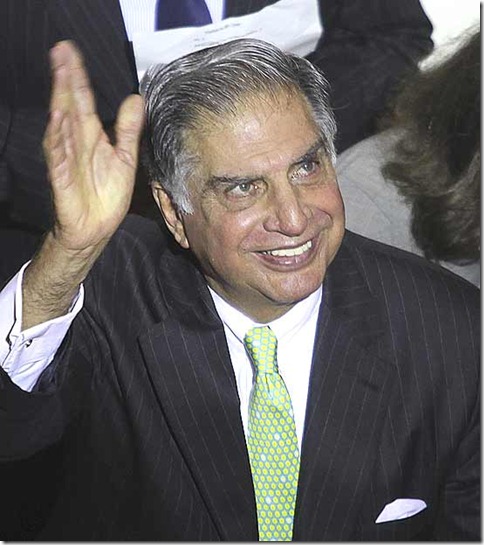

With just a fortnight to go for his retirement on December 28, Ratan Tata is getting ready for a new life. His multi-storey, sea-facing house opposite Mumbai’s Colaba Post Office is being reconstructed even as Mukesh Ambani has vacated the neighbourhood recently for a gleaming residential skyscraper. Tata, who plans to continue flying and return to formally learning music, will be surrounded by many objects of the 144-year-old, $100-billion Tata Group he’s led for the past 21 years. He can, of course, anytime walk down to the two Taj Hotels. But he’s unlikely to pop in at the New Persian Restaurant on Wodehouse Road where M.F. Husain had his morning cup of Tata Tetley.

By Arindam Mukherjee and Arti Sharma with Prachi Pinglay-Plumber

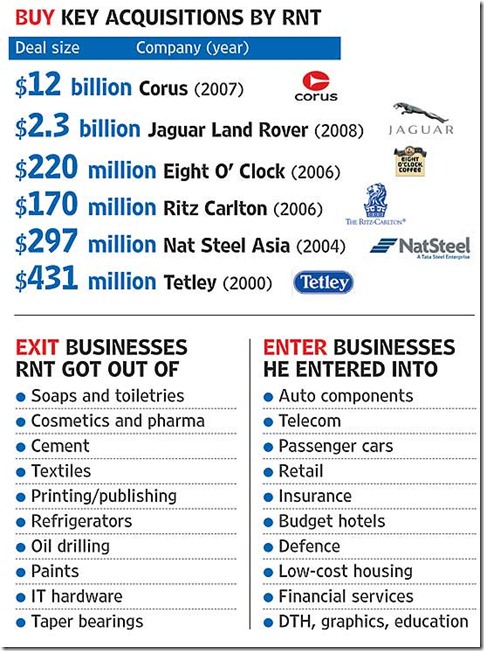

A short drive away in his Jaguar—and past thousands of Tata Indica taxis on the road—he’ll reach the outlet of the latest group venture, Tata Starbucks, near the Bombay Stock Exchange (where four Tata companies figure on the Sensex). Within walking distance is one of Tatas’ Westside retail stores, among the 10-odd new businesses the group got into under his stewardship. He could also stroll into his office in Bombay House. But Tata’s been insisting that, apart from his role as chairman of the all-powerful trusts that run the group, he is keen to move on. Like it happened with him two decades ago with uncle JRD, the burden of expectations will now have to rest on successor Cyrus Mistry.

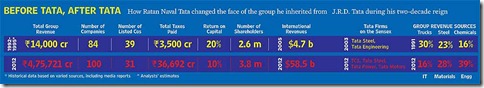

Not surprisingly—given the reverence accorded to the Tata brand—the 54-year-old Ratan Tata faced similar questions back then. It has been a remarkable transformation for a man who was pilloried for his initial directorship with radio and TV manufacturer Nelco in the 1980s. It’s to his credit that a sprawling, stodgy, loose confederation of companies run by individual chieftains went on to occupy a global stage (today, 56 per cent of revenues come from abroad). Along the way, he has courted controversies galore—including the publication of his conversations with his former lobbyist Niira Radia—that came to dull the saintly glimmer associated with the group (which did not speak to Outlook for this story).

