Who do you think you are? The esteemed Indian ancestor no one in my white British family knew about

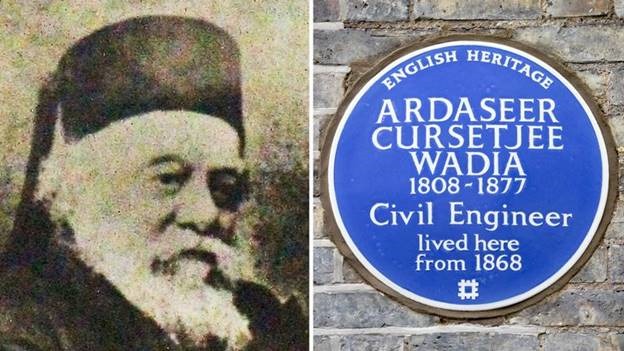

Image: Ardaseer Cursetjee, the first South Asian Fellow of the Royal Society, has been awarded a blue plaque from English Heritage

Today, a blue plaque will be unveiled on a west London house to a man they describe as “the first modern engineer of India”.

The plaque is part of a series in which English Heritage has set about trying to promote the under-recognised historical contribution to Britain of people from diverse communities – by marking the houses where they have lived, as hundreds of white historical figures have already been.

Article by Philip Whiteside | Sky News

Others in the series who also now have blue plaques include Reggae legend Bob Marley, Noor Inayat Khan, a wartime special operations agent, Ottabah Cugoano, an author and anti-slavery campaigner, and the physicist Abdus Salam.

It is a special moment for me because Ardaseer Cursetjee Wadia – the latest person from a diverse community to get a plaque – was my great-great-great grandfather.

It is also particularly poignant because he is an ancestor who, until 12 years ago, no one in my family – one we thought was entirely British – knew about.

Ardaseer Cursetjee Wadia now has a plaque in his honour because he was the first South Asian to be elected to the Royal Society, Britain’s oldest national scientific institution, and was subsequently the first Indian to be placed in charge of British workers in the East India Company, where he was chief engineer.

Born in 1808 into an already successful family called the Wadias, who built ships for the East India Company (EIC) in Bombay, he quickly fostered an interest in the latest scientific developments.

He was the first to use gas lighting in Bombay when he illuminated his house and garden and showed it off to the then provincial governor, the Earl of Clare.

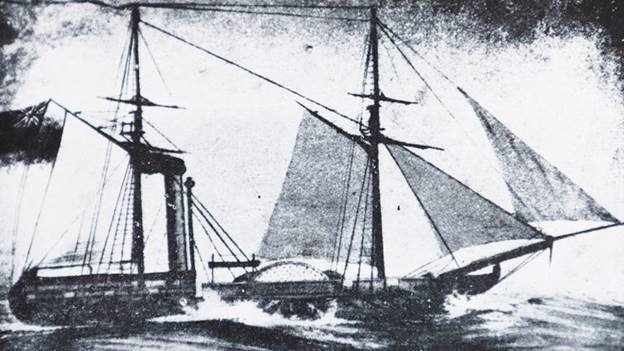

But he was also fascinated by steam power and installed engines of his own design in his family’s ships, at a time when there were very few in use outside of Europe, and pioneered the use of steam to pump water for agriculture in India.

Image: The HSC Semiramis, a steam ship of the type that Ardaseer Cursetjee would have maintained in India. Pic: Philip Whiteside, from The Bombay Dockyard and the Wadia Master Builders, RA Wadia

Steam was the cutting edge of technology at the time and perhaps equivalent to the highest-performance electric vehicle engines, or clean-burning jet engines, of today.

The EIC spotted his talents and in 1839 he was sent to the UK for the first time to improve his knowledge.

Although relatively unknown until recently, his travels to and around early-Victorian Great Britain are actually well-documented as he wrote a diary that was published.

He travelled from Bombay, as everyone did at the time, by ship to Egypt, then, overland via Cairo to Alexandria, then through the Mediterranean to London where he rented a house in Poplar, east London.

