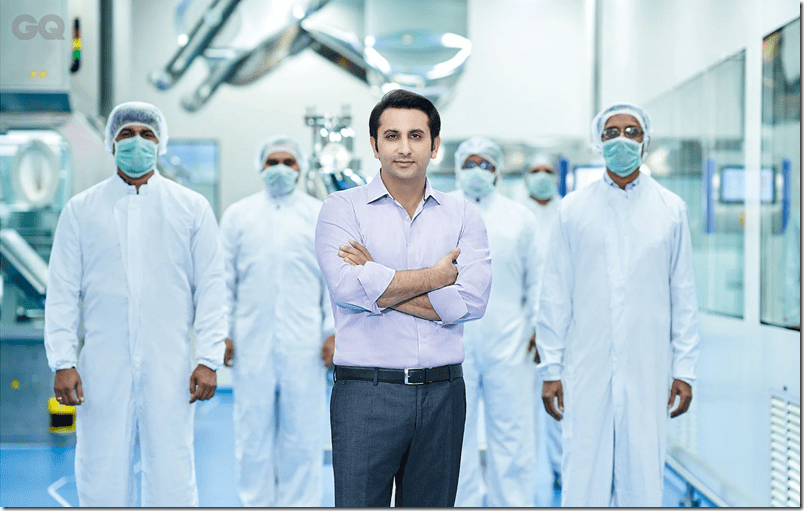

Any other summer, Adar Poonawalla would’ve been aboard a yacht on the French Riviera. But Covid-19 upended all plans, and the CEO of the world’s largest vaccine company finds himself in the thick of the action

Article by Che Kurrien | GQ India

Few news stories today are being tracked with greater fervour across the globe than the race for a Covid-19 vaccine. And the privately held Serum Institute of India, the largest manufacturer of vaccines in the world by volume, is central to many of these conversations. On April 22, with the world reeling under lockdown gloom, the company’s 39-year-old CEO, Adar Poonawalla, announced an exciting partnership with Oxford University’s renowned Jenner Institute, which was about to start human clinical trials on its promising single-dose vaccine candidate; if all goes as planned, it would have approvals by September. Given the urgent need for a vaccine that’s available at mass scale, Poonawalla declared he would take the financial risk and manufacture millions of doses of the Oxford candidate ahead of approvals; when the approvals come in – which he is confident they will – he would be ready with abundant inventory that people could take immediately; if approvals don’t come through, he would take the financial hit on the useless stock.

Business risks notwithstanding, the stockpiling of vaccine inventory has been a tested strategy for the Serum Institute, founded by Adar’s brilliant, maverick father, Cyrus, in 1966. Cyrus realised it was advantageous to produce and store low-cost vaccines at scale even though there were no immediate orders – so he could deploy his inventory at short notice as soon as there was an outbreak anywhere in the world. Over time, the Serum Institute, located in the historic, fast-growing city of Pune, became a trusted partner to organisations such as the World Health Organization, UNICEF and the Gates Foundation. It also made the Poonawallas one of India’s wealthiest families, worth about $11 billion today. The Poonawallas first made their name as India’s leading horse breeders and owners, with a reputation for glamour and the good life, including a penchant for limousines and aircraft. The Serum Institute, too, owes its start to the family’s racing background: As breeders, the Poonawallas used to sell their older stock of horses to the venerable Haffkine Institute located in Mumbai, which required horse sera for its vaccine production. One of Haffkine’s doctors gave the young, ambitious Cyrus a business idea: Since he owned the horses and had abundant land, Cyrus should move up the value chain and start his own processing plant. The Serum Institute of India was born. The rest is history.

In preparation to run the family business, Adar Poonawalla was trained in England, and took over as CEO in 2011. He has since enhanced the company’s product line, expanded its global footprint and struck numerous partnerships with drug developers across the world. In 2016, Poonawalla announced an investment of `100 crore ($13 million) towards a Clean City Movement, a public-private partnership that aided waste removal across Pune. This civic intervention was widely praised, and he was recognised with a GQ Men of the Year Award for Philanthropy.

That seems like a lifetime ago. As the following interview, conducted recently over Zoom, suggests, every ounce of his energy at the moment is being directed towards the one vaccine the entire planet is waiting for.

Did you ever foresee that the planet would be in the throes of a global pandemic caused by a novel coronavirus?

