Aryanmehr, an Iranian blog has a long write up about the Persepolis celebrations of 1971.

We are awake

2,500-year celebrations revisited

By Cyrus Kadivar

The sky was dark on that Christmas Day in Paris. As I walked down the quiet Avenue du President Wilson the leaves lay sodden in the streets and the howling wind drove the rain against my face. Turning into the deserted Trocadero I rushed inside a smart café where I had agreed earlier to rendezvous with a former high-ranking official of the late Shah’s ancien regime.

Bustling through the door, my pockets stuffed with books and papers, I threaded my way through to a corner table, settled down, and ordered a glass of Beaujolais. The café was still a favourite haunt of exiles, journalists and ambassadors.

From my window I watched the lighting of the Eiffel tower. The waiter brought me my drink and I took out a notebook from the pocket of my drenched coat and started to review the list of questions I had prepared. I looked at my watch.

It was almost five in the afternoon and naturally I was becoming impatient for this meeting to take place as it had taken weeks to arrange. Soon I told myself I was going to meet a man who had played a key role in organising the lavish ceremonies staged at Persepolis in 1971 to commemorate 2,500 years of monarchy in Iran.

I had never met the gentleman before. We had spoken a few times over the phone and he had impressed me with his forthcoming views. He had sounded cordial and eager to talk and when he walked into the Café du Trocadero on that Tuesday afternoon, he greeted me warmly. But his gaze was overcast by melancholy as he removed his winter coat.

Had we crossed each other in the streets, Mr Abdolreza Ansari would have been, in the words of Garcia Marquez, one more incognito in the city of illustrious incognitos.

Even so, at the age of seventy-six, his elegance, like his dapper tailored blue suit and silk tie, was still notable. He had snow-white hair combed neatly, a pianist’s hands and expressive brown eyes. Only the weariness of his pale skin betrayed the signs of advanced age. The years of glory and power were long gone.

Abdolreza Ansari had been part of the Pahlavi elite. Born in 1925 he had been educated in the USA. He had degrees in economics and agriculture. He had started his career working as a Special Assistant to Bill Warne, the Country Director of Iran under Truman’s Point 4 technical assistance program. Under the Shah he had served in various posts: Governor of Khuzestan, Deputy Finance Minister, Treasurer, Minister of Labour. In 1968, after a disagreement with Prime Minister Hoveyda he had resigned as Minister of Interior to join Princess Ashraf’s inner circle where he assisted her in the numerous activities including the 68 charities and welfare organisations under her royal patronage. He was regarded as a capable and energetic technocrat with suave manners.

Before our meeting I had vowed not to gloat over the misfortune of those who had fallen into oblivion in the aftermath of the revolution that overthrew a dynasty and replaced the monarchy with a fundamentalist regime and theocratic republic. I wanted to be impartial and open to every witness and in this manner I hoped to set off along the path of history in search of truth, a path that had no beginning and no end. It has to be said that there were, and still are many people, including those who had served Mohammed Reza Shah, who blamed the organisers of these “jashnhaa”, or festivities, for the crash of 1979.

In these same Parisian cafes Iranian exiles still argued about unusual events, the terrible defeat of their dreams, sipping bitterness over what had gone wrong.

Admittedly, I was tired of the fervent debates about the whirlwind that had overturned the Shah’s world and laid waste to the achievements of millions of hard-working Iranians.

Thirty years after the spectacular events at Persepolis, I was not interested in passing judgment. I wanted the truth, or at least a glimpse of what had really happened behind the scenes.

We sat down near the window facing each other at the table. After exchanging polite preliminaries, Mr Ansari glanced at me with alert eyes and said, “What is it that you want to know?”

“Tell me about the party at Persepolis,” I said. “Who’s idea was it and what was your role in it all?”

Surrendering to a current of memories, Mr Ansari remained silent for a while as he contemplated my question. I knew that he had thought about the questions and the answers he wished to provide. But I also sensed a burden lifting.

“It’s a long story,” he sighed. “My memory is a bit rusty but I will try to give you a picture, as accurately and detailed as possible, even though it was so many years ago.”

And so Mr Ansari told me the story in a serene voice without letting his face reveal any emotion.

But as he spoke my mind floated to a time when the royal palaces were restored, gardens blossomed, and every ancient stone had regained its grandeur. Visions of my Persian boyhood kept getting in the way.

Ah Persepolis! As a child it had dazzled me with its brilliance and overwhelming symbolism. How could I forget the thrill of sitting on a double-headed griffon or placing my hand on the warm limestone surface, tracing the face of an Achaemenid warrior.

Countless images assailed me: lizards scurrying down the mass of fallen stones, the majestic columns towering above me, winged bulls with human heads, the sun baked royal stairway and diverse reliefs that spoke of reverence and absolute obedience to the sovereign ruler of the day.

I was remembering, I suppose, what I wanted to remember, going back in a sort of mental journey, starting again at the beginning of it all not bounded by time or space.

In trying to recover something of my childhood experience I realised that what had remained was a headful of brilliant moments, already distorted by the wisdoms of maturity.

It was time to bridge the gap by turning back the clock.

“The idea of holding a ceremony which would highlight Iran’s glorious past in the world was nothing new,” Mr Ansari said calmly waking me from my reverie.

In 1960, Shojaeddin Shafa, an Iranian scholar had sent a proposal to the Shah of Iran suggesting that he hold a colourful pageant thirty miles outside Shiraz in the ruins of Takht-e Jamshid, or Persepolis, the “City of Persians”, built by King Darius and burned to the ground by Alexander the Great in 331 B.C.

The Shah had given his tacit approval and a small committee headed by Amir Homayoun, a venerable senator, had been formed to consider a festival to mark the 2,500th anniversary of the original Persian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in the 6th century B.C.

“A small budget was allocated to the project,” Mr Ansari continued. “But for ten years nothing happened partly because the country was in the full throes of development and the government could not afford to allocate time or funds to such a celebration.”

