There is much that is debatable and untenable in the new book on Jinnah’s wife.

Who goes into history?

Who is worthy of a biography?

The shakers who change civilisation and our view of the world – the scientists, writers, painters and philosophers. And perhaps more than them, the movers, the captains and the kings and, if we believe Winston Churchill’s contention that behind every man who achieves anything there stands a woman, their consorts and their queens!

Article by Farrukh Dhondy | The WIRE

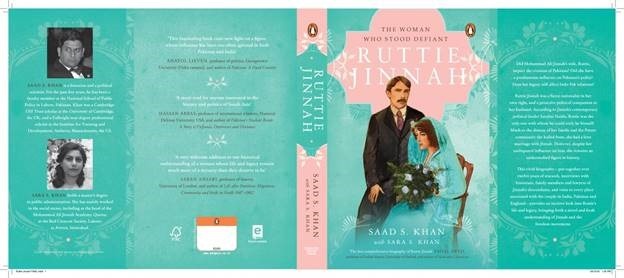

Nur Jahan for Jehangir, Josephine for Napoleon and now according to this multi-purpose, (let’s not call it ‘rambling’, yet) biography (Ruttie Jinnah: The Woman who Stood Defiant), Ruttie Jinnah for the man who was a participant in, if not wholly responsible for, the partition of India. A division which cost a few million lives and has resulted in one failed state and another discovering fundamentalist roots in its politics, prejudices and polity, which are the opposite of idealism and truly democratic progress.

Ruttie married the 40-year-old Jinnah after proposing to him, the book says, at the age of 18. She converted from the Parsi Zoroastrian faith into which she was born, to Islam in order to so do. She tragically died of an illness at the age of 29.

In various chapters and tiresomely repetitive passages, the ‘biography’ considers her allegiance to her new faith – its quality, it’s depth and its effect on her political stance. The writers seem to conclude that she was, with her husband, Muhammed Ali Jinnah, a devoted if not devout Muslim.

Nevertheless, her flirtation with theosophy, under the influence of her friends Annie Besant and Ranji Dwarkadas, a faith which she in the end rejected, seems to point to a wavering commitment to Islam. The book insists that Jinnah himself was a dedicated, if not ritualistic Muslim.

Also read: Rattanbai Petit and Mohammad Ali Jinnah: An Interfaith Marriage That Went Down in History

There are many books, quotes and much testimony to the contrary which are not included here in their insistence, bibliography or footnotes. For instance, there exists the persistent canard that he ate ham sandwiches and drank whisky. And there is the anecdote of Sir Abdullah Haroon who is reported to have said that he accompanied Jinnah to his first adult visit to public prayers at a mosque and told him to closely imitate all his ritual actions.

The authors don’t include or allude to any of these, perhaps apocryphal, recollections and instead quote someone called Ian Bryant Wells who writes that Jinnah was “strong in his religious beliefs”.

Born in 1901, Ruttie died of a wasting illness in 1929. She was married to Jinnah for 11 years. Her marriage and conversion caused great consternation in the family and the Parsi community. Her father Sir Dinshaw Petit disowned her and even launched an unsuccessful attempt in court to prove that Jinnah was after his money. The highest community body, the Parsi Panchayat excommunicated Ruthie and passed a resolution to exclude the entire Petit family from Zoroastrian rituals and ceremonies! There were similar reactions from sections of the Muslim community.

Saad S Khan and Sara S Khan, Ruttie Jinnah: The Woman who Stood Defiant, Penguin Random House, India (2020)

Most of the book is, inevitably, dedicated to Jinnah, his politicking, his trips abroad, his holidays and his indulgence of his young wife. Though the ‘biography’ is compelled to adopt as its central theme, the possible though speculative influence that Ruttie Jinnah, his companion to conferences may have had on his thinking, there can’t possibly be any proof that it was influence rather than just complacent agreement or cheerleading.

The problem with this thesis is that Ruttie died in 1929 and, though Muhammed Ali had achieved very many positions and triumphs till that date, his significant effect on history substantially begins when he returns from self-imposed exile in Britain to lead the Muslim League and then fight to the end for the creation of two nations – for the partition of India. It was not for nothing that a British negotiator called him “Mr Jinnah, the man with a problem for every solution.”

John Keats, one of the Romantics whom Ruttie must have read through her love for English poetry, died aged 25. Several biographies have been dedicated to his short life, each one a critical examination of the zeitgeist, the events and influences of his life and the verse. There seems to be a lot to say.

So, what is there to say about Ruttie Jinnah? Or put it another way, what do the authors of this ‘biography’ insist on saying, even in the passages not devoted to her husband’s subsequent or earlier life? Whatever little, by the author’s own admission, there is in letters she wrote and allusions in the autobiographies of others, is stretched to the limit.

Did Ruttie really affect or even participate in history? There is a detailed account of her heroic role in a demonstration to stop a memorial to Lord Willingdon. As her biographers argue that Ruttie influenced her husband into the two-nation demand, perhaps she also caused the statue-topplers of the Black Lives Matter movement through this act?

We have an account of Ruttie accompanying her husband in protesting against the deportation by the Raj of the editor of the Bombay Chronicle and staunch nationalist Benjamin Horniman.

A chapter is dedicated to her suffragette sympathies and publicly expressed opinions. She was also asked at the age of 21 to be the Vice President of the All India Trades Union Congress. She declined, but her biographers see no irony in this spoilt girl of Parsi aristocracy, who had never done a stroke of work in her life, being offered the position.

Spoilt? Yes. The biography provides chapters of evidence. Ruttie carried her retinue of pet dogs and cats on all her trips within India and abroad, which necessitated her taking a crew of servants with her on her sojourns to look after them. A chapter is dedicated to the stylish European clothes she wore and another to the encomiums she received from contemporaries for being beautiful, witty and having a charming laugh. The book does trace, interestingly, the reaction of the Parsis and sections of the Muslim community to Ruttie’s conversion to Islam and marriage to Jinnah.

The biography is eccentrically anti-Gandhi, characterising him, unfairly, as an opponent of the opponents to the erection of a memorial to Lord Willingdon, as a passive supporter of the Rowlatt Acts and even of being mealy-mouthed about the slaughter at Jalianwalla Bagh. This unresearched bias should by itself take the book off the historical biography shelves and relegate it to the Pakistani Missionary ones.

And then there are the blunders one should lay at the door of Penguin’s editors. The preface says: “…without caring to note that she converted to Islam, just like countless individuals, from Jesus to Jinnah’s own ancestors and those of most of Indian Muslims…” That Jesus converted to Islam will come as a total shock to the Pope and to keepers of chronology in heaven.

Then, placing London’s “Regent (sic) Park in Pall Mall” is not taking liberties with history, with which writers may tamper, but with geography, which is, kinda fixed?

The authors allege, “Charles Dickens once wrote, ‘Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them,’” accusing Dickens of plagiarism from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

Farrukh Dhondy is a novelist and script writer.