It doesn’t help matters that this change of guard comes at a time when the Tata empire is creaking on many fronts. As per estimates, while the group as a whole has seen only about 10 per cent return on capital, a majority of its units have failed to achieve even that. The group depends heavily on two cash cows: TCS, the number one software company in India, and among the top globally; and Tata Motors, which, after its acquisition of Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), is showing good numbers. The group’s telecom venture has been losing money regularly, and others like Tata Steel are experiencing difficult times.

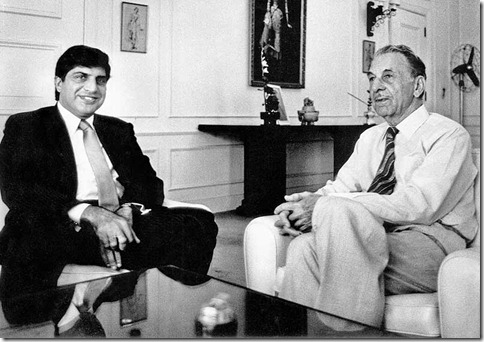

Tough times are what Ratan Tata faced too when he assumed reins in 1991, having to tackle JRD’s chieftains. The most prominent of these—enjoying unbridled freedom and enormous powers—were Russi Modi in Tisco (now Tata Steel), Ajit Kerkar in Indian Hotels and Darbari Seth in Tata Chemicals. Many of these companies were earning poorly. There was also little expansion in the group’s activities beyond existing businesses at a time when a liberalising India was opening up its doors. Says economist and Corporate and Economic Research Group chairperson Omkar Goswami, who has interacted with Tata for three decades, “At a time when Dhirubhai Ambani was moving with breathtaking speed and setting up new units, the Tata group was, by and large, staying where it was.”

Tata earned his spurs by dismantling these power centres. He also worked to increase the control of holding company Tata Sons to establish a central leadership and thinking. This was done using the cash generated by the group’s most successful company, TCS. That strategy paid off initially as the group got into a trajectory of high growth and diversified into areas like telecom and retail. “It’s a story of great consolidation where he got rid of business he didn’t want to be in, got rid of the satraps and got into a situation where execution became important and where he could leverage the Tata name,” says Goswami.

So as the Indian economy opened up and started growing, it was Ratan Tata’s dynamism that made all the difference to the group. Says Tarun Khanna, Jorge Paulo Lemann Professor at the Harvard Business School, “I’d attribute the group’s success to more than just the ambient economic growth of India, to a degree of entrepreneurial boldness (relatively scarcer in earlier years) and good management and stewardship.” Not everyone agrees, though, declaring that the group expanded without much synergy among group companies. Even now, says former telecom entrepreneur and Rajya Sabha MP Rajeev Chandrasekhar (who had a high-profile spat with Tata a couple of years ago), “The Tata group is currently at an inflection point because the days of large conglomerates are over.”

It’s ironical that with capital coming increasingly from overseas and non-Tata sources that group companies are facing questions regarding profitability. But that’s also because Tata took a conscious decision to go global with a vengeance in the late ’90s. In a paper, former OECD economist Andrea Goldstein has said that while the Tatas were always global—they had a London office in 1907 and Tata Steel made a light-armoured vehicle, called the Tatanagar because the steel came from there, during World War II—their international reach at the time was much smaller than that of other big Indian conglomerates like the Birlas, Thapars, Kirloskars, or the Oberoi hotel chain.

That changed dramatically when the group acquired Anglo-Dutch steelmaker Corus in 2007 for $12 billion. Within a year, ailing British carmaker Jaguar Land Rover was added to the kitty at a cost of $2.3 billion, a deal everyone thought was a mistake. Five years later, while the steel acquisition has hit new lows thanks to a dip in the sector, the car gamble has paid off, with JLR recording a 27 per cent jump in sales in the last fiscal. Have these acquisitions delivered shareholder value? Says Enam Securities co-founder and chairman Vallabh Bhansali, “Perha

ps in the process of globalisation, shareholder value has not got the imperative. Over the last few years, in terms of delivering shareholder value, Tata Steel/Corus has dragged numbers down.”