In 1969 Michael Stewart, the British Foreign Secretary visited Iran and after meeting the Shah he was taken on a private tour of the famous ruins by Court Minister Alam, Prime Minister Hoveyda and Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Ali Khalatbari.

Later, during an evening reception thrown by Amir Khosrow Afshar, in his honour, the British Foreign Secretary, had described how much he had been deeply impressed by the fabulous Persepolis.

“Your Empire was founded by Cyrus. Xerxes extended it and Darius preserved it,” Michael Stewart told his hosts. “Your present ruler seems to me to possess something of the qualities of all three of these mighty kings.”

When Assadollah Alam had reported this to HIM, the Shah revived his interest in holding some sort of celebration and the Court Minister was asked to look into the details.

By the 1970’s there was a sense of self-confidence about both the Shah and his government.

Domestically, the White Revolution, was bearing fruit. Land reform, increased literacy, the enfranchisement of women, higher living standards and industrialisation was radically transforming the country. Internationally, the Shah had emerged as an essential Western ally with a major security role in the Middle East with one of the fastest growing armed forces in the Persian Gulf.

It is possible that given Mohammed Reza Shah’s mystical view of history, Persepolis had become a metaphor for his ambitions for his country: a phoenix rising from the flames, heralding a Great Civilization. It tied perfectly to his imperial dream: to make Iran within a generation the world’s fifth most powerful nation.

In early September 1970, thirteen months before the festivities, Mr Ansari, then aged 46, received a phone call. It was Princess Ashraf. She wanted to see him at once.

“Arriving at Saadabad Palace,” Mr Ansari continued, “I was taken to see HRH, Princess Ashraf. She greeted me in her reception room and informed me that HIM, her twin-brother, had finally decided to push ahead with organising an international gathering at Persepolis. Court Minister Alam had set up a High Council and I was to report to him without further delay.

The High Council responsible for the celebrations which reported directly to Empress Farah comprised of nine people: Court Minister Assadollah Alam; Hormoz Qarib (Chief of Protocol); Mehrdad Pahlbod (Minister of Culture); General Nematollah Nassiri (Head of Security and SAVAK); Amir Motaqi (Deputy Court Minister); Dr Mehdi Bushehri (Princess Ashraf’s husband and the Director of the Maison d’Iran in Paris); Reza Qotbi (Head of the National Iranian Radio and Television), Shojaeddin Shafa (Assistant Court Minister for Cultural Affairs), and Abdolreza Ansari.

“We would meet once a week at the Ministry of Court under Mr Alam’s chairmanship,” Mr Ansari recalled. “HM, Shahbanou Farah, took a direct interest in the details and the High Council would meet with her every two weeks at Niavaran Palace. I set up my headquarters in a rented office on Elizabeth Boulevard with a staff of twenty. The conference room was used to hold meetings and we often set up organisational and progress charts to keep track of what had to be done.”

That autumn, Court Minister Alam went to Paris where by chance he met Monsieur Pierre Delbee, the Honorary President of Jansen, an interior decoration firm in Paris’s fashionable Rue Saint-Sabin a few blocks from La Bastille. Alam spoke about the planned festivities and Delbee suggested that perhaps Jansen could help.

“When Mr Alam returned from his European trip he mentioned his meeting with Monsieur Delbee,” Mr Ansari recalled. “A few weeks later Monsieur Deshaies, the Managing Director of Jansen flew to Tehran to meet with the Shah.”

Monsieur Deshaies discussed the project with the Ministry of Court and suggested that a tent city inspired somewhat by Francois 1st’s sumptuous royal camp in Picardie erected in 1520 to entertain Henry VIII of England be modified and installed in the Iranian desert. A few months later Jansen presented a model of the proposed site which delighted the Shah and Shahbanou. A contract was signed and Jansen began preparations for the royal tents.

“At first we thought we would only invite 30 heads of state,” Mr Ansari said after swallowing a glass of mineral water. “But as our intentions leaked out to the foreign embassies we were flooded with requests and soon our list had grown by another 34 bringing the total number of world leaders expected to attend to 64. We also made provisions for the entourage of the leaders whom we expected would bring a maximum of five people with them. All these people would be housed in blue and yellow tents which were actually prefabricated apartments with a plastic cover thrown over them to protect them from the elements. Our team worked very hard as our country’s prestige was at stake.”

Invitations were sent to a galaxy of monarchs, queens, crown princes, presidents, sheikhs, sultans, vice presidents, a pride of prime ministers, ambassadors, legates, business figures and stars of the jet-stream too numerous to mention.

“From the start we realised that we were facing a colossal challenge,” Mr Ansari confessed. “There was so much to be done and so little time. So we divided the tasks between ourselves. For instance, Mr Shafa spent a month in Europe and America meeting with famous scholars who were invited to present papers at Pahlavi University in Shiraz. I was responsible for coordinating the activities between various organs dealing with the celebrations and providing necessary support and removing bottlenecks. I spent a lot of time on the phone, calling this person or that. I reported directly to Court Minister Alam. Mr Pahlbod busied himself with cultural programmes to be held in Iran while Mr Hormoz Qarib, a former ambassador travelled to England, Belgium, Holland, Scandinavia and France to discuss protocol details.”

In an interview with Habib Ladjevardi, the head of the Iranian Oral History Project at Harvard University, Sir Peter Ramsbotham (Britain’s ambassador to Iran) described a conversation he had at the time with Hormoz Qarib, a close and personal friend of his. In some ways it reveals the pressures that the organisers faced. “You know, the English, we acknowledge, are better than anybody in the world at protocol and arranging these things,” Hormoz Qarib told the British ambassador. “We are new to this, Western style; we could do it, of course, our own way, but we are having everybody here. We would like you to advise on this.”

During the weeks that followed every Iranian embassy in the world was instructed to hold cultural seminars and publish literature extolling Iran’s great past and contribution to human civilization. Moscow’s Hermitage, Paris’s Louvre and the British Museum in London were invited to promote the planned celebrations by sending a team of archaeologists and Iranologists to Shiraz.

