In a manner of speaking, Air India, India’s foundering national airline, turns eighty on Monday – an octogenarian that started life with a spry hop from Karachi to Bombay. It should be a proud moment, except that it serves only to remind us of the irony that one of India’s most dilapidated public-sector companies was launched by – and then wrested away from – one of India’s most successful private corporations.

By By SAMANTH SUBRAMANIAN | India Ink NYTimes

|

|

Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, third from left, with Nevill Vintcent on his left, at the Juhu airstrip in Bombay (now Mumbai) on Oct. 15, 1932 after the inaugural flight of Tata Aviation Services. |

For Jehangir Tata, whose father’s cousin had founded the Tata group in 1868, an obsession with flying began early. Much of young Jeh’s boyhood was spent in the French town of Hardelot, where his family’s beach house stood near another owned by Louis Blériot, the first man to cross the English Channel in an airplane. After Charles Lindbergh flew solo across the Atlantic in 1927, Mr. Tata sketched an ink drawing of Mr. Lindbergh’s plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, in his scrapbook. Just 12 days after a Flying Club opened in Bombay in early 1929, his biographer, R.M. Lala, recounts in “Beyond the Last Blue Mountain,” Mr. Tata had logged enough hours to fly solo; a further week later, he had his blue-and-gold pilot’s license, issued by the Aero Club of India & Burma and serial-numbered 1. “No document has ever given me a greater thrill,” Mr. Tata would tell Mr. Lala many decades later. The photograph in the license shows a lissome Jehangir Tata, not yet 25, his hair slicked back with pomade, a toothbrush moustache perched perfectly below his nose, and his clear-eyed confidence spilling out of the frame.

|

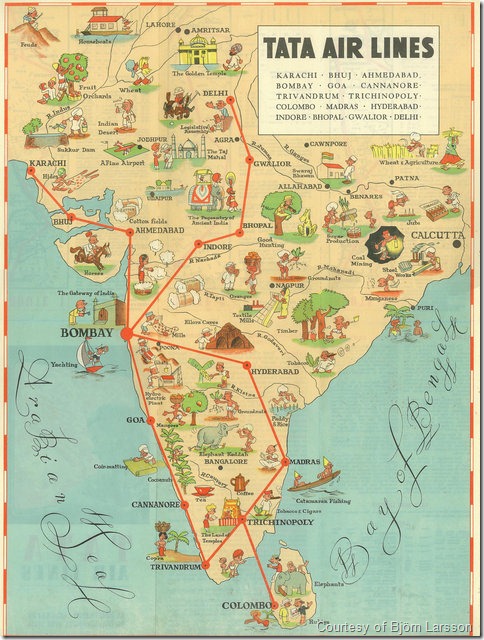

| Image Copyrights Björn Larsson |

Until November 1929, Mr. Tata contented himself with harum-scarum joyrides in India and Europe; in that month, however, he spotted the Aga Khan’s announcement of a 500-pound prize for the first Indian to fly solo between England and India. This was serious flying, and Mr. Tata could not help but be interested. (It is almost too delicious that one of Mr. Tata’s rivals for the Aga Khan’s prize was a pilot named Manmohan Singh, who, having taken off from Croydon, first lost his bearings over the English Channel and then, on a second attempt, found himself flummoxed by fog over Europe. A magazine named Aeroplane remarked: “Mr. Manmohan Singh called his aeroplane ‘Miss India’ and he is likely to!”) From Karachi, Mr. Tata flew via Basra, Cairo and Naples, but by the time he reached Paris, another pilot, Aspy Engineer, had flown the same route in reverse and already landed in Karachi.

