How did medieval Zoroastrians imagine the family of Zoroaster, the founding figure of their religion?

Unlike founders of many other religions about whose time and place we can reach a certain degree of certitude, there has been and still is much scholarly debate over the time, place and even the historicity or otherwise of Zoroaster. The same uncertainty applies to the facts about his family life. What I intend to do in this blog is rather to demonstrate how interpretations of certain aspects of his domestic life story changed throughout time and place based on current social realities and ideals of his followers. The two selected cases that I would like to address here are from late antique-early Islamic Zoroastrians and modern Parsis (i.e. descendants of those early medieval Zoroastrian migrants to the shores of Gujarat in western India).

Article by Kiyan Foroutan | leidenmedievalistsblog

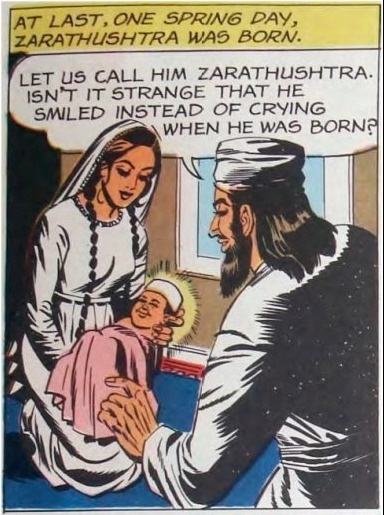

It should be pointed out that not all aspects of Zoroaster’s traditional biography were subject to change. Certain essential features of his legend persisted long among his followers – in many cases till today – such as his laughing at birth (instead of crying); the conversion of his patron Kavi Vīštāspa and his entourage into his religion and so forth. When it comes to his parents, clan, family and children, one should distinguish between the elements which might have been formed, evolved and maintained a long time ago and those clearly novel elements about his family life.

The birth of Zoroaster. From Bachi Karkaria’s Zarathushtra (1974). Public domain, available online at http://archive.org/details/zarathushtra, accessed 3 January, 2021.

The birth of Zoroaster. From Bachi Karkaria’s Zarathushtra (1974). Public domain, available online at http://archive.org/details/zarathushtra, accessed 3 January, 2021.

Scattered pieces of evidence about legends of Zoroaster’s life can be gleaned from Avestan texts. Extensive, systematic biographies of him exist in much later works in Middle and New Persian languages only. In addition to these, we can find information about particular episodes of his life in other Middle Persian texts as well. Taken together, they provide us with ample information about his clan, parents, eschatological sons and a little less about the (nuclear) family he himself formed. Apart from his three miraculously born sons-cum-future saviors, it appears that his wives and naturally-born children do not play a very significant role in the most complete narrations of his life and deeds, epitomized in the Middle Persian (Pahlavi) Denkard VII and Selections of Zādspram and the Persian Zarātoštnāma. However, there is a passage in Bundahišn, a Pahlavi text on the world’s origin redacted sometime between the ninth and twelfth century CE, offering us a vue d’ensemble of his family.

Zoroaster’s Family in Late Sasanian and early Islamic Period

In a chapter devoted to the genealogies of religious and legendary heroes of the Zoroastrian tradition in Bundahišn, Zoroaster’s family members are enumerated:

From Zoroaster three sons and three daughters were born. One was Isadwāstar, one was Urwatadnar and the other Wōrūčihr. Isadwāstar was the priest and the head of the priesthood. He passed away in the hundredth year of the tradition. Urwatadnar was husbandman and the chief of the Jam-built shelter, which was beneath the earth. Wōrūčihr was warrior and the head of the army of Pēšōtan son of Wištāsp, who is lodged in Kangdiz. He [Zoroaster] had three daughters. Their names were Frēn, Srīt, and Purōčist. Urwatadnar and Wōrūčihr were form the auxiliary wife (zan īčagar) and the rest were from the principal wife (zan ī pādixšāy). From Isadwāstar, a son named Urwarwizag was born. They call him Urwiz ī Birādān and because he was from an auxiliary wife, then they appointed him to the trusteeship (stūrīh) of Isadwāstar. Thereupon three sons of Zoroaster as Ušēdar, Ušēdarmāh and Sōšyans were from Hwōwī.