“We were very happy when the British Museum agreed to lend us the original cylinder of Cyrus the Great,” Mr Ansari told me. “We later created a logo with a picture of this famous piece acting as a centre-piece and small copies were made in clay as special gifts for the guests. Mr Pahlbod, the Minister of Arts and Culture, invited several of Iran’s best artisans to workshops in Isfahan, famous for its wool. These people worked day and night to produce small, immaculate, silk carpets bearing the portraits of the important leaders who were to descend on Persepolis. It was a wonderful idea for it revived a practically extinct art.”

This was the easy part. The organisers were now faced with making a dream into reality. Given the remoteness of Persepolis which is located in the desert, there were many things to consider. Where would the guests stay? How would the security of so many heads of state be guaranteed? What kind of food should be given?

“You must understand that we Persians are hospitable people,” Mr Ansari said thoughtfully. “Our Ministry of Court was very capable of hosting small state dinners. But to do this in the middle of the desert with all those distinguished heads of state required an expertise that we did not have. We contacted the head of the Pahlavi Foundation’s hotel services and were told that they lacked the proper staff. Besides we had little experience in catering. So we turned to the French who are experts.”

Court Minister Alam and his deputy Mr Amir Motaqi contacted Maxim’s of Paris who agreed to help while Dr Mehdi Bushehri’s office at La Maison d’Iran on the Champs Elysees dealt with other essentials.

As it turned out it was this aspect of the celebrations, among other things, that was to gain press attention overshadowing the main reason for the celebration.

The French press gloated over the details. It was said at the time that Master Hotelier Max Blouet had come out of retirement to supervise a staff of 159 chefs, bakers, and waiters, all of whom were to be flown in from Paris ten days in advance of the banquet which was to be attended by five hundred guests.

When the menu, a closely guarded secret, was leaked to the press it almost caused a scandal. Headlines spoke of roast peacock stuffed with foie gras, crayfish mousse, roast lamb with truffles, quail eggs stuffed with Iranian caviar. For dessert the master chef suggested a glazed fig and raspberry special.

For almost six months the Imperial Iranian Air Force made repeated sorties between Shiraz and Paris flying goods which were then trucked carefully in army lorries to Persepolis. Each month supplies were driven down the desert highway to deliver building materials for the Jansen designed air-conditioned tents, Italian drapes and curtains, Baccarat crystal, Limoges china with the Pahlavi coat of arms, Porthault linens, an exclusive Robert Havilland cup-and-saucer service and 5,000 bottles of wine (including a 1945 Chateau Lafitte-Rothschild).

“Persian designers, not French ones as often claimed, came up with the idea of producing ancient uniforms of our illustrious ancestors,” Mr Ansari explained. “Military workshops in Tehran came up with various costumes and replicas of ancient trumpets were reconstructed to produce sounds not heard for 2500 years.”

The responsibility for the great parade at Persepolis was given to General Minbashian, the Commander of the Imperial Army, whilst his brother, Mr Pahlbod, the Minister of Arts and Culture, oversaw the details. Hundreds of Iran’s finest horses, camels and 1,724 soldiers were mobilised for the great parade day. Costumes, fake beards and wigs, flamboyant uniforms, chariots, weapons, and regalia were made after detailed research by teams of military historians. There was even a replica of three ancient ships dating back to the glorious days of Xerxes for the occasion.

Meanwhile, Carita and Alexandre, two of Paris’s top hairdressers were invited to provide a service to the foreign guests and their ladies.

At one point the Ministry of Court realised that the Shah’s adjudants needed smart new uniforms. “There was an old court tailor by the name of Zardooz,” Mr Ansari recalled nostalgically. “He had an atelier in Sepah Avenue near the Army HQ building in Tehran. I had my ceremonial uniform usually worn during the royal audiences sewn by him. When we asked him to prepare thirty new uniforms for the celebrations, Mr Zardooz complained that he did not have the people or necessary tools so Mr Alam turned to Lanvin and asked them to duplicate the extra uniforms.”

An Iranian publisher arranged to take stills of a 700 year old Shahnameh under the supervision of Mrs Attabai and 2000 copies were superbly reproduced and later became a collectors item. William MacQuitty, a famous photographer came to Iran and snapped photos for a marvellous book called: Persia: The Immortal Kingdom. It was produced by Ramesh Sanghvi, the Bombay born author of a biography on HIM. This rare book was translated into a dozen languages and many experts like Ghirshman and Minorsky wrote the text.

“MacQuitty and I became good friends,” Mr Ansari recalled fondly. “He was an extraordinary man who had been the producer of A Night To Remember, the 1958 film about the sinking of the Titanic. He was a rather tall man and had salt and pepper hair and was in his sixties when we met. He was absolutely fascinated by Iran.”

Shahrokh Gholestan, a prominent filmaker, was commissioned to gather a crew to make a film of the events. Hollywood director actor, Orson Welles came to Iran to discuss the project. It was called, “Sholehayeh Pars”, or, “Flames of Persia”.

Mr Ansari stressed to me that many people outside the High Council for the festivities provided crucial services. For instance, Amir Aslan Afshar, Iran’s ambassador in Washington D.C., hosted interesting seminars on Persian history and modern Iran. Mr Parviz Khonsari, Assistant Foreign Minister, dealt directly with the various diplomatic missions hosting numerous receptions at Tehran’s brand new Hilton Hotel. General Khademi, the Director of Iran Air, took control of the skies, and Mr Mansour Rouhani, the Minister of Water & Power, took charge of the electrification of the vast area in and around Persepolis, Naqsh-e Rostam and Pasargad.

We stopped talking and ordered a coffee. Once again I found myself remembering a trip with my parents and my brother Darius sometime before the ceremonies.

Mr Ansari listened to me politely as I described how General Boghrat Jaffarian, a marvellous officer later killed during the revolution, had given us a tour of the encampment.

Driving us around in an army jeep, Jaffarian seemed proud of his men. He pointed at the soldiers, most of them naked to the waist and sporting long beards under the boiling sun.