But you can’t fault Tata for dreaming big, even if the thought came riding a small car. After having practically started the ‘Indian’ passenger car segment with Indica, he came up with the idea of a Rs 1 lakh car, the Nano, a promise he delivered on, amidst worldwide sensation, in 2009. The product was an instant global hit, catapulting Tata to the league of people like Henry Ford. It’s a different thing that, three years down the line, the small wonder is struggling to survive against price increases and competition from global giants. In a recent interview on the Tata website (see below), Tata has said he’d love to have a chance to implement a new marketing plan for the car.

Another legacy Tata always sought to espouse was of his group’s distinctive corporate culture of honesty and integrity, which had to cope with the immense pressure of doing business in a fast-growing India. Says Anirudha Dutta of CLSA, “He achieved all this in an environment where political management, which the Tatas had always stayed away from, was becoming important and as a result Tatas were seen to be missing out on opportunities.” A case in point was Tata’s debacle in the aviation sector where rivals and politicians ensured his venture with Singapore Airlines never took off.

***

“I Have Always Tried To Do The Right Thing’’

In an interview posted briefly on the Tata website in December 2012, Ratan Tata was unusually candid. Excerpts:

On communication: “I have changed. I have realised you cannot carry people with you through public proclamations of what you want to do; there is a lot of behind-the-scenes convincing and cajoling that’s needed.”

On India Inc: “In my interactions with business leaders in India, as against elsewhere, there is this feeling that they are looking for cracks in your armour in order to pull you down; this happens not just to me but to everybody. There is a tendency to look at the dark side of everybody and everything, every situation and every government move.”

On Nano: “Unfortunately, it has come to be perceived as a low-priced car and various stigmas have been attached to it. It has been marketed like other cars, but as a minimal automobile at a low price. I think that is the wrong way to go and I would love to have a chance to implement a new marketing plan for the product, if that were possible.”

On failure: “In India, regrettably, hierarchy and designations are more important to people than job content or even pay packets…to that extent, I think we have failed—I have failed—in creating a flat organisation.”

On Cyrus Mistry: “I have watched him at close quarters, he possesses the ability to analyse businesses. I consider myself to be more of a numbers person than JRD was. I believe Cyrus is more of a numbers man than I am.”

On his future: “I would like to make a clean break.”

On his legacy: “I have always tried to do the right thing.”

***

Most prominently, during the days of the war between the GSM and CDMA lobbies in telecom, Tata took on the undisputed leader in Indian telecom, Sunil Mittal. He also had problems with ex-telecom minister Dayanidhi Maran with whom he clashed not just in the sector but also because the latter’s home company, Sun Direct, was a competitor to Tata’s DTH entity, Tata Sky. By 2008, the group found itself in the middle of the 2G scam, a charge it denied. More recently, the government initiated a probe into the VSNL disinvestment to Tatas in 2002.

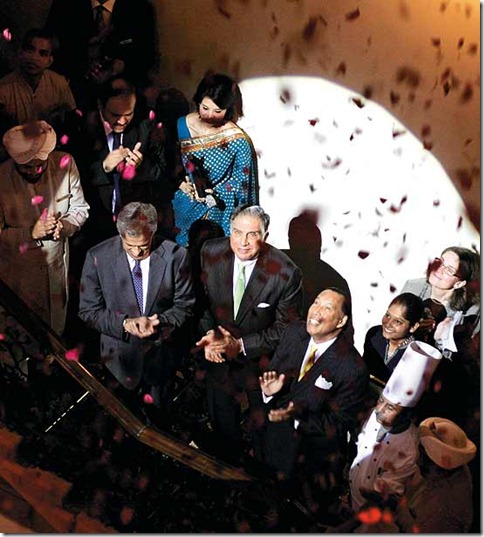

Of resurgence Tata with Taj Mahal Hotel’s staff at its reopening. (Photograph by Apoorva Salkade)

