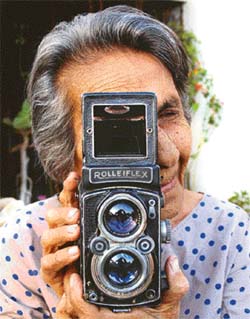

NO, no, no. No blinding flash, not again,” shouted Mahatma Gandhi, the apostle of peace, as the Parsi photographer, a woman in her early thirties, clicked her camera using a big bulb for flash. “Gandhiji was a trifle annoyed as he came out of a prayer meeting on that winter evening,” recalls Homai Vyarawalla, 93, India’s first woman photojournalist who worked at Delhi from the 1940s to 1970, chronicling in pictures the nation’s tumultuous march to Independence and after.

Homai’s remarks came in response to a question if she had talked to the Mahatma during her long stint in the capital. To my surprise and in a casual, matter of fact way, she said: “No, never. Yes, he scolded me once.” Then she recalled the incident in a chat that brought out her character as a thorough professional who kept a distance from her subjects and refused to be over-awed into hero worshipping. This perhaps distinguishes her from the average photojournalist, who, given fame and experience, would have been too willing to drop names and claim proximity with the great and mighty.

Homai, living alone and in total anonymity in Baroda since the past three decades, was persuaded by the Parzor Foundation, dedicated to the preservation of Parsi-Zoroastrian culture and heritage, to share her memories and photographs with the world in the form of a book. Parzor chose Sabeena Gadhioke of Jamia Millia University as the researcher and writer.

Homai’s work, as narrated in the book, speaks to the reader through amazingly clear black and white pictures.

Though employed by the British Information Services, Homai was allowed to pursue a parallel career as a photographer. She was an active witness to an era, having a ringside view of events that shaped India’s destiny. Her comments on the happenings enhance the historical value of her photography. World War II was the backdrop for some of her earliest pictures that documented the efforts of women to provide utility services. These, along with others, were published as photo-stories in the Illustrated Weekly of India, Time, Life, The Black Star, Paul Popper and other international publications.

Homai with Sabeena Gadihoke, her biographer, at the release of the book in Delhi

Homai with Sabeena Gadihoke, her biographer, at the release of the book in Delhi

From Lord Mountbatten to Marshall Tito, from Queen Elizabeth to Jacqueline Kennedy, from Khruschev to Kosygin, from Eisenhower to Nixon, Atlee, Nasser, Chou En Lai and a host of others, who charted the course of history during the 20th century, were all caught by her camera. The exhibition displays hundreds of Homai’s pictures that are not only historical, but also funny and irreverent in good measure. For example, savour the one that shows Nehru on the field outside the Palam runway beside a signboard with the legend “Photography strictly prohibited.” Homai took the snap as Nehru was awaiting the arrival of the Moscow flight carrying his sister Vijyalakshmi Pandit, India’s ambassador to the Soviet Union.

Not many know that Nehru was a chain-smoker. An interesting glimpse of the revelation is in Homai’s photo that shows Nehru with a burning cigarette on his lips, lighting the one on the lips of Ms Simon, wife of the then British High Commissioner to India. The photograph was taken inside the BOAC Boeing on its inaugural flight to London from New Delhi. “The plane had crashed on its second flight,”remembers Homai.

There is one showing Indira with husband Feroze Gandhi in a Gandhi cap. An inadvertently irreverent picture is that of Nehru seemingly pulling at the beard of the Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh. In fact, Nehru is introducing him to someone with his left hand pointing to the bearded dignitary and that appears as if he is pulling at the beard. For long, Homai did not display the photo lest it should show Nehru as being inelegant.

“Today, an average photograph is cluttered with too many things and lacks focus.”

Keeping a low profile, she shunned the glare of publicity. “I was very stern — no hanky-panky and no unnecessary smiling which could be misconstrued. I would stand in a corner watchfully, taking pictures as the opportunities came. The other photographers would leave soon after they had taken their routine shots but I would always wait for an out of the ordinary picture,” she told an interviewer recently.

Her biographer Sabeena Gadihoke says: “She an incredible person, a great role model.” Despite her credentials of fame and celebrity status, Homai has never gone abroad, a fact hard to believe in one belonging to a glamorous field. K. Natarajan, 84, a veteran press photographer, is perhaps the only living contemporary of Homai. “She was a great professional and dedicated to her work. She was also friendly and warm-hearted. On my request, she came and took my wedding photos in Delhi in January 1952,” Natarajan, who is still active in Delhi, remembers.

Excerpts from an exclusive interview with Homai:

Is it true you missed Mahatma’s assassination?

Yes, most regrettably (smiles and throws a vacant glance at the ceiling). I remember I had planned to go to the prayer meeting on that fateful day. As I prepared to go to Birla House that evening, my husband hurriedly called me back, suggesting we go for the next day’s prayer meeting. When I received the terrible news I was stunned and struck by conflicting emotions. As an individual I was deeply saddened by the assassination. At the same time my professional self agonized over not being on the spot, though being so near. My husband wouldn’t forgive himself for calling me back.

Whose is the most photogenic face that you came across?

Undoubtedly, that of Pandit Nehru.

Did you ever talk to him?

No. As I said earlier, I always kept a distance from my subjects. That, I think, gave me the professional freedom and also helped me have an objective view of people and events.

What is your most memorable or amusing experiences?

There are quite a few. The US Chief Justice Warren and his wife were on a visit. I followed them to Agra on their visit to the Taj. It was May and burning hot. I climbed on to a wall to get a good view of the couple before the marble monument. I suddenly lost balance and fell into the water of the pool below me .I held my camera above water and saved the snaps. Mrs. Warren came to me and quipped: “How I wish I could do that. It’s so very hot!”

On another occasion I had hurt my lips and it was bandaged while I attended some ceremony. Dr. Radhakrishnan, who was present on the occasion scratched his lip at the point where I had the bandage. “Did your husband bite you?” asked the philosopher-president with a twinkle in his eyes as he passed me by after the ceremony.

Did you not take any photographs of film personalities?

Yes, I did. I have lost both the prints and negatives of most of them.

What about sports?

Not much. Yes, a bit of athletics and other games. I covered some events in the first Asian Games in 1951. Polo, for example and a bit of cricket which I did not like much in any case.

How is photography different from your days?

The tremendous advance in technology is one difference. In the past, the equipment was all you had, there was no metering system, no automatic flashes. One learnt and mastered by trial and error alone. Now the camera does it all. I would be at a loss to know what to do with a modern camera. But composition still remains the most crucial aspect of photography. Today, an average photograph is cluttered with too many things and lacks focus. One has to read the caption to comprehend the image.

Why did you leave active profession?

My last picture was in 1970–that of Indira Gandhi. When my husband died in 1969, I decided to leave Delhi. It was as well, because a disturbing change was taking place in the profession. In my times, photographers were educated and carried themselves with dignity. Though a solitary woman, I never had any problems as my colleagues treated me with the grace and dignity of gentlemen. Many in the following generation migrated from the darkroom, drawn by the glamour of the profession. The environment is not the same, I am afraid.

You share a birthday with Sonia Gandhi (December 9)? Are you in touch with her?

Homai: (Laughs) Do I ? I don’t know. No, as I said, I never kept contact with my subjects. Yes, I have taken the photographs of Sonia’s wedding with Rajiv. — R.C.R.

Interview here