Debates over the Uniform Civil Code usually zero in on one kind of personal law: Muslim matrimonial law. What gets less airtime is Parsi matrimonial law. We assume that it lacks the gender asymmetries of Muslim personal law. There is a long history of Parsis being held up as a model minority, by implied contrast with Muslims. This narrative was at its heyday under British rule. It is enjoying a revival in Modi’s India.

Article by Mitra Sharafi | Times of India

Take the prohibition of Parsi polygamy in 1865. In the 1850s and 60s, elite male Parsis in Bombay drafted the text of what would become Parsi personal law, including the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act of 1865. The centrepiece of this statute was the invalidation of polygamous Parsi marriages.

Parsi elites made a lot of the fact that their own community had initiated this reform. The honorary secretary of the Parsi Law Association that drafted the statute, SS Bengalee, declared that the Parsis were Asia’s most civilised people for voluntarily giving up polygamy . Sixty years later, a Parsi lawyer named C. F . G. Chinoy called the statute “the Magna Carta of the rights and privileges of woman.”

These celebratory accounts failed to mention that another male privilege – the right to have sex with prostitutes -was stealthily protected in the 1865 Act. Under English law, adultery by a husband was defined as the act of sexual intercourse with any woman not his wife, including a prostitute. In the Parsi Act, the definition of adultery excluded sex with prostitutes. For the next seven decades, Parsi wives could not prove that their husbands had been adulterous if the men had sex with prostitutes.

The prostitution exception was eliminated in the 1930s, when the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act of 1936 became law. This reform was celebrated for its gender equality, as was the statute’s creation of uniform grounds for divorce between husbands and wives.

As in 1865, though, the new statute smuggled in another change that was bad for women. While Parsi men gave up their right to have sex with pros titutes in the 1936 statute, they fortified their right to beat their wives.

Under the 1936 Act, one Parsi spouse could file for divorce if she suffered from “grievous hurt” inflicted by the other. The 1865 Act had been vague on domestic violence, and Parsi draftsmen in the 1930s took the opportunity to clarify. What ensued was the most precise and public discussion of Parsi matrimonial violence of the colonial period, and possibly ever. Early versions of the 1936 bill had imported the Indian Penal Code’s definition of grievous hurt. Had this text been adopted, a criminal conviction for grievous hurt could have served as the basis for a divorce suit. But organisations like the Dadar-Matunga Zoroastrian Association, the Zoroastrian Brotherhood, and the Grant Road Parsi Association objected.

As the Parsi newspaper, Jam-e-Jamshed, put it: “Having experience as worldly men, that husbands are rather too free with their hands…would it be safe to dissolve marriage at every violent quarrel between a husband and wife?” These voices prevailed. The fracture or dislocation of a bone or tooth would not constitute grievous harm in Parsi matrimonial law, although it would continue to be a crime. Any injury that caused the wife to be in “severe bodily pain” for twenty days or unable to follow her ordinary pursuits would also not constitute a ground for divorce. The message was clear: forms of violence that constituted criminal offences were not serious enough to be part of Parsi wives’ divorce suits.

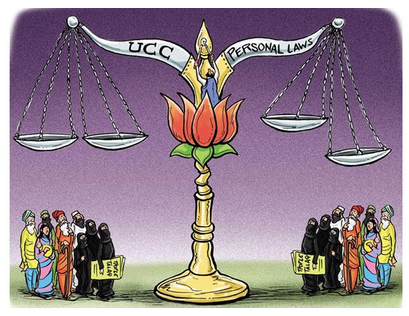

The characterization of Parsi matrimonial law as a model personal law overlooks the troubling tradeoffs made in Parsi legal history. Some products of this history , like the matrimonial definition of grievous hurt, remain with us today. Conversations about the UCC should look beyond Muslim matrimonial law to consider the fraught history of other bodies of personal law, too. (The writer is associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and author of Law and Identity in Colonial South Asia: Parsi Legal Culture, 1772-1947)