A master of light and play, with a blend of Impressionist and Cubist elements, Jehangir Sabavala’s blue-chip art has inspired a sense of wonder and awe. Akara Art’s latest show revives the late artist’s legacy

Article by Shaikh Ayaz | Architectural Digest India

PUBLISHED: NOV 04, 2020 | 09:30:19 IST

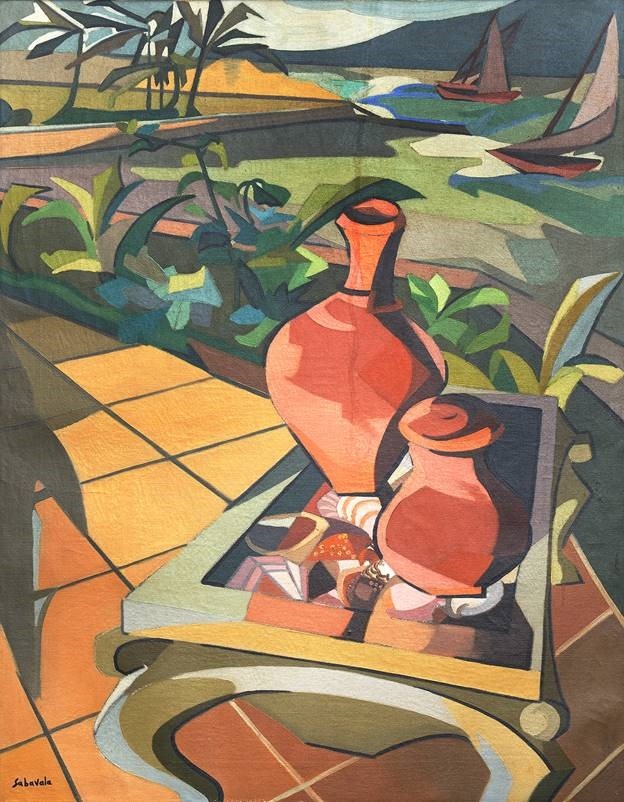

Jehangir Sabavala, The Miasmic Shore, Oil on Canvas 28 x 42 inches, 1967

Puneet Shah remembers only one brief encounter with the late Jehangir Sabavala who passed away in 2011 at 89, but he met the stylish artist’s equally elegant wife Shirin a couple of times. During one conversation, early on in the Akara Art founder’s career, she had suggested, “Why don’t you do a Sabavala exhibition at your gallery?” A decade later, the long-cherished dream has just come true with the opening of ‘Pilgrim Souls, Soaring Skies, Crystalline Seas.’ This is Mumbai-based Akara Art’s first major physical exhibition after the Covid-19 lockdown. Conceived during the sedate hours of the lockdown, Shah calls ‘Pilgrim Souls…’ “the most prominent show” of this kind, offering 15 works of art from different stages of Sabavala’s seven decades of work.

A Good Time for Sabavala

Sabavala was a subject of a prestigious retrospective in 2015 at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralaya that curator Ranjit Hoskote (also Sabavala’s official biographer) had dubbed an “introspective” for the sheer scale and intimate sweep that the show managed to achieve. By contrast, ‘Pilgrim Souls…’ is a smaller but sublime overview of the artist’s life and career. The city of Mumbai—the Parsi artist’s home and muse for decades—will see its first Sabavala show in five years. “Any time is a good time to have a Sabavala exhibition,” Puneet Shah offers. “He was not a prolific artist and to put together 15 paintings, most of them rare, is definitely an interesting proposition. There is a lot of interest in his work and much more in the recent past, both commercially and curatorially.”

