Let alone India’s first cotton mill, first steel plant and first institute for fundamental research in science, we have Parsi Theatre to thank for the musical routines of Bollywood!

by Amulya B June 20, 2017, 5:57 pm

In the last few years, the world has been grappling with the refugee crisis. The innovations in technology has made the whole experience of witnessing a crisis very visceral and we hadn’t encountered a crisis of this scale since World War II.

However, it is undeniable that human history is centred around victories and conquering lands. And the present may not be too different — people losing lives or being displaced from their homelands.

In India, the distinct Parsi Community might now be part of the colourful fabric of minorities stitched together, but they were once refugees too, who much like today’s Syrians, fled their homeland on boats and ships. After the fall of the Sassanian Empire (which had endorsed Zoroastrianism as the state religion) in Iran in 642 CE to Arab Muslims, a group of Zoroastrians sought refuge from religious persecution in the western shores of India.

This Zoroastrian group, which sailed from the Pars region of Iran to today’s Gujarat, is known as Parsis.

Parsi Woman and Son, 1900/WIKICOMMONS

According to Qissa-i-Sanjan (Story of Sanjan), a 16th century lore on the life of the early Zoroastrian settlers in India, when the refugees first arrived on the shores of Sanjan, they were presented with a full glass of milk by the local ruler Jadi Rana. It was a metaphor conveying the message that there was no space for the newcomers. It was then that the Zoroastrians responded by adding a spoonful of sugar to the milk, demonstrating that they would be ‘like sugar in a full cup of milk, adding sweetness but not causing it to overflow’.

They were allowed to live and follow their religion after agreeing to a few of Jadi Rana’s conditions: they would explain their religion to him, they would learn the local language, the women would wear sarees and they would conduct weddings after sunset. This “selective assimilation”, as termed by Harvard Pluralism Project, is what led to the distinctiveness of Parsis from their Zoroastrian counterparts who stayed back in Iran.

You may also like: An Indian Designer Has Developed a Unique Shelter for Refugees Worldwide

These remaining Zoroastrians started arriving on the familiar shores of Western India during the 19th century, and are today known as Iranis. To reiterate, they too are Zoroastrians like the Parsis, but are culturally, socially and linguistically distinctive from them.

The qissa of Zoroastrians demonstrate mainly two things: The Indian subcontinent always opened its doors to people from the world and religions survive only when they adapt to the demands of the epoch. Religion, much like any cultural practice, must always be open to change, if it has to survive. However, that does not mean you have to give up your own culture and identity. The ‘selective assimilation’ of the Parsis exhibited integration into a host country while holding on to the distinctiveness.

Though the Zoroastrian community seems to take the Story of Sajan lore at face value, there have been numerous debates regarding the authenticity of its content since it has been written based on oral tradition, centuries after their arrival. However, the lore is important in understanding how Parsis themselves saw their arrival and settlement in a foreign land.

Nevertheless, it is indisputable that both distinct groups of Zoroastrians who arrived at two different moments in history of India were never turned back. Today, the community, though very small and living amid the fear of dwindling numbers, has a special place. This is the community that gave us freedom fighters like Dadabhai Naoroji and Bhikaiji Cama, a visionary like Jamsetji Tata, nuclear physicist like Homi J Bhabha, and advocates like Fali Nariman. In fact, despite representing less than 0.6% of the Indian population, Parsis have helmed all three defence wings of the Indian Armed Forces. Let alone India’s first cotton mill, first steel plant and first institute for fundamental research in science, we even have Parsi Theatre to thank for the musical routines of Bollywood!

All these achievements could be included in the pages of Indian history because a local ruler of Gujarat did not close his doors to a shipload of refugees, but welcomed them home.

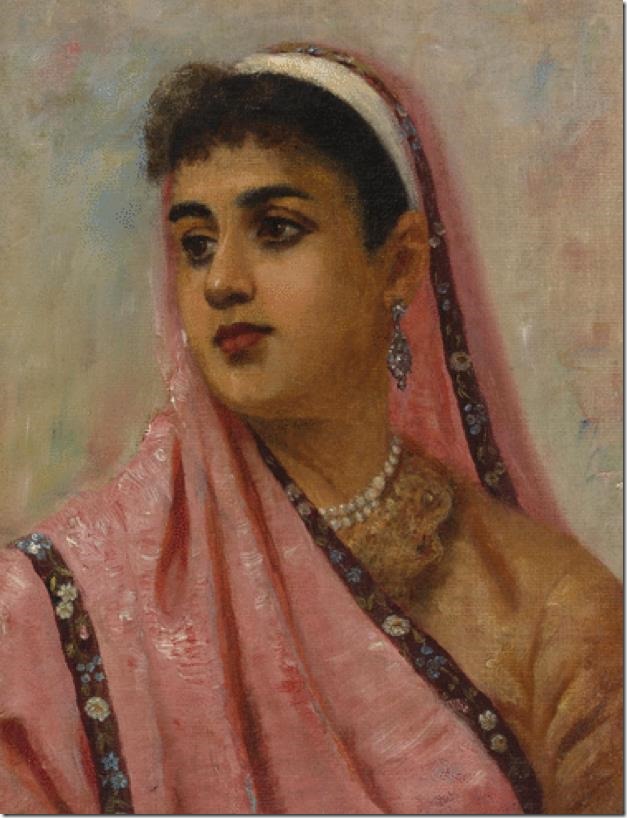

A Parsi woman in the eyes of Raja Ravi Varma/ WIKICOMMONS

The nation-state of India has a different story to tell. We haven’t been a signatory to 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention nor its 1967 Protocol. Though the reason for this is not known publicly, it is speculated that since the borders of South Asia are extremely porous, any small disturbance can upset the demographics and infrastructure of a nation that is indeed poor by global standards. Yet, despite being a non-signatory, India has been hosting refugees from Tibet to Sri Lanka.

However, it is important to note that global refugee crisis has its roots in the apparatus of nation-state and colonial era borders, whose continued relevance is exacerbating the situation. It is essential to remember that borders are man-made. The least one can do is offer compassion to refugees instead of contempt. After all, refugees of today are citizens of tomorrow.