Dinyar Patel’s biography of the politician shines a light on his multifaceted career, especially his campaign to be elected to the British parliament

Dadabhai Naoroji reached Bombay (now Mumbai) from London on the afternoon of 3 December 1893. An estimated half a million people thronged the streets to welcome him. Over a year ago, in July 1892, Naoroji had become the first Asian to be elected to the British parliament. He was in India to chair a session of the Indian National Congress in Lahore. It was to be the second of his three stints as Congress president.

Article by Niranjan Rajadhyaksha | Live Mint

Naoroji went on a whistle-stop tour of the country on his way to Lahore. His first halt was in Poona (Pune). At a public meeting there, the nationalist Bal Gangadhar Tilak described Naoroji as the great teacher of the new political religion of India, someone who transcended the old divisions. At the Congress session, Naoroji declared: “Whether I am a Hindu, a Muhammadan, a Parsi, a Christian, or of any other creed, I am above all an Indian. Our country is India, our nationality is Indian.”

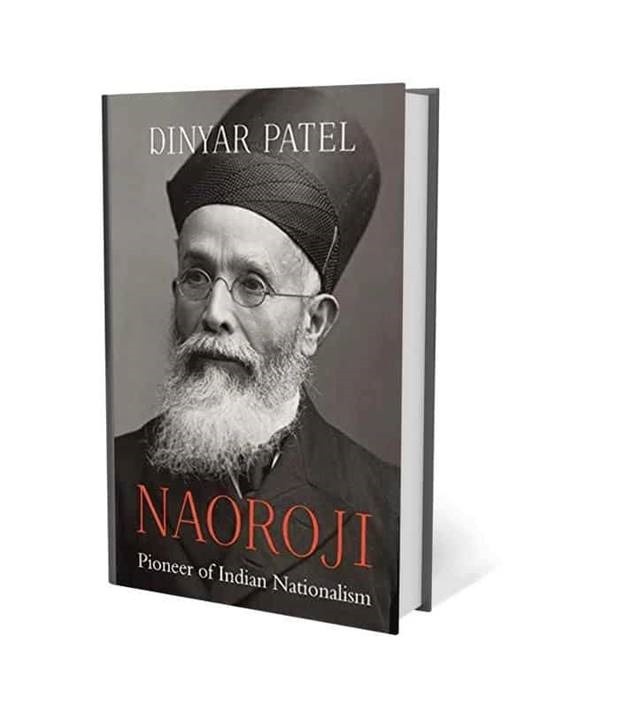

Naoroji—Pioneer Of Indian Nationalism: By Dinyar Patel, Harvard University Press, 368 pages, ₹699.

Historian Dinyar Patel has written a fine biography of the first Indian political leader of the modern era with a truly national following. He follows the many transitions in the life of his protagonist—from a young Parsi reformer in Bombay before the First War of Independence in 1857 to a relentless critic of colonial economic policy to his lonely fight for the Indian cause in the heart of imperial London to the radicalization of his final years. One photograph reproduced in the biography is of Naoroji at the Amsterdam Socialist Congress in 1904, in the company of Marxists such as Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Kautsky.

There was a tinge of disappointment later in his life as the Indian nationalist movement split into the moderate and extremist camps, leading to mayhem during the 1907 Congress session in Surat. Patel notes that the moderate camp found Naoroji to be too radical while radical leaders found him too moderate.

Some defining features of Naoroji shine through in the book. First, his commitment to factual arguments, as would be expected of a man whose first love was mathematics—it was a common attribute among the national leaders of his time before M.K. Gandhi introduced the politics of the inner voice. Second, the deep thought that went into constructing the famous argument of how British rule was draining India of its wealth, an argument that has subsequently lost some of its bite thanks to the work of contemporary economic historians who have painted a more nuanced picture of why India became an economic laggard. Third, his ability to build coalitions to further his political campaigns, be it with progressive businessmen in 1850s Bombay or with Indian princes after the 1870s or with Irish Home Rule activists during his parliamentary campaign. Fourth, his persistent interest in greater freedom for women, from setting up six schools for girls in Bombay in collaboration with Maharashtrian social reformers to the support he got from Emmeline Pankhurst and Florence Nightingale in his London campaigns.

Some of the best parts of the new Naoroji biography are the chapters on his campaigns to get elected to the British parliament. A comparison with the previous standard biography of Naoroji, written by R.P. Masani in 1939, is instructive. Only two of the 22 chapters in the old biography are on the parliamentary campaign. Nearly a third of the new biography by Patel focuses on the political work Naoroji did in London, which led to his winning the Central Finsbury seat in 1892.

Patel shows in evocative detail how Naoroji got support from Liberal Party grandees such as William Gladstone and Lord Ripon, his alliance with Irish Home Rule activists, his growing identification with working-class issues. The mastermind of his parliamentary win was Behramji Malabari, who arranged both political as well as financial support from India. One of the fascinating bits of information in the book is that since the British took control of Bombay through a royal charter rather than military conquest, Malabari argued that the citizens of Bombay had the same rights of parliamentary representation as British citizens. The royal charter of 1699 recognized the islands as part of the royal manor of East Greenwich. Also, Patel implicitly sets aside the urban legend that Muhammad Ali Jinnah managed the Naoroji campaign in Central Finsbury. There is no mention of him in the book.

Political biographies have gone out of fashion among academic scholars in recent decades. Patel has done well to write a deeply researched biography of a man who has been largely forgotten, other than for the textbook sobriquet of being the Grand Old Man of India. Many other interesting characters walk into the Naoroji story, from the Bombay polymath Balshastri Jambhekar to the cerebral Bengali civil servant R.C. Dutt. Their stories need to be retold as well.

But if there is one person who deserves a biography more than the others, it is the brilliant Parsi radical, Madame Bhikaji Cama, who got to know Naoroji well in London, was a guardian to his grand-daughter in Paris, was close to the revolutionaries at India House, and hoisted the first flag of independent India at the International Socialist Congress held in Stuttgart in 1907. Her biography is waiting to be written.

Niranjan Rajadhyaksha is a member of the academic board of the Meghnad Desai Academy of Economics.