The names and some elements of this passage are not unfamiliar in legends of Zoroaster’s life. Occasionally, we do find references to these names as members of Zoroaster’s family in various Avestan and Pahlavi texts. The names of the children and his only named wife, Hwōwī, are attested in several Avestan passages. The association of the three naturally-born sons – Isadwāstar, Urwatadnar, Wōrūčihr – with the three classes of society probably has considerable antiquity, as it is partially attested in Young Avestan texts. The miraculous birth of Ušēdar, Ušēdarmāh and Sōšyans by three maidens is also elaborated in a good number of Pahlavi texts.

What makes this passage new, however, is the marriage and succession institutions which have been employed to explain the exact relationship between these figures. The complex legal institutions related to family are attested since the late Sasanian period only. We know of these and their intricacies through the extant Zoroastrian legal texts such as Hazār Dādestān ‘Thousand Judgements’, a late Sasanian law-book. Pādixšāy denotes the most standard kind of marriage in which the wife and any resulting children benefit from full legal rights. They would inherit a fixed share from the husband/father’s inheritance. In turn, they had certain obligations such as inheriting the father/husband’s debts or the duty to perform ceremonies upon his death. Čagar refers to a type of marriage in which a woman (who could be a wife, sister, or daughter) related to a dead or living sonless man would marry another man in order to produce a legitimate male heir for the former. The children born of this kind of marriage had certain rights and obligations towards their legal father, but not towards the biological father. In later Zoroastrian literature, čagar simply refers to the legal status of a remarried widow. Stūrīh, often translated in the literature as intermediate successorship or trusteeship, is the technical term for a broad, complex succession institution in which a Zoroastrian man or woman, usually a relative, would marry in order to produce children for a sonless man. S/he had the role of the mediator between the man and his legal heir. Until the heir reached adulthood, the stūr had certain rights and responsibilities. In late medieval and early modern times, Stūrīh came very close in its function to the institution of adoption.

Returning to our narrative, Zoroaster was represented to have two pādixšāy wives, one Hwōwī and the other unnamed, and one čagar wife, again unnamed. The latter wife brought forth two čagar sons, Urwatadnar and Wōrūčihr. His son from the principal wife, Isadwāstar, was thought to have married a čagar wife only. In need of a legal son of his own, the son produced from his čagar wife, Urwarwizag, was appointed to play the role of stūr for Isadwāstar. In sum, while certain aspects of this priestly interpretation of Zoroaster’s familywere evidently formed in earlier times, the assumed marriages of Zoroaster and his son, Isadwāstar, projected the practice of late Sasanian/early Islamic forms of marriage and succession into these distant, revered figures.

With certain permutations, additions and deletions, this image of Zoroaster’s domestic life as found in the Bundahišn passage continued among late medieval and early modern Zoroastrians in Gujarat and Iran, at least in learned priestly traditions. A reworked Parsi version of the narrative is attested in chapter nineteenth of Wizīrgard ī Dēnīg, a neo-Pahlavi text often dismissed as a nineteenth century ‘forgery’, but probably composed slightly earlier in early modern Gujarat. In this version, the story was expanded to make it explicit that Zoroaster had three wives, and that all three were alive during his lifetime and outlived him. All three wives are named and the name of the former husband of Zoroaster’s čagar wife is mentioned too. The parts on Isadwāstar’s čagar wife and son are, however, omitted.

There is no indication that this tradition was opposed until the middle of the nineteenth century. It is only from then on that some Parsis begin to voice reservations about the ‘authenticity’ of this narrative.

Portrait of Zoroaster in a Parsi house. Photo by Kiyan Foroutan.