These were the men, he said, who would later march in the greatest parade of history representing the armies of the successive dynasties that had ruled Iran. Later General Jaffarian dressed in olive green fatigues had given us a preview of the royal blue tents and the private chambers of the king and queen.

Each tent was decorated differently in classical and modern style. The walls of the banqueting rooms were made of velvet sewn in France covered by a gigantic blue-pink canopy made I later found out of synthetic plastic of reliable and durable quality.

“How many tents were there?” I asked.

“There were two enormous tents, one being a reception area and the other a banqueting hall,” Mr Ansari explained.” He pulled out a fine looking pen and began to draw a number of circles on a white napkin. “The largest of these tents was the Tent of Honour about thirty-four meters in diameter,” he said. “The Banqueting Hall was 68 by 24 meters in length and width. There were 50 smaller tents painted in yellow and blue which branched out in five avenues in a star-shaped pattern. There was also an enormous fountain which was flood-lit at night.”

While the workers sweated to complete the camp at Persepolis, the Hessarak Institute had to launch a campaign against thousands of poisonous snakes that populated the desert and whose sting could have killed the distinguished guests. An area of 30 kilometers was cleared and disinfected.

“I will never forget the sight of all those jars of exotic creatures, snakes, scorpions, and lizards,” Mr Ansari recalled creepily. “On one of my inspection trips there a team of zoologists had collected hundreds of unknown species in special jars kept in a big van. In some ways we had unwittingly helped research.”

In addition to collecting crawling creatures the Agricultural department planted acres of small pine trees along the newly asphalted road leading to the stone ruins. In order to light up the dark, 30 miles road from Shiraz to Persepolis, the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) set up torches fuelled by oil barrels set 100 meters apart from each other. Hundreds of thousands of commemorative posters, stamps and coins were made to mark the auspicious occasion.

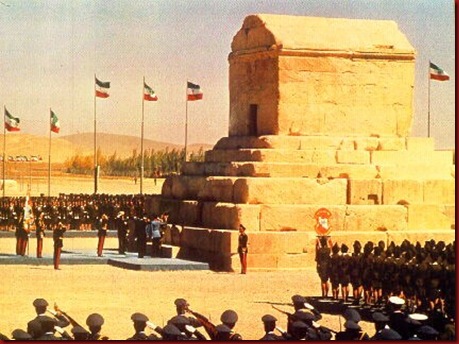

Teams of bulldozers demolished a few old village houses in the area known as Pasargad where the opening ceremony would later be held in the shadow of Cyrus’s empty tomb. And the town of Shiraz famous for her poets and beautiful gardens was cleaned and the façades of shops and houses repainted.

The Ministry of Tourism ordered the construction in Shiraz and Persepolis of two brand new hotels, named Koroush and Daryoush, each with a 150-room capacity.

The dormitories at Pahlavi University were repainted and the cafeteria refurbished to accommodate the various scholars and journalists. In April 1971 a delegation headed by the Court Minister arrived in Shiraz to inspect the project work at Persepolis.

“When we arrived in Shiraz,” Mr Ansari recounted, “we were met with great pomp and circumstance by Mr Sadri, the Governor of Fars, and General Zargham. We travelled in a government car with a heavy escort to see the works so far.”

The delegation met with workers who expressed great pride in their achievements, as they were keen to demonstrate to the visiting foreigners the best face of Iran. In his slightly old-fashioned, feudal way, Alam who had a feel for the common man had thanked them all warmly for their patriotic efforts before moving swiftly to inspect the building works at the nearby Daryoush Hotel.

“When we got there,” Mr Ansari said laughing, “Mr Alam’s face went completely white. Instead of a modern hotel the only thing visible was a metal structure stuck in the ground.”

The Court Minister could not believe his eyes. Six months left to the big event and no hotel.

“Mr Alam was fuming all the way to the Governor’s Palace in Shiraz,” Mr Ansari remembered. “Once the delegation members had settled down in their seats, Mr Alam exploded. He shouted that the Persepolis events was of national importance. Pointing his finger like a pistol at the faces around the table he warned them that if they failed in their duties he would personally shoot everyone present in the room before killing himself. I believe he meant every word of it.”

Throughout the hot summer months the feverish pace of work continued unabated. Every day in Tehran, millions of residents in the capital drove past the monumental white Shahyad tower as the finishing touches were completed under the supervision of Mohsen Foroughi, one of Iran’s most revered architect.

Almost every other city, town and village in Iran underwent a face lift and newspapers reported how four hectares of earth was being delivered to the Tent City in Persepolis so that George Truffaut, the Versailles florist, could create a perfumed garden with a variety of roses and tall cypresses.

By early October a dark cloud had descended over the celebrations. The liberal press was very critical. anti-Shah activists began to spread rumours that the “dictator” Shah was planning to hold a fabulous party at the expense of the “starving Iranian people”. In Pahlavi University several students were caught by the secret police for writing slogans in the campus toilets denouncing the planned festivities. The most scathing attack came from the exiled Khomeini who from his Iraqi base in Najaf condemned the “evil celebrations”.

“I say these things because an even darker future, God forbid, lies ahead of you,” the Ayatollah warned the Shah.

There were a number of security problems, just beforehand, because Iraq,had been training assassins in Iraqi territory to start a wave of terror disrupting things, so that they could demonstrate that the Shah could not keep security in his own realm. And therefore a lot of people would cancel their trip or would spoil the whole atmosphere.

“SAVAK was particularly active during that time,” Mr Ansari conceded. “There were many serious acts of terrorism during this time. The US ambassador was almost kidnapped one night in Tehran. Then there was the Siahkal incident in Ghilan. Terrorists attacked a number of banks, assassinated police officials and blew up cinemas. Security became tough especially after the Mujaheddin and Fedayeen guerrillas threatened to drown the Persepolis events in a bath of blood.”

“How many were arrested?” I asked.