Bill Gates is my mentor, and I’ve been hearing him talk about this scenario since 2015. That it’s perhaps not nuclear war we should be worried about but a global pandemic like the one we’re living through. So, I wasn’t surprised when it happened.

Today we have a deeply integrated global transport system that connects people from far-flung corners of the Earth at great volume and speed; there’s also the growing prevalence of zoonotic viruses caused by climate change; and the increased contact between humans and animals, as we push deeper into their territory. Yet, despite all the warnings and signs, we ignored smart people like Bill Gates and did nothing.

Given that you took Gates seriously, how did you prepare for this scenario?

I’ve been focussed on building tremendous capacities to produce vaccines. Which is why I’m one of the front runners today [to manufacture the Covid-19 vaccine], while others are going to take two or three years to scale up production. I understood what Gates as well as other scientists and epidemiologists were saying. A global pandemic like this was bound to happen – it was only a matter of time. And over the next few decades, we’re likely to see even worse outbreaks. Luckily, Covid-19 has not been as deadly as we initially thought. But it is a stern wake-up call. It was inconceivable that public health would become such a central issue.

It will have to be taken very seriously now. The country will have to build more hospitals, better health surveillance systems and improve testing. We’ve discovered there aren’t enough beds, quarantine zones or comprehensive health insurance policies. We’re going to see a dramatic improvement in all these areas. Countries usually spend money on arms and defence systems – these are how states have traditionally allocated their resources, instead of investing enough in healthcare and education. I expect priorities will change now, which is one positive outcome of this crisis. As a society, we need to double down on all the things we’ve recently learnt – about nutrition, hygiene and healthcare. And build from there.

Media across the world is suddenly very interested in you. How do you feel about all the attention?

I never asked for it, and it’s really because of the critical work we’re doing. People are curious about our progress. Whether it’s this year or the next, we will have a vaccine. Having said that, I’ve tried to caution the media to manage their expectations. But one also has a huge sense of pride in being an Indian given what we’ve already achieved: 70 per cent of the world’s vaccines are made by Indian companies. And it feels great to be recognised as a company that’s producing products that protect lives. In terms of public perception, we’ve been known more for our lifestyle; now people understand the work we do. I’m grateful for that.

How are you handling the pressure?

Initially, I was a bit overwhelmed, but I’ve taken it all positively. Even the so-called controversial media platforms have treated me with love. Nobody is looking for a “gotcha” moment. That’s made me comfortable. I do feel a huge sense of responsibility when I get into bed each night. I’m constantly playing back the day to see if I missed something. Should I partner with some company? Do I have enough glass vials? Is there a technical issue that needs to be solved? Because our operation is complex with so many moving parts. I don’t want to just have the vaccine and miss some small yet crucial logistical detail that prevents us from getting it to market. You could say I’m in a heightened state of alert these days. I’ve never been under this amount of pressure to perform before: I’ve just been a businessman who’s gone about doing my work, while enjoying and living my life.

The race for a vaccine is being tracked around the clock. And you have partnerships in place with a few key developers. Which ones are you most excited about?

I’d be delighted if any vaccine candidate being developed across the world succeeds, because that’s the need of the hour. Naturally, I’d be a little more excited if it were one of ours. Normally, a vaccine takes about four or five years before it’s approved. What’s exciting with the Oxford candidate is that it’s already undergoing human trials in the UK, and if all goes well, we can manufacture it very quickly. There’s an 80 per cent chance it will succeed by the end of this year. At that point, we will be ready with millions of doses to give our countrymen, as well as to some other countries.

My other partnerships are going to take slightly longer to fructify, about two years or so. But I’m equally excited about these. I’m working with an American company, Codagenix, on a live attenuated vaccine. These types of vaccines have historically had the best efficacy, provided long-term cover, as well as broad-based protection. Yet, in the short term, I’m really excited about the Oxford candidate and that’s the one we’re going to start manufacturing within a month.

You will start manufacturing this vaccine in June?

Yes, we will start manufacturing sometime in June and stockpile it. But, let me clarify: we’re not giving it to anyone till November or December, when we’re certain that the safety and efficacy has been clearly proven. Apart from the trials in the UK, we’re also going to do a clinical trial in India, which we will start in a month. We want to evaluate safety and efficacy here, under local conditions, working with a set of hospitals in Pune and Mumbai, and a few thousand patients. We want to be fully confident, and not rush anything. By the time the results of the human trials in the UK are available, we will also have results from India to review.

With over 100 vaccine candidates in the race, it must be an emotional rollercoaster.