2/2

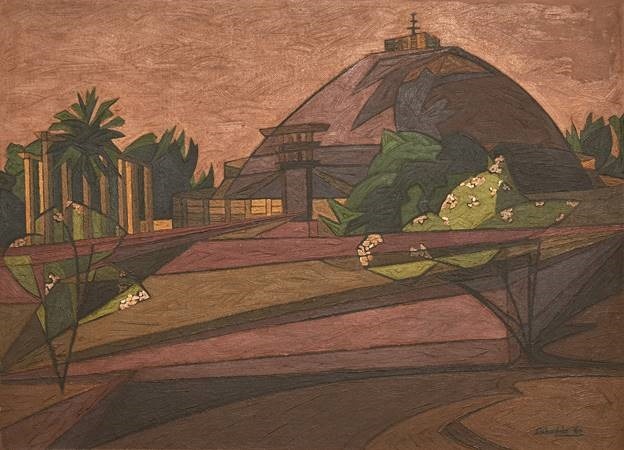

Sanchi, Oil on Board, 24 x 34

Mystery of Light

A viewer stepping into ‘Pilgrim Souls…’ will at once be immersed in Sabavala’s serene world, with spartan landscapes and vistas springing up on you. Are they a treatise on nature? Naturally-lit movie scenes? The artist’s monologue? Or harbours of intense solitude? None, perhaps because the artist was fascinated by the mystery of light, using his landscapes for which he was most famous to convey a sense of topographic beauty and bounty. “All artists across the 1960s and 1970s romanticised the play of light in their works, but Sabavala went much further to capture all its moods and nuances,” Shah says. The selection of paintings in ‘Pilgrim Souls…’ attest to his penchant for light, expanse and a deep study of the infinity of horizons and seashores. For example, in canvasses like ‘Beached Boats’ (1962), ‘The Miasmic Shore’ (1967), ‘Elegy’ (1967) and ‘The Shadowed Strand’ (1977), Sabavala allows light to permeate the surface to produce a mysterious shifting topography of translucent seas, opaque headlands and free-floating atmospheric forms. Also included in the exhibition is a wonderful watercolour of an Italian church that gives us a dekko into the artist’s preparatory travel diary. Ranjit Hoskote, who knew Sabavala well, says the artist enjoyed being in his studio but delighted in plein-air painting just as well, “setting up his palette in a piazza or on a beach, in Italy or France, and rendering what he saw around him—the architecture of churches or public buildings, the cascade of houses in a valley, the relationship between built form, social life, and nature—in vivid watercolour.”