“I once asked General Nassiri the same question,”Mr Ansari said. “This was after the ceremonies were over. He smiled and said that in addition to the extraordinary security measures he had instructed SAVAK to detain 1,500 suspects.”

“What happened to them later,” I asked, having read that they had disappeared.

“Nassiri, who was later executed after the revolution told me that they were released after a few days,” Mr Ansari said. “Let’s face it. We were not as sophisticated as the West. Sometimes the methods were crude and some innocent people may have been arrested. But imagine if a terrorist had succeeded in getting through.”

The Shah’s enemies did not succeed in boycotting the celebrations but a few important guests had a change of heart, among them the Queen of England, President Pompidou of France (he sent his suave prime minister Jean Chaban Delmas) and Richard Nixon (represented by US Vice-President Spiro Agnew).

According to recently emerged documents released in October 2001 to the Public Records Office in London, Queen Elizabeth was urged by the Foreign Office not to go as they feared the celebrations were likely to be “undignified and insecure”.

Prince Charles turned down the opportunity to stand in for his mother because the trip would clash with his naval training commitments. This threatened to cause a diplomatic rift between Iran and Britain as diplomats warned the Shah would take this as a personal rebuff, “with possible unfortunate consequences” they warned. At the end, the Duke of Edinburgh and Princess Anne eventually volunteered to attend and by all accounts they had a very good time.

Mohammed Reza Shah was a proud man and although he may have felt snubbed by some of the key defections he did not show it. As he told the French prime minister later, “The great desert wind and the blue sky of Persepolis have banished the alleged dark clouds between our country and that of France.”

At last, by the time the last roses of Truffault had been laid and the fountains switched on, the Shah had a list of important VIP’s who had accepted to come to Iran which included: Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, King Hussein of Jordan, Prince Juan Carlos of Spain, the King and Queen of Belgium, the Kings and Queens of Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Holland, President Tito of Yugoslavia, President Padgorny of the Soviet Union, Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco, President von Hassel, president of the German Bundestag, the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg, Abdul Rahman of Malaysia, Cardinal de Furstenberg, the Pope’s special envoy, ex-King Constantine of Greece, President Ceaucescu of Romania and his wife, President Svoboda of Czechoslovakia, the President of Lebanon, and President Marcos and his wife Imelda.

The show that everyone had waited for could now begin.

Over 69 heads of state or their direct representatives converged on the fairy tale city of Shiraz. In a patchwork of colour, in a whirl of salutes, bows and curtsies, familiar faces in the global arena stepped out of their shiny aircrafts over red carpets fringed with immaculate guards of honour into the welcoming Persian sunlight. The flags of the guest nations flew in salute as the VIP’s flew in.

“We had established a Control Room in the Darius Hotel,” Mr Ansari said, filling my head with more details. “Here the team had everything worked out, closely monitoring events, ticking off names and checking organisational charts. The phones never stopped ringing. Too much was happening. For all the arrivals protocol had to be kept and observed. The late Mr Hormoz Qarib, a small and intense man, who passed away last year in Lausanne, almost had a nervous breakdown.”

Mr Hormoz Qarib, the Chief of Protocol had been driven almost insane by the changes demanded by the guests who often wanted to ensure that they could sit where they wanted and not always going by the rules. It was a delicate task which Qarib and his staff were able to overcome by delicate diplomacy and good-humour.

“What really broke Mr Qarib,” Mr Ansari remembered, “was the total number of guests expected for the state banquet during the three-day festivities in Persepolis. Many of the guests had brought extra people in their entourage and he feared that we would run out of places. The poor man came into the Control Room dressed in his beautiful court uniform with his medals and slumped into a chair, exhausted. Then he began to weep, tears rolling down his cheek.”

After the Chief of Protocol had been comforted by his understanding colleagues it was decided that if worse came to worst, the Iranian guests (primarily those involved in organising the celebrations) would give up their seats.

“At the end our fears were unfounded and we managed to fit everyone,” Mr Ansari remembered.

In the words of Orson Welles, “This was no party of the year, it was the celebration of 25 centuries!”

Throughout the days and nights, escorted cars and coaches drove through Shiraz into the desert towards the great ruins of the kings of antiquity; the historic birthplace of the Persian empire. The guests arrived to find a camp shaped like a star branching out the Royal Pavillion representing the five continents. Each head of state had an apartment with a sitting room, two bedrooms, and two bathrooms, and a service room with an electric stove and ironing board for their entourage. The new buildings were a major piece of construction. One day, the Iranian organisers hoped it would become a super hotel. In each room the distinguished guests found carpet portraits of themselves woven by Iranian artisans from the finest silk which hung in their sitting room.

“Persia was in gala mood,” said Orson Welles, the narrator of “Flames of Persia”, the movie made of the Persepolis celebrations. “In Shiraz,” he said lyrically, “where there is a garden known as the Bagh-e Eram (Garden of Paradise) the lights twinkled like diamonds and bubbles in a glass of champagne.”

The Shah and Empress Farah were in constant attendance on the newly arriving guests, their hands stretching a hundred times in welcome. The various leaders who came to Persepolis had a unique opportunity for relaxed conversation, visiting each other in their respective tents. Prince Philip piloted his own plane down. And he raced Prince Bernhard down, because they were great friends. And then, when they were there, they hobnobbed, visiting different tents. His great friend was the King of Jordan. They were all about the same age. King Constantine of Greece and Baudouin of Belgium. And they had fun. They would go to each others’ tents and have drinks in the evening. They loved it. It was all a great success. And Princess Anne enjoyed herself too.

At Pahlavi University an international congress of 250 scholars were already in session in Shiraz hosted by the Chancellor Farhang Mehr, a prominent Zoroastrian.

“The papers they read on Persia,” Mr Ansari noted, “were to be read and circulated to academic institutions throughout the world. This was a great achievement.”