Many will say Tata needed to hire a lobbyist like Niira Radia in order to do business in India. Perhaps. But there’s no denying its fallout has dented the group’s clean image. “By and large, the Tata group has a clean image,” says senior business journalist and commentator Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, “but there are instances where the facade has worn thin. They are in business and clearly wooing politicians and while they are subtle and not doing it as brazenly as others, the fact is that there are grey areas here.” Many feel this could be because of India’s corrupt business environment. Says economist and former FICCI secretary general Rajiv Kumar, “There could be situations that are unavoidable. The operating environment may have necessitated even a company like the Tatas to behave in a certain way.” A view that prevails even outside business. Adds Santosh Desai, CEO, Futurebrands, “Over a period of time, he has absorbed political changes and some environmental compulsions may have rubbed off. It still is the most ethical group; it’s only in nuances that it may have gathered some taint in a few controversies.”

Whenever asked about his legacy, Tata has always maintained it is for others to judge. He has definitely taken the group forward and earned respect on the global stage. It’s unfair to judge him solely on the Corus acquisition and the high debt the group has collected. “Global competition from above and below is fiercer…. Mr Mistry’s central challenge: Find new growth norms in a slow growth world,” says management guru Vijay Govindarajan of the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth, US.

As for the image of the House of Tatas, Tata may have learnt how to navigate emerging India in a savvy manner, but the group’s reputation is still better than many of its peers. Having ably helmed the group for two decades, he is all set now to “be a grey eminence in the group and its affairs”, according to Goswami. Given that Mistry will need, at least initially, a helping hand in negotiating these troubled times, perhaps that walk down to RTI in Colaba for a pastry will have to wait for a bit.

On paper RNT’s letter to the DMK patriarch

The Controversies

Telecom: Tata Telecom was accused of being a beneficiary of the controversial dual-licence policy introduced by then telecom minister A. Raja in October 2007. Tata’s reputation took a beating when he wrote a letter to DMK supremo Karunanidhi in December 2007 praising Raja’s “rational, fair and action-oriented” leadership. Tata, however, was not named in the CBI chargesheet on the 2G scam—it was also discharged by the CAG.

Greenpeace ad

Niira Radia tapes: When Niira Radia’s phone conversations were made public by the media—including Outlook—they gave the impression of Tata trying to influence the appointment of A. Raja as telecom minister instead of Dayanidhi Maran in 2009. Tata moved the Supreme Court on grounds of privacy invasion. There was also considerable noise regarding the Tata group donating Rs 20 cror

e to a hospital in A. Raja’s constituency Perambalur and real estate transactions in Chennai. The Tata group denied the charges.

Bribery row: A couple of years ago, Ratan Tata said the group’s three attempts to launch an airline with Singapore Airlines failed because he was uncomfortable with the idea of paying a Rs 15 cr bribe to a minister, as an industrialist had suggested. Tata went on to state that “an individual thwarted our efforts to form the airlines”. The person being referred to is Naresh Goyal of Jet Airways.

Olive Ridley turtles: Dhamra Port Company Ltd (DPCL), comprising of Tata and Larsen & Toubro, was awarded a contract by the Orissa government to build and operate a port in Bhadrak district. But the project, which became operational in 2011, ran into troubled waters as it emerged that it posed a threat to Olive ridley turtles. Greenpeace issued ads against Tata in British papers, and its activists, dressed as turtles, even chained themselves to the firm’s Mumbai headquarters. Though operational, L&T is reportedly looking to find a buyer for its 50 per cent stake in DPCL. Tata has denied it has any similar plans.

ULFA Connection: Assam Police arrested several executives of Tata Tea in 1997, accusing them of aiding and abetting the banned insurgent group United Liberation Front of Asom or ULFA. This followed the arrest of the wife of an underground ULFA leader at Santa Cruz airport in Mumbai, whose treatment Tata Tea was paying for. The Tatas denied the charge and claimed it was part of their health scheme for people in Assam. Ratan Tata had met Assam chief minister Prafulla Mahanta to dispel misgivings. However, taped conversations of Nusli Wadia asking the central government to intervene mysteriously found their way to the public domain. Neither the PM at the time, I.K. Gujral, nor Mahanta, lasted long in office.