2/2

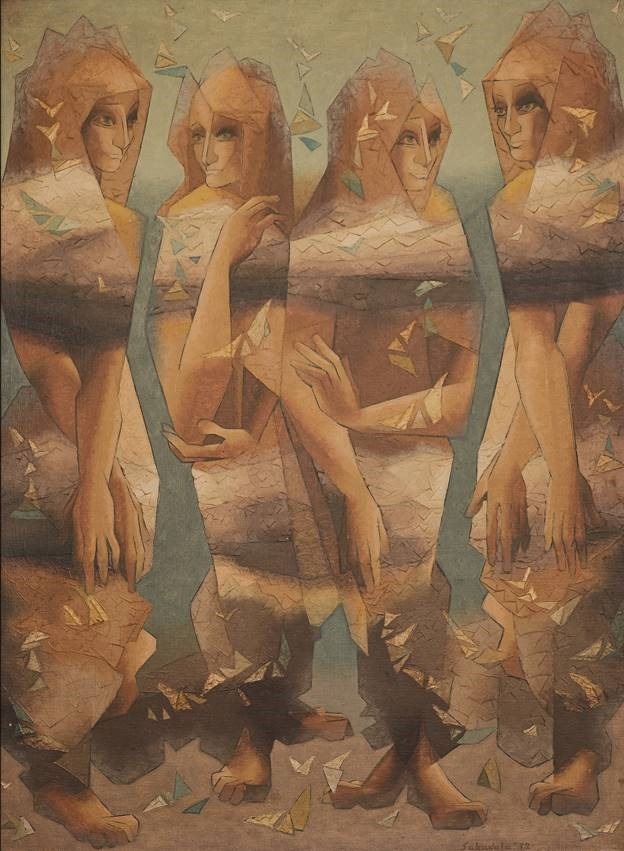

Elegy, Oil on canvas, 50 x 30 inches, 1967

Panoramic Opulence

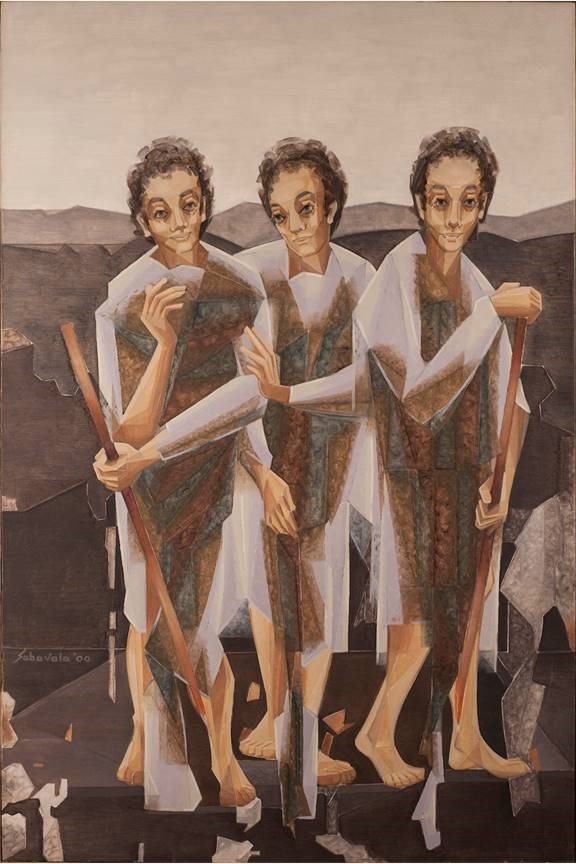

Sabavala explored human figures, too, a remnant from his academic style days. “He reached out to the experience of hard work and austere devotion, and memorialised, in his stylised manner, the shephard, the farmer, and the monk,” Hoskote says, adding, “He could also open his imagination up to enigmatic otherworldly presences such as apparitions, visitants, shamans, and wizards, inhabitants of the worlds of myth, legend, and archetype.” Even though these eclectic characters teem his canvas they are bereft of emotions and stand apart with their melancholic expressions albeit uplifted by Sabavala’s muted and sophisticated palette. Part of his art’s understated triumph lies in its academic formality and at the same time, his ability to transcend it to narrate an emotional state in simpler forms that any thoughtful viewer can profoundly resonate with. Mark Rothko famously encouraged a “consummated experience between a picture and onlooker.” The American abstract giant further declared, “Nothing should stand between my painting and viewer.” The same could be applied to Sabavala, who by resisting interpretation, urges viewers to stare at his paintings and drink from its mythic diffusions, much like a wayfarer who stands facing the sea, marvelling at its panoramic opulence. Shah agrees, “The more one sees his work and realises his dedication and integrity towards his practice, the more one grows deeply fond of him.”

The Accomplished Works

The artist’s highly personal spin on landscape can be best glimpsed in ‘The Shadowed Strand’ (1977) and ‘The Miasmic Shore’ (1967), both included in the exhibition. A quintessential Sabavala from the ’70s, ‘The Shadowed Strand’ depicts a luminous play of light, depth in the landscape, figures and tonality. All the attributes that make for a classic Sabavala. ‘The Miasmic Shore’ is another excellent example of the artist’s mid-career style. However, Shah cites ‘Sanchi’ (1960) as one of his landmark paintings, especially for representing a key shift in “Sabavala’s trajectory where he is transitioning from the structured cubist works to his own distinctive style of the landscape.” Hoskote calls it an “accomplished work”, noting, “the cubist framework of balancing tensions has been reshaped to serve the genius loci.” Yet, it is ‘Elegy’ (1967) that could well be the presiding genius of the show. It is Shah’s favourite work. “It has a very strong presence,” he says. “With its view against the light, a central path and two immense figures floating out of a pale mist, outlined by the bold diagonal cutting across the top half of the painting and the mountains worked on with palette knife and brush… this is Sabavala at his best.”