The Celebrations began with a simple and moving ceremony at the tomb of Cyrus the Great at Pasargad shortly before noon on October 12th, 1971, 2,510 years after the Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 B.C. Accompanied by the Empress Farah and Crown Prince Reza, the Shah, dressed in his emperor’s uniform, delivered an emotion-packed eulogy to his illustrious predecessor and vowed that Iranians today would continue to prove worthy heirs of their glorious past. In his prayers to the founder of the Persian empire, the Shah said these unforgettable words which were beamed live on television worldwide:

“O Cyrus [Koroush], great King, King of Kings, Achaemenian King, King of the land of Iran. I, the Shahanshah of Iran, offer thee salutations from myself and from my nation. Rest in peace, for we are awake, and we will always stay awake.”

Mr Ansari who witnessed the event had, like his monarch, been visibly moved by the solemn occasion but he could not recall the moment, shortly after the Shah had finished his speech, when a desert wind had swept over the onlookers.

Later that night, the Shah and the Empress Farah received their guests in the red damask reception room of the state banqueting tent which dominated the canvas tent city. The roll call of majestic sounding titles, the aides de camp hovering in attendance, the chandeliers hanging high above the tables, the music played from a minstrel’s gallery, the gold plated cutlery used by the heads of state all seemed to hark back to a European court of a century or more ago.

The Shah with the Queen of Denmark beside him, then led the procession into the banqueting hall which was draped in pink and blue. He was followed by the Empress and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. The principal guests were ranged on one side of a long zig-zag table designed to accommodate the maximum number of people as well as blur questions of protocol. The other guests, who included ambassadors and members of the suites of heads of state, sat in groups of 12 at smaller tables. All in all over 600 guests feasted on a menu never to be repeated nor forgotten. The peacocks were mainly for decoration, as the peacock was an emblem associated with the Persian crown. Journalists were quick to pick up the fact that the Shah did not like caviar and ordered artichoke hearts instead. It was indeed a night to remember.

The next day, on October 13th, a magnificent parade was staged at Persepolis.

“The setting sun gilded the columns of the palace of Persepolis,” wrote Fereydoun Hoveyda, the Shah’s UN ambassador and brother of the ill-fated prime minister, Amir Abbas. “Guards dressed as Achaemenid warriors with their curled hair and beards were lining the great double stairway, their lances flashing.”

A company of horsemen who had set out from Tehran the previous day, rode up to the dais where the royal family and their guests were seated. A captain dressed like an Achaemenid dismounted to present the Shah a handwritten parchment.

Looking splendid in his ornate Commander-in-Chief uniform the Shah read another message extolling the great kings and noble Iranian people, his flat voice projected over the waiting crowd of kings, presidents and prime ministers by an elaborate loudspeaker system. “On this historic day when the whole country renews its allegiance to its glorious past, I, Shahanshah of Iran, call history to witness…”

The trumpets were sounded. “Persia was on Parade,” said Orson Welles in a grave voice.

Like millions of Iranians I watched all this on our black and white television, fascinated but sad not to have been there in person. Golden chariots, warships, fierce warriors marched in the setting sun. Every dynasty was represented: Achaemenids, Parthians, Sassanians, Safavids, Afsharids, Qajars, Pahlavis. After watching this parade my brother and I donned paper crowns and fake beards made of cotton. Then to the delight of our parents and little sister Sylvie we marched up and down the garden pretending to be the very kings whose names we bore.

Mr Ansari recalled that several days before the parade a shipment of umbrellas had been ordered to shade the guests. “To my horror they were not black but in dozens of colours. At the end this mistake turned out to be a great photo opportunity when the distinguished guests opened them creating a rainbow effect.”

“After sundown,” Mr Ansari continued, “the guests followed their hosts into the starlit Persian night for a marvellous Son et Lumiere performance among the great stones where it all happened. Given the chill in the air I had taken the precaution to supply the guests with electric blankets. I still remember watching the Emperor of Ethiopia who was sitting next to Her Majesty, the Shahbanou. He was a very old man and grateful to be wrapped tightly in a blanket.”

From the tomb in the mountainside overlooking the ruined palaces where he ruled 500 years before Christ, the voice of Darius the Great spoke in the dark, but in French. Andre Castelot, France’s eminent historian, recounted the glories of Xerxes and the last days of the Persian empire. The columns of Persepolis were bathed in white light then gradually they turned red and the sound of fire mixed with the drunken orgy of Greek soldiers. It was the sacking of Persepolis by Alexander all over again. The guests were thrilled and applauded.

Until now everything had gone well. The Son et Lumiere lasted for about thirty minutes. It had been planned that after this the lights would come on and a few minutes later the night sky would have been lit up by a stunning fireworks display.

“But even the best of plans can go wrong,” Mr Ansari said. “When the Son et Lumiere show ended the lights went out and we were plunged into darkness for about 3-4 minutes. Then suddenly, an explosion. A fantastic display of fireworks lit the sky sending shivers down a few people who thought it was a terrorist attack. Well, this went on for a few minutes and still the lights did not come on.”

“At this point everybody became worried,” Mr Ansari recalled, “I ran quickly to the control room while the fireworks exploded above me. The man responsible for the lights was an ordinary worker. He was standing outside his room so overwhelmed by the show that he had forgotten to switch back on the lights. Well, I got that fixed.”

The lights came back and everyone gave a sigh of relief. The Shahbanou turned to Alam and whispered angrily, “Who’s silly idea was it to have fireworks?”

The Court Minister bowed politely and in a calm voice addressed Empress Farah. “Your Majesty,” he said in his candid style, “it was my idea and I think it was a rather nice display’.”

The Shah, on the other hand was amused. He had enjoyed himself. He stood up, proud as a peacock, and walked back to the tents. “It was an emotional moment to see the high and mighty following behind HIM,” Mr Ansari said. “During the Conference of Tehran, in 1943, the representatives of Russia, Britain and America had paid scant attention to HIM who had to swallow many insults to his pride. Now in 1971 it was the other way around. The world was paying respect to his achievements and position as a world class leader. I recall how some of the other international delegates had fought with our chief of protocol to get a room in a tent instead of lodging at a hotel.”

