Two months before I was to leave Bombay for Toronto, a friend from St, Xavier s College asked to borrow my copy of "A Hard Days Night,"

Empire Records

Something Borrowed by Rohinton Mistry / The New Yorker october 11, 2010

My friend—I’ll call him Harish—was agreeable company, always trying to find hidden meanings in a song, parsing, analyzing as though it were Wittgenstein or Schopenhauer. When B. B. King moaned that his woman had done him wrong, Harish was happy to spend an afternoon debating what the bluesman and his guitar were actually saying and feeling.

I loaned him the LP; it was 1975, the country was in turmoil, and Iris request barely registered. In the hundreds of thousands, people were marching daily against misrule and corruption. Newspapers wrote, before censorship silenced them, about dissidents and union leaders disappearing, broken bodies found by suburban railway tracks. The Prime Ministers declaration of a State of Emergency was barely a month away. Changes in my personal life, though less drastic, were no less unsettling. My immigration visa had arrived. This was the moment that our middle-class uves were spent preparing for, encouraged from childhood, as we were, by parents, friends, teachers—the generations that had borrowed, and borrowed from, the culture of the colonizer, who had made the loan seem a gift, seductive, pain-free. In tine, we came to believe it was our birthright, our own culture—flowery frocks and Enid Blyton and all.

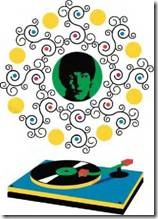

The road that led me to "A Hard Day’s Night" stretched back to my father s 78 r.p.m.s. His large collection of shellac pressings was made up of things like Gilbert and Sullivan operettas; the London Philharmonic with Brahms’s Hungarian Dances; and a medley of English pub songs, including "Down at the Old Bull and Bush.* Though I didn’t hear a sitar performance until many years later, and that only when Ravi Shankar was George Harrison’s guest at the Concert for Bangladesh, as a child 1 could sing all the words to "Don’t Fence Me ln. The electric Garrard gramophone that spun these records was my father’s proudest possession. Everything he did—dusting the rosewood cabinet, cleaning the tonearm and needle, selecting a record, switching on the turntable—

had an air of ritual homage, as though in a temple. I liked to sit close to the gramophone, where I could watch the record spinning, because the grooves in die shiny shellac appeared to create an endless spiral that almost induced a trance, making visible the passage of time. Suddenly, eternity was not an idea that evaded grasping but music that played forever.

When at last we could afford a modem multispeed turntable, it was not much of a detour to 45 r.p.m.s and Li’s: to Cliff Richard’s Herman’s Hermits, the Beatles and the rest. Good, mediocre, or appalling, we embraced it all, as though it had sprung from the soil of our South Bombay neighborhood. If it had a "Made Somewhere in the West" tag, it was superior. Elvis’s sideburns, pointed shoes, and tight pants excluded almost everything Indian from our lives, so skillfully that we were forever oblivious of that sleight of hand.

But borrowing requires reimbursement: the lender always comes calling. And the loan masquerading as the colonizers gift would be repaid in emigrant sons and daughters, raised to believe that this ancient country was futureless, the only solution to settle in the West, to make a better life.

Even though my LPs were not going with me, the one Harish had borrowed kept nagging at me. I wanted to have the album in its slot before 1 left, in die box I had fashioned out of plywood and corrugated cardboard to hold the small collection.

My departure was less than a week away when I reminded him of the LP. 1 le was not yet done with it, he said. It would have felt churlish to press harder, and we parted, as usual, with a joke, a laugh, he wishing me bon voyage, as though I were off on a short holiday.

While exchanging my life, my country, for one that I had never seen and knew almost nothing about, 1 clung to that record- Pursuit of the LP continued in my first letters from Toronto. Such concern, from ten thousand miles away, must have struck my family as odd. But 1 was far too sophisticated to admit to homesickness, and, eventually, 1 gave up, unable to explain my inordinate attachment

In my mind, however, the LP remained, the thought of it, spinning endlessly, and its corollaries: couldn’t go home, couldn’t leave home. 1 low to make sense of these two?

in time, the answer began to crystallize. In die space between the two, where the paradox resides, the idea of home could be built, anew, with memory and imagination, scaffolded by language. The LP no longer mattered.

Sometimes, a delinquent loan is a blessing realized.