Fusing Different Schools

Sabavala’s art is strangely free of any style, be it Cubist or Impressionist though he followed both schools closely. Hoskote explains, “Between 1961 and 1964, Sabavala broke away from the suffocating formality of Synthetic Cubism, to which he had apprenticed himself at Andre Lhote’s academy in Paris. Departing from the impasto materiality of his earlier work, with its knife-edge lines, thick borders, and grand masses, he softened his paintings.” About his famed style, Sabavala had himself once said, “It’s an amalgam of academic, Impressionist and Cubist styles. Instead of being in just one discipline, I thought, ‘Can they combine and what would happen if I fuse them together’? This was the reckoning that eventually led to the Sabavala trademark. “He didn’t want to be confined to a particular style of painting,” Shah says, elaborating, “His artistic development offers an insight into the steady transformation of art as a medium of self-expression and discovery. You will find that he’s confident enough to keep revisiting themes and subjects from earlier paintings all the time.”

1/3

Santa Euphemia, watercolor on paper, 21 x 15 inches, 1954

Belongs To No Group

Born into an affluent Parsi family in Bombay (his father was a manager at the iconic Taj Mahal Palace Hotel), the aristocratic Sabavala lived a life of timeless beauty. In the 1940s, he travelled to Europe to study painting. Paris was his mother’s favourite city—and that’s exactly where her son spent some of the best years of his life. He brought back to India the technique and craft he had learnt in the epicentre of modern art. Back in India, the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group which included such titans as FN Souza, MF Husain and their associates like Tyeb Mehta, VS Gaitonde, Akbar Padamsee, Krishen Khanna and Ram Kumar were becoming a rising force, radically transforming our idea of what constitutes art and aesthetic. Evidently, history would recognise them as the founders of Indian modern art and they would go on to become some of India’s most popular artists. Thankfully, Sabavala has not missed that bus—though never a part of the PAG his contribution in the making of homegrown modern art is as heartfelt as it is enormous. As Shah says, “He welcomed the versatility of all influences.” After his return from Europe, Sabavala stayed in India, taking in all the inspiration that the diverse country had to proffer. Being a product of bourgeois may have meant easy access to high society and the cliquey world of art but for Sabavala, the early years were nearly as tough as for any struggling artist. One story goes that it was MF Husain who helped Sabavala mount his first exhibition at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, where the debut-making artist himself had to pin his works to the wall!

Jehangir Sabavala, Untitled, 60 x 40 inches, Oil on Canvas, 2000 (1)

‘India’ Missing in His Work?

Graceful, friendly and forthcoming, the cravat-sporting Sabavala’s perfect manners and calm demeanour has led to him being called a “gentlemanly artist.” Indeed, in his clipped English accent he loved to regale audiences and admirers with stories of the past as well as art in general. (He loved Juan Gris, whom he described as the “most monastic Cubist.”) Sometimes, due to his European temperament critics have dismissed him as “too romantic” and worse, “not Indian enough.” Was his work too removed from the Indian reality? Did India ever really exist in his work? He wasn’t a “social painter” as he was made out to be but “a much more serious artist,” Shah adds. Tellingly, his wife Shirin Sabavala, ever the champion of his art, pulled no punches when she said, in a TV interview with a media house, “What is truly Indian about Jehangir is his empathy for the Indian countryside and landscape. He’s never been able to paint a foreign landscape well. But when it comes to India, especially the Sahyadris or Deccan plateau his work catches the essence.” Hoskote recalls, “Over the 1950s and early 1960s, Sabavala embraced his homeland through travel, sketches, and an immersion in the cultures of India’s various regions. During these decades, the Sabavalas would travel to Kerala and Rajasthan, to Madhya Pradesh, the Sahyadri Hills and along the course of the Tungabhadra River.” Those walking into ‘Pilgrim Souls…’ can see for themselves a brief but important survey of that journey.