That night, after the parade, the fountains that inspired the poets of Persia whispered their watery music.

As the flags drifted in the evening breeze after the formalities of the state reception, the Shah donned his dinner jacket, and the Empress a white gown, inviting their guests to a Persian party. The dinner that night was really a Persian buffet with mountains of saffron rice, Fesenjan (pommegranate stew) chicken and lamb kebabs.

In the film made by Shahrokh Gholestan one cannot help notice how relaxed and intimate everyone looked that night. Given the horrors that descended on Iran eight years later, the film captures a night that in retrospect seems straight out of the 1001 Nights. Before meeting Mr Ansari I had studied “Flames of Persia” and memorised several scenes among them the Shirazi dancing girls, swaying like trees in the wind, their turquoise costumes shimmering under the crystal chandeliers. One telling scene showed HRH Princess Grace in a flowing dress, smiling at a fellow guest. Another one caught Prime Minister Hoveyda leading the wife of the French Prime Minister by the arm just as the Shah of Iran sits down at his elegantly laid out table joined by the Soviet and Turkish presidents in a cacophony of traditional music.

The following morning, many of the VIP’s left Persepolis and those who stayed were crowded in coaches and driven to the airport in Shiraz and flown to Tehran.

The Celebrations ended with a few more programmes in the Iranian capital including a visit to the Mausoleum of Reza Shah, the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, by the Shah and the Emperor of Ethiopia (overthrown and murdered a few years later by army rebels) who laid a wreath. Then there was a spectacular inauguration of Shahyad tower in honour of the King. The Mayor of Tehran, Gholam Reza Nickpay handed the Shah a replica of the Cyrus Cylinder.

“Persepolis put Iran on the map,” Mr Ansari told me. “The American charge d’affaires kept telling me that it was the best exercise in public relations he had ever seen. Had we done it any other way it would have cost us many more millions.”

The Shah was very pleased by the whole thing. His country’s honour had been well served. He ordered his Court Minister to reward all those who had made the impossible possible. Medals were awarded and key individuals promoted. Others, like Mr Ansari, received an autographed photo of HIM and returned to their old jobs. Mr Ansari’s office was handed over to Dr Mohammed Baheri, a former Justice Minister and the assistant court minister for Social Affairs.

“How did you feel when it was all over?” I asked.

Mr Ansari finished his espresso. “Frankly,” he said, “I was so tired and exhausted that I crept into my bed and slept for two whole days. It had been quite nerve-wracking. Like my colleagues I had worked sixteen hours a day for thirteen straight months. Throughout this period I had lived and breathed nothing but Persepolis. I dreamt about it and had my shares of nightmares worrying that it would all go wrong. Fortunately, the whole event was something that made us all proud.”

But the Iranian people’s reaction was mixed. Some loved it while others, wondered privately if the money could have been spent in a better way. Cynics called it a “ridiculous farce” and pointed to the absence of the Iranian public at the actual ceremonies as a sign of imperial arrogance. The Shah’s enemies, especially the Confederation of Iranian Students, made great capital out of the event. The Iranian consulate was bombed in San Francisco. A few foreign journalists who had been wined and dined in Shiraz slipped out of their hotels to film the poor villages in the outskirts and used it in their documentaries to show a contrast between the dazzling elegance of Persepolis and the misery of the poor. Khomeini called it the “Devil’s Festival”.

Shortly after the ceremonies had ended almost every major newspaper in Europe and America began to criticise the lavish display which only a few days before had been praised as the “greatest gathering of the century”. Speculating on the cost, Time, a magazine usually sympathetic to the Shah, put the figure at a shocking $100million while the French press doubled the numbers. Under heavy criticism for the expenditures, Minister of Court Alam called a press conference on October 24th and announced the celebration expenses at $16.8million.

The Shah finding himself somewhat on the defensive described critics who alleged the celebration had cost $2billion as “not sound of mind”. In any case, he told one journalist, Iran “couldn’t care less”. As far as he was concerned the whole thing had been a success. Besides what were people complaining about? Did they expect the Imperial Court of Iran to offer their guests “bread and radishes”?

Strangely enough, thirty years after the event, the British press resurrected a story about how the Foreign Office had advised the Queen who wanted to go not to attend the Shah’s party and referred to the Persepolis event as “one of the worst excesses of the Pahlavi regime”. Once again they alleged that the ceremonies had cost $50-$500million. Where did these figures come from, I wondered?

“So how much did it cost, Mr Ansari?” I asked, praying that he would not feel insulted.

Once again the fine looking pen came out as Mr Ansari totted up the numbers in Persian.

“One hundred and sixty million tomans,” he said. “That’s about $22 million dollars in those days.

“Is that all? I gasped. “So what about all these astronomic figures we read in the press?

“Not true,” he said. “One third of the money was raised by Iranian industrialists to pay for all the festivities. Another third was from the budget of the Ministry of Court and went to pay for the Tent City. The rest of the money came from the original budget under Senator Amir Homayoun which he had invested in 1960 and was spent on the building of the Shahyad tower. The remaining funds amounting to $1.6 million was, by order of HIM, allocated towards the ongoing construction of a mosque in Qom which on completion was to be named after the late Ayatollah Boroujerdi, the most prominent Shi’a leader in the world.”

When I asked Mr Ansari what had been his proudest moment in the celebrations his answer was unexpected. “Before the Persepolis event,” he said, “I had suggested to the High Council that we should build 2,500 schools in the poorest rural areas. People were invited to sponsor a school for $4,000 which would bear their name. HIM liked and approved the idea and I later submitted a lengthy proposal to the Education Minister, Mrs Farrokhro Parsa, who agreed to supply the teachers drawn from the Literacy Corps. On the first day of the events 3,200 schools had been opened and when the bells were rung 110,000 children went to their classrooms. That I believe was my biggest joy.”

“Sadly,” I said, “the foreign media seemed to have been more interested in Haile Selassie’s little dog Chu Chu and her diamond collar than what you just mentioned.”

