“Aapro Fali”, the Parsi Community’s Pride and the Constitutional Authority With a Twinkle in His Eye

Fali Nariman always had time for good causes, even for reporters looking for free advice.

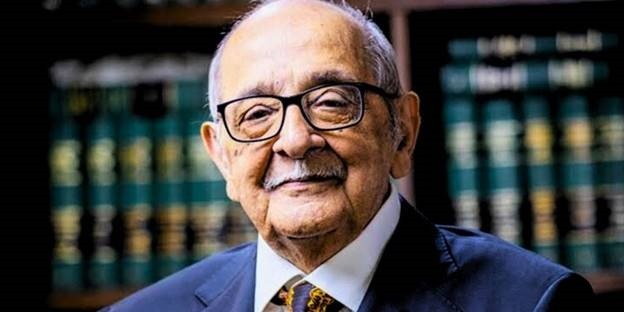

Fali Nariman (1929-2024). Photo: X/@RahulGandhi

Article by Bachi Karkaria | The Wire

We Parsis love to lay personal claim to our greats. Even all those with whom our familiarity doesn’t go beyond their public presence. In the case of ‘Apro George’ it was a legit claim; wasn’t King G. the Fifth once framed on our drawing room wall along with our forebears four generations up the family tree? But, seriously, the present hasn’t much replenished the trove of the past, which is why the community’s gaping hole grew wider with the passing of Fali Nariman, the last in that legion of India’s legal greats.

He wasn’t one of those who felt the need to add his voice to the cacophony triggered by any of the many issues, valid or hysteria-fanned which plague our increasingly paranoid community. But when called upon, he gave unstintingly of his time, erudition – and reputation. The most recent was that of the Bombay Parsi Punchayat vs the Union of India, where he steered an amicable solution to the emotionally sensitive matter of disposing of the corpses of Covid victims; the traditional manner was deemed violative of government protocols.

How deeply and as quietly he was invested in his own ‘court’ was reflected in the heartfelt tributes of the Delhi Parsi Anjuman and Parzor, Shernaz Cama’s UNESCO-recognised body for the preservation of Parsi-Zoroastrian heritage; he was its senior most patron. It recorded how much ‘Fali Uncle’ will be remembered for his ‘sane advice, his penetrating questions and his sense of humour’. It thanked him for all he had done not only for Parsis, but the Delhi Commonwealth Women’s Association, and in many silent charities both for ‘humanity and animals’.

Would it be too presumptuous for me to claim a personal familiarity? Yes, for the obvious reason that a mere hack must know her place vis a vis the Bhishma Pitamaha of jurisprudence. But then Fali himself kept his twinkling eye despite being the terror of those daring to take their muddying boots into the constitution’s sanctum sanctorum. He who wrote those magisterial books and op-eds wasn’t above emailing me an appreciative comment on a particularly clever turn of phrase – or, on his own bat, sending a letter to the editor validating a piece of mine which had argued against the excesses of our powerful Parsi orthodoxies.

It was because of these periodic back-pats that I made bold to ask if I could meet him in Delhi to understand the legal nuances of the Nanavati case for my book, In Hot Blood. My son was aghast at my ‘demanding free services of someone who charges such astronomical fees for a court appearance’ – and rolled his eyes while retreating in defeat when the great man wrote back to say, ‘Sure, come any time.’

So I betook myself armed with a tape recorder, notebook and questions prepared for a lengthy lesson on the judicial system and even constitutional law. After all this was a surreal case which began in the illicit privacy of an extra-marital bed and ended up shaking the nation’s certitudes. I needed the eminent jurist’s help in far more than understanding the parameters of ‘grave and sudden provocation’ cited by Commander Nanavati’s swashbuckling lawyers and dissed by staid judges of sessions and high court.

The case had put the last nail in the jury system’s coffin; split the legal establishment over the ‘unusual and unprecedented’ favours being granted to a man convicted of murder but with friends in high places (then defence minister Krishna Menon told a foreign correspondent, ‘I did not want the stain of turpitude to sully the reputation of a promising young naval officer’). It led to the summoning of a full bench of the Supreme Court to decide on how the Governor’s powers of pardon under Art 161 could be reconciled with the court’s constitutional mandate of supremacy under Art 142. Even then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was drawn into the legal maelstrom.

Also read: At a Time When the Battles of India’s Future Will Be Fought in its Courts, We Will Miss Fali Nariman

But as I settled down with pen and attention poised, Nariman simply handed me a fat dossier he’d already assembled. It contained copies of the relevant judgments that otherwise would have been herculean to access, as well as clippings on the Law Commission’s deliberations over ending the jury system (‘taken from Britain and transplanted on the soil of India’). The exhaustive file included Nariman’s speech to the Delhi Gymkhana on the then high-octane in the Jessica Lal case; it showed how despite a bar-room full of witnesses, no one had came forward to testify against the politically connected Manu Sharma – in contrast, no one had been in Prem Ahuja’s dressing room on that infamous late afternoon of April 27, 1959 except the dead victim and the cuckolded husband who’d gone there armed with a loaded Smith and Wesson.

Then, without any further reference, Nariman began chatting casually of matters unrelated, with that moustache-lurking smile. Of Bombay Parsi politics, but discreetly skirting Delhi’s larger one. With quiet pride in his son Rohinton not yet elevated to the Supreme Bench and his daughter Anahita, a paediatric psychological counsellor; with unabashed warmth of his grandchildren and great grandchildren.We talked of his daughter-in-law Sanaya, whose food scientist father shared the same name as my late ex-husband Jehangir, and her elegant mother, also a Bachi, with whom we spent wonderful mornings at their exotic-tree filled farmhouse in Golwad on weekend trips to our own, now-lost, chikoo orchard.

Mid-way Bapsi, his soul-mate and cookery-expert, joined us bearing a large tin of the Hyderabadi version of Irani-bakery khari biscuits. He was so manifestly attached to her, so caring of her during her long illness, that he refused my invitation to our Mumbai TOI litfest, because ‘My wife is too ill, and I need to be with her’. Something of him died too when she did in 2020. As the Parzor tribute to ‘Fali Uncle’ ended, ‘May you rest now with Bapsi Aunty in Garothan Behesht, and continue to bless us all.’

Bachi Karkaria is a veteran journalist, popular columnist and media trainer. Her best-selling books include Dare To Dream: The Life of Rai Bahadur M.S. Oberoi, In Hot Blood: The Nanavati Case That Shook India, Mumbai Masti with designer Krsna Mehta; Mills. Molls and Moolah, and Capture The Dream: The Many Lives of Captain C.P. Krishnan Nair.