Zoroaster’s Family among Modern and Contemporary Parsi Communities

The Parsi Panchayat – a council consisting mainly of wealthy laity governing the internal affairs of Parsi community in British-ruled Bombay – attempted to ban polygyny among Parsi Zoroastrians in 1791. This development might have been due to the impact of western ideals of monogamy or the legal manifestation of an older tendency within Parsi communities. At any rate, this regulation might have prepared the ground for later reinterpretations of the tradition of the three wives of Zoroaster among Parsis. A law more definitive and attuned to British sensibilities was passed in 1865, which prohibited polygyny among Parsis and imposed harsher penalties for the practice.

The first known reaction to the tradition was from Dastur Minocherji Edalji Jamaspasana, when Dastur Peshutanji Behramji Sanjana, a member of a rival priestly family, published Wizīrgard ī Dēnīg in 1848. Jamaspasana accused the owner of the manuscript, Dastur Edalji Darabji Sanjana, who was the uncle of Dastur Peshutanji, of fabricating the passage on Zoroaster’s wives in order to satisfy one of his lay patrons’ wish, who wanted to take or had already taken a second wife while his first one was still alive. By this and other accusations, the whole Wizīrgard ī Dēnīg was identified as a forgery of Dastur Edalji. However, not all Parsi priests were against this tradition. The prolific Dastur Erachji Sohrabji Dastur Meherjirana could still write in his Gujarati catechism, Rehbar-e Dīn-e Jarthośtī, published in 1869:

Our prophet Zoroaster had two wives, one shahzan [principal wife] and the other a widow (chakarzan). The name of the shahzan was Havovi and that of the widow is not known. His two sons Urvatatnar and Khurshedcheher were born of the widow and the remaining children wereborn of the shahzan. So says the Bundahishn. From this we can see that one can marry a widow. (tr. Kotwal and Boyd)

But even this traditional priest seems to have changed his mind when he was writing the Persian equivalent of his Gujarati catechism, Forūgh-e Dīn addressed to Zoroastrian children. In a series of questions about Zoroaster’ life, one is dedicated to the question of Zoroaster’s alleged polygyny. He rejected the possibility that Zoroaster, as God’s prophet and someone concerned with other-worldly matters, might have had more than one wife.

Almost all Parsis of the twentieth century who wrote on these passages in Bundahišn and Wizīrgard ī Dēnīg have rejected this tradition as spurious and against the spirit of the ‘true’ Zoroastrianism. Instead, they argued that Zoroaster had only one wife during his lifetime. In his reading of Yasna 53 in 1913, the Parsi scholar Bahramgore T. Anklesaria would thus praise Zoroaster’s message of strict sexual morality and monogamy:

The benediction clearly shows the advantages of monogamous marriage in order to incite the marrying pair to preserve love and harmony in the home in his simple, unaffected words, too majestic in their simplicity. (1913, 2.1: 5)

More than anything else, his interpretation will inform us about the notoriety of polygyny and celebration of monogamy by colonial and post-colonial Parsis.

Conclusion

Having focused on a passage in the Bundahišn, I have highlighted the less salient familial aspect of Zoroaster’s biography in medieval time. Despite certain continuities in this narrative, his marriages have been modelled on the marriage institutions of late antique-early Islamic Zoroastrians. The nachleben of this story among modern Parsis was also discussed. Like some other controversial subjects, they disputed it and finally replaced it with monogamous Zoroaster.

Further Reading:

Domenico Agostini and S. Thrope, The Bundahišn, the Zoroastrian Book of Creation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

A.V. Williams Jackson, Zoroaster, the Prophet of Ancient Iran. New York: MacMillan, 1899.

Mitra Sharafi, Law and Identity in Colonial South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Daniel J. Sheffield, ‘The Wizirgerd ī Dēnīg and the Evil Spirit: Questions of Authenticity in Post-Classical Zoroastrianism.’ Bulletin of the Asia Institute 19 (2009): 181-189.

© Kiyan Foroutan and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kiyan Foroutan and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.