As far as aviation was concerned, therefore, Mr. Tata was already dry tinder. The spark came from Nevill Vintcent, a former prizefighter from South Africa and a Royal Air Force pilot who was barnstorming his way across India in the late 1920s. When he expressed, into the right ears, his desire to start a commercial air mail service, Mr. Vintcent was introduced to Mr. Tata. During a series of conversations with Mr. Lala, collected in a book called “The Joy of Achievement,” Mr. Tata said about Mr. Vintcent:

He was remarkable. A very fine man … He knew, the man that he was, that the Imperial Airways Airline was coming to India, to Karachi, as a first step towards Australia … but they would also go across to Delhi and Calcutta. The whole of south India would be blank and unserviced, and that’s how he worked out a proposal to have a flight from Karachi to Ahmedabad to Bombay to Madras.

In Air & Space magazine, the journalist David Shaftel described how, writing to Mr. Tata in 1931, Mr. Vintcent presaged the debate over the liberalization of Indian aviation by several decades: “If the route is state operated I maintain that it will effectively put a stop to any further efforts by private firms to develop other routes, as they will argue that after the spade work has been done, the state reaps the benefit,” Mr. Vintcent wrote. “I also maintain that private enterprise will develop flying far more quickly than the state can hope to do, and will consequently provide more openings for Indians in this profession.”

Poor mid-September weather forced Mr. Tata to push his inaugural flight to Oct. 15, when he took off, with more than 100 pounds of mail, in a single-engine De Havilland Puss Moth, from the Drigh Road aerodrome in Karachi. (Mr. Vintcent would fly the second leg, from Bombay via Bellary to Madras.) By train, the Karachi-Bombay route needed 45 hours to complete; Mr. Tata touched down on the mud flats of Juhu in less than eight hours, having stopped off in Ahmedabad to refuel his plane from four-gallon Burmah-Shell petrol cans transported to the runway on a bullock cart. The postmaster of Bombay himself ceremonially collected the mail from Mr. Tata in Juhu; indeed, such an acute sense of occasion marked the entire enterprise

that the envelopes – like the one addressed to “A. Achutten, Esqr., General Merchant, Bramagiri, Udipi” – were franked “Karachi-Madras, First Airmail.”

A photograph taken after the landing in Bombay shows Mr. Tata standing with his colleagues, left arm akimbo, his white trousers still so uncreased and his hair so immaculately in place that he looks for all the world like a county cricketer just about to have a leisurely bat before lunch. In reality, Mr. Lala reveals in “Beyond the Last Blue Mountain,” the flight had been hot and bumpy, and Mr. Tata battled headwinds throughout. Part of the way through, an unfortunate bird flew into Mr. Tata’s cabin, forcing him to kill it before it endangered his flying. But in a conversation with Mr. Lala years later, Mr. Tata remembered that first flight as “delightful … We were a small team in those days. We shared successes and failures, the joys and heartaches, as together we built up the enterprise which later was to blossom into Air-India and Air-India International.”

Having convinced the government, in 1932, that he should run an air mail service for it, 28-year-old J. R. D. Tata did not need much longer to demonstrate that he was doing a stand-up job. Tata Air Mail’s scrupulous adherence to schedules was legendary. Only a year into its operations, the Directorate of Civil Aviation wrote in a report:

“As an example of how air mail service should be run, we commend the efficiency of Tata Services who on October 10, 1933, arriving at Karachi as usual to time, completed a year’s working with 100 per cent punctuality… Our esteemed Trans-Continental Airways, alias Imperial Airways [the British carrier], might send their staff on deputation to Tatas to see how it is done.”

Tata Air Mail made a profit of 60,000 rupees its first year. By 1937, that profit had risen to 600,000 rupees. Auxiliary routes were developed, but its main one continued to retrace the 1932 trial run by Mr. Tata and Nevill Vintcent, skipping from Karachi through Ahmedabad and Bombay to Madras. A handsomely illustrated 1935 timetable (mentioning, as an aside, that “Tata Air Mail ‘Planes are lubricated with Mobiloil”) reveals that a letter from Karachi to Madras would leave on Monday between 6 and 6:30 a.m., pass through Ahmedabad four hours later and Bombay around lunchtime, spend the night in Hyderabad, and arrive at the Madras airport at 9:55 a.m. on Tuesday.