My experience tells me that 85 per cent are going to fail. Most are based on far-fetched concepts that have never been proven; experimental processes and technologies that are going to be very hard to manufacture and scale up. Which leaves about 15 candidates that have a shot at success. As a manufacturer, I welcome them all. Because ultimately, they have to come to someone like me to create large quantities of their vaccine. The companies who are developing these products have got excellent scientists and research capabilities. What they don’t have is the ability to manufacture at scale and at a reasonable price. Today, there are five or six companies in the world who can do it. Apart from these, there are three or four companies in China who could also do it; yet, given the situation, people are going to be cautious about doing it there.

India manufactures most of the world’s vaccines. This comes as a surprise to most people.

The total market for these vaccines is less than $2 billion, as they’re affordably priced. That’s why it’s not really caught many people’s attention. For Wall Street, these figures are peanuts; yet today, when our lives and livelihoods are at stake, people are suddenly very curious about vaccines, about how the business works, as well as about who makes them. There’s a lot more clarity about this now, and India is being recognised for being at the forefront of the industry.

Is the skepticism from certain quarters surrounding vaccines a thing of the past?

Vaccines are based on science. There’s now an almost universal acknowledgment that science is supreme.

Is suspicion about Made-in-India vaccines a thing of the past?

They don’t say it, but I feel it, and all the other Indian companies feel it. Yet, this is because of the lobbying done by Big Pharma, who want to keep us out because we beat them on price. So they raise questions about quality and reputation. The quality of our products is the same as those made in Europe and the US.

As a private company, you answer to no one but yourself and can make truly independent decisions. Yet, when a relatively new drug discovery company’s stock surges from $18 to $90, do you wonder what it would mean to be that liquid?

Do I feel bad? Sometimes. If I were listed, I’d have billions of dollars thrown at me. But then reality dawns, and I remember how public companies are accountable to investors, and pressured into making decisions driven by quarter-on-quarter growth and performance. I don’t want that – perhaps I’m not ready for it yet. I wouldn’t be able to make decisions like the one I’ve just made: Shutting down and sacrificing internal facilities to make room for the manufacture of a Covid vaccine that hasn’t been proven yet. And, that’s the kind of independence as a business I would like to retain.

What are your plans for Serum Institute in the future?

To develop and produce even more vaccines and monoclonals. For example, I have a cure for dengue, which we will probably launch at the end of this year. Nobody has this in the world. So far there’s one dengue vaccine. But there’s no monoclonal cure that you can take when you’re in the hospital. This is something a patient can be given over two or three days, and be cured. The clinical trials are underway as we speak, and we have many exciting products coming up over the next few years. Though we’re already in 165 countries, I will also expand our global reach: pushing into Europe and the United States – markets that we’ve never been able to enter as we’ve been blocked by Big Pharma. These are the new and final frontiers. Yet, we will do it slowly, not taking on more than we can chew.

How are you relaxing these days?

[Laughs] I’m not relaxing much really. I’ve moved to my farmhouse, which is on 200 acres of land outside the city, where my horses are. It’s close to my office. We recently constructed some lovely villas on the land. I’ve been spending time with my family, riding my horses a little, swimming and enjoying the nature around me.

Your office is a refurbished A320 aircraft. Are you an aviation fan?

It has my personal chambers, conference rooms, bathrooms – everything a private A320 would have. It’s permanently stationed in the new office campus I’ve just built. I can’t say I’m an aviation fan, but I do enjoy the comfort and convenience my jets provide, allowing me to avoid the chaos and delays at airports, especially given the amount of international travel I do. The newer long-range jets have been a game-changer: I get on board on a Sunday night after dinner, go to sleep, wake up seven or eight hours later in Europe, do my meetings through the day and sometimes even fly back the same evening. It’s given me the ability to take a lot of trips I wouldn’t have otherwise, and resulted in sealing a lot of the partnerships we have in place today. That said, the lockdown has helped me discover that Zoom and Skype are wonderful too, and I’m going to travel a lot less in the future because that’s the new normal.

If we weren’t in the middle of a pandemic, where would you be at the moment?

In Cannes, on a yacht, sailing down the coast with my family, watching the Grand Prix, attending the film festival and spending time with friends there. The weather is great this time of the year. I suppose I’m a little sad we’re not there at the moment. But the excitement and joy that comes with what I’m doing right now more than compensates. This really is a once-in-a lifetime opportunity.