Q&A with Hoshang Merchant | ‘Liberation does not come in a day’

The poet on his autobiography, sexuality, authorial identity and Section 377

By Amirta Roy | Livemint

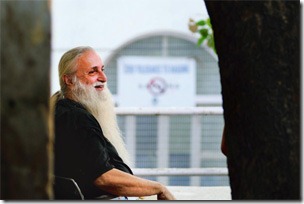

A Parsi who has studied Sufism in Iran and Buddhism in Dharamsala. A prolific poet whose staid day job happens to be that of an educationist. A Mumbai boy who has lived in Los Angeles and Jerusalem, and made a home in Hyderabad. One of the most prominent gay voices in the subcontinent, but one which does not believe in gay marriage. Identities merge in Hoshang Merchant’s latest book, the simultaneously witty and moving The Man Who Would be Queen, published 11 years after the critically acclaimed Yaarana, the first anthology of gay writing from India that Merchant edited. He spoke to Lounge about the new book and his concerns about gay identity. Edited excerpts from an interview:

Image Copyrights: Pradeep Gaur/Mint

The cover describes the book as ‘autobiographical fiction’. Is it more autobiography than fiction?

It is an autobiography. But it’s also fiction because memory plays tricks. Ghalib used to tell would-be poets, don’t talk about what you’ve eaten for breakfast. Different people eat different things. Say breakfast; everybody eats breakfast. Keep to the generalities, then people can relate. As it is, being gay is so strange for most people. People don’t talk about it. So you’ve got to tell them, “Look, there are thoroughly normal middle-class people who are gay”.

You’ve said you don’t like ‘gay’. You prefer ‘queer’. Yet you used ‘queen’ in the title.

I wanted to play on (Rudyard) Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King. So I said, “The man who would be woman”. But my students suggested “queen”. It’s slang, though I don’t know the exact nuance. A man who wears make-up? Like Quentin Crisp, the British foreign service officer who wore mascara to work during the height of the British empire. Later, when his (memoir) The Naked Civil Servant was published, the Queen Mother loved him and they became friends. My students call me the Quentin Crisp of India. But Crisp was 1930s, and I’m very now.

They are very literary. They don’t know where I’m coming from, or what I’m parodying.

While an author’s sexual identity is important to the understanding of his work, are tags like ‘gay literature’ limiting?

I didn’t write it as “gay” literature. I wrote as a human being who has a story to tell. My parents’ divorce was very traumatic. Gay people don’t divorce, only straight people do. There were no gay marriages at that time. So if gays follow straights into marrying, gay divorces will also follow. We read because we want experiences which are not ours. When I read a good lesbian book, I become a lesbian. When I read Nightwood by Djuna Barnes, I weep and weep for the two women in love. I forget my identity as a Parsi, or as a man. I can be a human for some time.

Also Read | The Man Who Would Be Queen | Speak, memory

So you don’t agree with the concept of gay marriage?

No, I don’t. Marriages are about property. Any marriage. Say somebody has served somebody for 25 years, and then he dies. So the other one inherits his property. But what about people who don’t have property? Or what about the kind of relationships that don’t last that long? The kind of relationships I’ve had—two months, three months, a few days. What does marriage mean to people like us? But I can understand that people have grown up in a heterosexual society and want to think, “Oh, I want to live with this person for ever”. I did too. I knew no better. I’d also grown up seeing my father and mother.

Do you think gay movements in India are still predominantly urban?

That’s not really true, though I’m out of it and only meet people when I attend meetings. But I’ve had readers from small towns tell me they enjoyed reading Yaarana or my poems. There was this man, from Hubli I think, who called to say that though he didn’t speak English he could identify with the simple language of the book. So to say it’s only urban or elitist is pure nonsense. But do you think I’d have been able to find my voice if I hadn’t had an English education, gone to the US and been with people like (feminist and author of erotica) Anaïs Nin?

And what is cosmo-politanism? It doesn’t mean anything. I lived in LA in the 1960s. I had teachers who were in the closet. I’d suspect they were gays. I’d fantasize. “Ill met by moon, proud Titania,” you know. But that never happened. We only knew for sure after their deaths. I couldn’t live in closets because I was a flaming queen with my swaying hips and long hair, but I’d have to go to brothels for sex.

Has the Delhi high court ruling on section 377 changed anything?

It will. Psychologically, it will. Like the emancipation Bill in the US. It stopped the lynchings, but oppression continued in other forms. Jim Crowism, toadyism. We’ve to go through the whole gamut. Liberation does not come in a day.