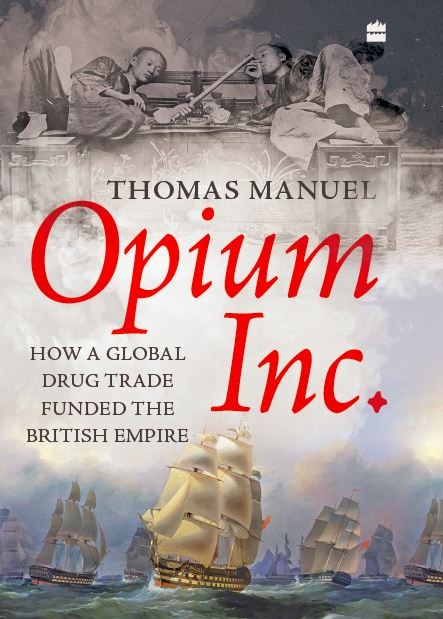

Thomas Manuel’s book ‘Opium Inc: How a Global Drug Trade Funded the British Empire’ shows how the Raj transformed entire farming economies in Bengal and Bihar into opium-producing machines.

Britain may claim it gifted civilisation to India but we know for sure that the Raj transformed entire farming economies in Bengal and Bihar into opium-producing machines over the 18th and 19th centuries. British agents smuggled tons of opium into China in exchange for tea, legally and illegally, taking silver in return. Millions were turned into addicts in China and India even as laws were passed against opium in Britain. Journalist-playwright Thomas Manuel asserts in his packed-with-facts book Opium Inc: How a Global Drug Trade Funded the British Empire that the British Raj in the 19th century was a narco-state – a country sustained by trade in an illegal drug.

Article by M. R. Narayan | The WIRE

Thomas Manuel

Opium Inc. – How a Global Drug Trade Funded the British Empire

HarperCollins India (August 2021)

At its peak, opium was the third-highest source of income for the British in India – after land and salt. Thousands of farmers cultivated and harvested the milk of the poppy – on their own or due to coercion, but always trapped in indebtedness. This made the British East India Company, which entered the hugely profitable trade in the 1700s, a drug cartel. After 1857, the Raj took over, raining more misery on India and China before global events halted opium trade in the last century.

Of course, opium was produced even during Mughal times. By 1688, Bihar’s annual output was over 4,000 chests. The East India Company accelerated poppy growth. Between 1830 and 1839, the area under cultivation doubled. By 1860, it doubled again. In three years, it doubled yet again. So, over a century, the lands devoted to opium cultivation went up by almost 800%. A Benaras Opium Agency and a Bihar Opium Agency came up to cater to the business in Uttar Pradesh and Bengal/Bihar respectively. Obscene profits were generated because of back-breaking exploitation of the peasants.

The opium was shipped to China. But there was a problem. The British were allowed to enter through just one port: Canton (now Guangzhou). The Chinese didn’t want to become another colony by letting the Europeans in to trade. Initially, in a bid to have more ports opened, the British shipped a huge quantity of gifts to the Qianlong emperor which needed 90 wagons, 40 barrows, 200 horses and 3,000 workers to ferry them to the Peking Palace. The emperor accepted the gifts but rejected the British request.

But the smugglers were so active that opium became a widespread addiction in China. When the Daoguang emperor discovered that his own son was smoking it, he ordered in 1838 a vicious crackdown that led to mass arrests, confiscation of 14 tonnes of opium and 43,000 opium pipes, besides a blockade of the European factories. The British capitulated, handing over 21,000 chests of opium which the Chinese burnt.

The British hit back – as viciously. After the First Opium War of 1842 that lasted two years, China was forced to open four new ports including Shanghai under the humiliating Treaty of Nanjing. It had to pay $21 million, partially as compensation for the cost of the war and partially for all the opium destroyed. The British seized Hong Kong too. A second opium war in which the French joined the British and invaded the Forbidden City led to a more permissive treaty, legalising trafficking in opium. Opium trade boomed. In 1865, one British trading house alone shipped opium worth 300,000 pounds – around Rs 250 crore today.

While poor Indians were squeezed to ensure bumper poppy harvest and production and sale of opium, many Indians made ‘super profits’ from the trade. Besides Calcutta, opium was shipped out of Bombay too, with the British collecting their fees and Indian merchants making a killing. One Indian who minted money thus was Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, whose wealth was estimated at Rs 40 crore when he retired from business. Many others from the Parsi and other communities were also involved in opium trade. Later, Jejeebhoy donated 245,000 pounds over time as he plunged into philanthropy and public life. He paid two-thirds of the entire cost of the Pune waterworks, created the JJ School of Arts and founded the JJ Hospital. The Parsis would endow more than 400 educational and medical institutions in the 19th and 20th centuries. Queen Victoria named Jejeebhoy the first baronet of Bombay.

Surprisingly, the nationalist movement in India remained silent on opium barring one notable exception: Dadabhai Naoroji. For the early Congress, nationalism meant fighting for better governance of India. Most leaders, while criticising liquor, felt the choice over opium was between national economic interests and the humanitarian costs. It was only in 1924 that the Congress passed its first resolution against opium. Similarly, while the history of missionary activity in China is inextricable from the colonial powers’ commercial activities, a section of the missionaries came out strongly against opium.

Eventually, both public opinion and diplomatic pressure from the US forced Britain to start distancing itself from opium trade. In 1913, a cargo of opium from India reached China, which received it and then set fire to it. But the British did not halt all opium business. In 1918, the Hong Kong government made a record $8.5 million from opium amid rising prices due to suppression in other countries.

India is one of the seven countries commercially allowed to produce opium for medical purposes under the 1953 Opium Protocol. But international bodies say that anywhere between 10-50% of legal production is diverted into illegal drug trafficking. Within India, around 2.1% use poppy products. A former narcotics commissioner of India feels that leaders from every political party are involved in the trade.

This book is a timely eye-opener on another dark side of British imperialism – “a story of immense pain for many and huge privileges for a few.”

M.R. Narayan Swamy is a veteran journalist.