“True,” Mr Ansari replied. Then he added, “Did you know the French government spent $200 million dollars on the 200th anniversary of the fall of the Bastille? And what about the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on the late Ayatollah Khomeini’s tomb?”

Since the revolution an estimated forty percent of the Iranian population live under the poverty line and yet the hardliners in the ruling Islamic regime continue to spend millions on sponsoring terrorism and anti-American street demonstrations.

Even in the West many projects have cost more than Persepolis ever did. In the summer of 2002 the Queen’s Golden Jubilee will be held across Britain to promote monarchy and thank Her Majesty’s subjects for half-a-century of loyalty and service. That night, while talking to Mr Ansari, I wondered about the millions that will be spent. I cited the costly Millennium Dome project and the £53m fund raising campaign for renovating the fifty-year old Royal Festival Hall in London. And this was being done in a city with hundreds of unemployed and homeless persons sleeping rough on the bridges and street corners.

Was the West guilty of hypocrisy?

It is a forgotten fact that the celebrations at Persepolis was only a component of a greater programme of development in Iran. It was the cherry on top of the cake.

In the 1950s Iran was considered an underdeveloped country. In the 1960s it was promoted to a developing nation and by the 1970s it was seen by many who came to Persepolis as a country with a rich history and on the road of becoming a developed nation.

For the Shah the events in Persepolis allowed him to show the world his country’s new importance.

Mr Abdol Majid Majidi who was responsible for the 4th Plan told me that many things were done during this period of festivities such as the building of roads, telecommunication networks, schools, airports, television stations, hotels and tourist facilities.

But the public fed by the misleading reports in the foreign press and rumours overlooked these facts preferring to dwell on the lavish aspects of the celebrations. Years later some critical historians claimed that the ceremonies in 1971 was the beginning of the Shah’s departure from reality and the start of an era of aggrandizement.

“Did the events in Persepolis cause the revolution in Iran?” I asked.

“I don’t think so,” came the reply. “On the whole the celebrations were a success,” Mr Ansari said.

As I pondered his remarks I remembered how those leaders who had not attended the celebrations had quickly made up for their misgivings. The Queen and President Pompidou invited the Shah and the Empress to London and Paris where they were treated royally. In 1972, President Nixon paid a highly publicised visit to Tehran and agreed to give him carte blanche on any military or technological material he required. Ironically, it was not the expenses that proved the Shah’s undoing but rather the sudden influx of petrodollars after 1974 when the monarch pushed OPEC to quadruple the price of oil.

Overnight Iran’s oil revenue jumped from $2.5 billion to $18 billion in the years up to the revolution. Despite impressive achievements in the country, the Shah’s dreams soon turned sour and the masses led by an exiled cleric revolted. The ship of state, bereft of its captain struck a rock and began to sink.

When in 1979 Khomeini forced the Shah into exile a group of revolutionaries tried to wreck the ancient monuments at Persepolis as a symbol of the “evil monarchy”.

Fortunately, it was the poor villagers and the nomadic Qashqai tribesmen of Fars province who live near there who saved Persepolis from being razed to the ground.

Today both Persepolis and the Royal Tents are still standing generating much needed revenue to Iran’s battered tourism industry.

Ironically, three decades after the Shah’s visit to Persepolis, President Khatami, a reformist cleric and a former revolutionary, came to the site on January 15th 2001 and called for its restoration reminding reporters that the “Persians were once a powerful and ingenious people.” It seemed that he too, like the deposed emperor had fallen under its spell. Persepolis was never meant to be an ordinary place.

We had spoken for three hours. Mr Ansari rang his daughter and asked her to come and fetch him. In the intervening minutes he spoke of his personal feelings about the Shah.

“HIM was a true patriot,” he said confidently. “I have no doubt about it. The day HIM left Iran I was in France with a friend having coffee in a small place beside the Chateaux of Versailles. There was a radio news flash and we heard that HIM had left Tehran after an emotional farewell at Mehrabad airport. It was a terrible day for us. Several weeks later I flew out to Morocco to meet HIM in exile. During an audience I asked HIM what had happened for us to end up like this away from our beloved country. HIM looked at me bitterly and said that he had been betrayed. Later in June 1979, I visited HIM in Mexico. HIM was staying at The Villa des Roses in Cuernavaca with the Shahbanou and the royal children. Once again I asked HIM what had gone wrong. HIM told me that he was busy writing his memoirs and all would be revealed in due time.”

But when the hastily written book eventually came out there was no mention of the Persepolis event.

Tragically, Mohammed Reza Shah, the last of a long line of Persian monarchs, ended his days like a modern version of the Flying Dutchman. When the Shah left Iran on January 16th, 1979, he could find refuge in no port and seemed cursed to wander forever. He went to Egypt, to Morocco, to the Bahamas, to Mexico, America and Panama. But no one wanted him to stay; he was a reject, a pariah, a figure to whom very little world sympathy attached, and virtually no government wanted to risk the angering of the fanatical ayatollahs.

All the courting of a few years earlier, all the flattery, the ingratiation, the respectful premiers and supplicating cabinet ministers from the industrial nations, the bowing and scraping around the world it was as if none of that had ever happened.

While Iran burned in the flames of revolution, the Shah closed his eyes forever in Cairo on July 27th, 1980 in an Egyptian military hospital facing the Nile. He died surrounded by his family and a few loyal members of his entourage and entered history as probably the most misunderstood leader in the 20th century.

Amazon Honor SystemThere was a knock on the window and Mr Ansari stood up and shook hands as we thanked each other.

Before he left I asked him why he hadn’t told anyone his version of the events at Persepolis.

Mr Ansari stared at me for a long while. “Nobody wanted to hear,” he said shrugging his shoulders. “But maybe now with the passage of years it is time to break our silence.”

I lingered on for a while in the café and wrote down my story fully aware of the controversy it would generate.

And as I returned to the rain-swept streets of Paris, the poetic lines of Christopher Marlowe whispered to me, “Is it not fine to be a King and ride in triumph in Persepolis?”