In 1938, just after Mr. Tata changed the name of his company to Tata Airlines, he began to run regularly into a fickle and obstinate government, a process of attrition that wearied and exasperated him for the next 15 years. During World War II, the government commandeered all his aircraft. When he offered to manufacture the De Havilland Mosquito in India, he was first encouraged and then instructed to make gliders instead. Not long thereafter, the government cancelled the contract because, ironically, it didn’t have airplanes to tow the gliders – the very airplanes that Mr. Tata had offered to make in the first place.

Mr. Vintcent, Mr. Tata’s chief collaborator, died in 1942, when a military airplane he was traveling in was shot down off the coast of France. Nevertheless, Mr. Tata continued to prepare, as he later told his biographer R. M. Lala, “tentative post-war plans of development of our own, which included…the operation of external services westwards and, if possible, all the way to England.”

Soon after the war ended, Mr. Tata set about putting these plans into motion, renaming his company Air India, taking it public and hiring a former TWA stewardess to train his new flight attendants. In 1948, shortly before Air India launched its Bombay-London route, Mr. Tata agreed to allow the new Indian government to own 49 percent of the airline, with the option to buy another 2 percent whenever it desired. The arrangement was, in retrospect, an odd one, for in giving the government the chance to become the majority shareholder, it opened the door to the nationalization of the airline. And yet Mr. Tata had, in 1946, told the Associated Press of India: “In the present instance…there is an overwhelming case against the nationalisation of Indian airlines.”

Almost inevitably, in 1953, the government paid 28 million rupees to purchase the rest of Air India’s stock; for another 30 million rupees, it also purchased eight other domestic airlines. Mr. Tata was disconsolate. In his biography of Mr. Tata, “Beyond the Last Blue Mountain,” Mr. Lala quotes him as telling colleagues: “I was so indignant at the manner in which the Government had treated the air transport industry…and had deliberately brought it to its knees, in order to acquire it for a song.” The previous year, he had already complained to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru that members of his cabinet were “resorting to incorrect and unfair statements…that the airlines in general, and Air India in particular, are dishonest and greedy, cannot be trusted, and fully deserve their present plight.” Mr. Nehru replied that his government had been “driven to the conclusion that there was no other way out except to organise [the airlines] together under the State.”

In a long, stinging telegram back to Mr. Nehru, Mr. Tata minced no words:

I CAN ONLY DEPLORE THAT SO VITAL A STEP SHOULD HAVE BEEN TAKEN WITHOUT GIVING US A PROPER HEARING

The pain of having his airline snatched away in this manner never entirely dissipated. In a letter to a colleague, Mr. Tata wrote:

“Even more than the decision itself, I was upset by the manner in which nationalisation was introduced through the back door without any prior consultation of any kind with the industry… However, we have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that we are living in a political and bureaucratic age in which people like ourselves no longer count for much in the scheme of things.”

A most admirable coda followed. Having taken possession of his airline, the government concluded that the best person to guide Air India was Mr. Tata himself, and it invited him back to be its chairman. This presented a quandary, and Mr. Tata canvassed the opinions of his top managers before he made his decision and took the job. “I came to the conclusion,” Morgan Witzel quotes Mr. Tata as saying in his book “Tata: The Evolution of a Corporate Brand,” “that I should not shirk the opportunity of discharging a duty to the country and to Indian aviation. I am particularly anxious that the present high standards of Air India International should not be adversely affected by nationalization.”

In a final message to the Air India staff that summer of 1953, before he lost ownership of his airline, Mr. Tata wrote:

“So as this last day of July marks the passing of an enterprise born twenty-one years ago, my thoughts turn to happier days gone by and in particular to an exciting October dawn, when a Puss Moth and I soared joyfully from Karachi.”

This is the second of a two-part series, in honor of Air India’s 80th birthday, which is October 15. Read part one about the airline’s birth