Thorpe Cloud at Dovedale in Derbyshire, encased from chest to toe in plaster. Reaching the summit, he decided that navigating down on crutches was too tricky. So he gleefully slid down on his bottom, burning a hole as he did so in his plaster.

John Russell Hinnells was born in August 1941 in Derby, the only child of William, who after mining worked on the railways, and Lillian (née Jackson), a dinner lady and school cook. At the age of 13, Hinnells won a place at Spondon Park Grammar School in Derby. He taught art after taking a course at Derby and District College of Art. Sensing a call to priesthood, he began training in Cumbria then entered Mirfield Monastery near Leeds. His plans for a life with the Anglican Community of the Resurrection changed the day he met Marianne Bushell, a visitor whose cousin was at the monastery. Smitten, within 24 hours of first meeting they vowed to marry. Marianne (always known as Anne) and Hinnells married in 1965 after he had obtained a degree in theology from King’s College London. She taught literacy to children, and was a calm counterpoint to her husband’s taste for debate. Around the dining table of a home adorned with brass lamps and vibrant Bombay rugs, Hinnells sparked discussion with his sons, Mark and Duncan, on the increasing importance of world faiths because of global migration. How, he asked in a light Derbyshire burr, might religion influence social policy? Hinnells had obtained a lectureship at Newcastle when he was 26 and from 1970 worked at the University of Manchester, where he was made the professor of comparative religion. In 1993 he received the chair of comparative religion at Soas in London and became the founding head of its department for the study of religion. Geographers and sociologists alike were intrigued by Hinnells’s 30-year investigation into the world’s Zoroastrians that was published in 2005. More than 1,800 answered a questionnaire he devised that pinpointed religion as a key marker in the identity of migrants from southeast Asia.

As an adviser on religions to Penguin, Hinnells also edited succinct guide to faiths, including the Penguin Dictionary of World Religion (1984). Other scholars offered the project felt swamped by its scope. However, by 8am daily Hinnells was in his study rattling out letters on a manual typewriter requesting contributions from the world’s most prestigious religious scholars. He asked Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, Zoroastrians and Jews to write of their beliefs, at a time when accounts of world faiths were largely penned by western Christians.

At home he relished entertaining ministers of all faiths, including the Parsee High Priest, who was one of his friends and was often spotted in Hinnells’s garden lobbing a cricket ball to his sons. After Marianne’s early death from cancer in 1996 a devastated Hinnells left Soas and took up a visiting fellowship at Clare Hall, Cambridge. Later he invited Alison Houghton, the widowed former librarian of Robinson College, to share his bungalow. She had Alzheimer’s disease and they made a solid team — he was the memory, she was the manpower. Hinnells would remind her to switch off the gas before they left for trips to the Buxton opera festival. She carried the bag he could not pick up. Later Hinnells moved near his older son, Mark, who works for the engineering firm Ricardo. Although he was frequently unwell, his death was unexpected. After falling ill while sharing a meal with Mark, he was diagnosed with septicaemia in hospital. Surgery was planned, but Hinnells asked if he might sample his favourite beverage. “No,” said the doctor. “It’s nil by mouth if we operate.” The next morning he said that Hinnells was not well enough for surgery. Agreeing and aware that this meant death was imminent, Hinnells merely replied: “Can I have that Diet Coke then?” The many letters sent to his sons since his death speak of how often he helped others, whether that was with securing a university place, a book deal or a lectureship. “Dad saw what people were capable off,” recalled his son Duncan, who is a solicitor. Perhaps his own struggles inspired him.

Hinnells’s mother once bumped into her son’s former headmaster. He mentioned hearing that Hinnells had become a university lecturer. Assured that this was untrue, the headteacher replied, “I thought not,” only for Lillian to gently smile. “John,” she replied, “is now a professor.”

John Hinnells, professor of world religion, was born on August 27, 1941, and died on May 3, 2018, aged 76.