While in England, he was presented to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at a private reception ceremony in St James’s Palace and gave evidence to a parliamentary select committee, which included William Gladstone and Sir Robert Peel.

Image: Queen Victoria

And it was around this time, because of his prior achievements, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) – the hallowed bastion of scientific progress which had been viewed as the nation’s principal arena for invention and understanding since the 17th century.

Ardaseer attended Royal Society meetings many times, along with the meetings of numerous other scientific organisations, mixing freely with the great and the good of the day.

When he returned to Bombay, he was appointed the chief inspector of machinery (i.e. the head) of the Bombay Steam Factory, responsible for maintaining all the steamship operations at the time for the EIC and later the Indian Navy.

It meant he was in charge of up to 700 men, including “many English” and “a great many” other Europeans. His only superior, by his own account, was the commander-in-chief of the Indian Navy – something unheard of at that time.

I had no idea about any of this until my mother – who had been carrying out family research of the type made popular by the BBC show Who Do You Think You Are? – emailed me in 2009 and told me she had found an ancestor with an unusual name.

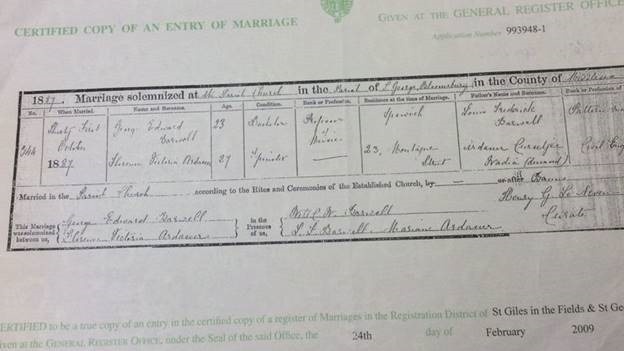

Image: The marriage certificate that identified Ardaseer Cursetjee as part of Philip Whiteside’s family

The man was listed on a marriage record my mother had found as the father of my great-great-grandmother and a quick Google search found details about him on the Royal Society website.

It was something of a surprise – an entirely pleasant one. But, until that point – as I still do – I had answered every question on racial identity on job applications or census returns as “White British”, assuming I had no other ancestry in the family.

It posed a huge list of questions – how could we be descended from not just an Indian, but someone who was relatively esteemed in their day, and not know about it?

In 2012, I decided during a career break to go to India to find out about it, travelling overland as Ardaseer had done, to try to answer those questions.

As it turned out, a distant relative had already been working on getting some answers for some time and was able to fill me in.

Image: The Royal Society headquarters in Carlton House Terrace, St James’s, central London. Pic: Philip Whiteside

The relative, Blair Southerden, found out that Ardaseer was married in India before he left for England in 1839, with Indian children, and lived in Bombay, apparently quite contentedly, for some ten years after returning in 1841.

But in 1851 he returned to England, by his own account on sick leave, bringing with him his son. The exact chronology of where he went during this trip is not fully clear but it is known he crossed the Atlantic to visit Boston, Massachusetts, possibly being among the earliest Indians to do so.

But what was most unclear was how he might have met my great-great-great grandmother, a woman listed in most records as Marian Barber, whose parents lived in Mile End, east London.

Image: Philip Whiteside, on the Italy-Greece leg of his own journey following in the footsteps of his ancestor Ardaseer Cursetjee in 2012

Her family were far from wealthy and most definitely did not move in the same circles as Ardaseer – her father was a messenger in the customs service and they appeared thoroughly working class.

What Blair had managed to find out, and later had published in the journal Genealogist, was that Marian and Ardaseer had three children, the first in late 1853, called Lowjee Annie – partially after the founder of the Wadia dynasty Lowjee Nusserwanjee – the second in 1856, and the third, my great-great-grandmother Florence, in 1859.

What was also intriguing was that the first two children were born in Bombay and Florence was born near to the Royal Courts of Justice in central London.

Blair had been told that Ardaseer returned to Bombay in February 1853, apparently taking with him, according to one historian, equipment for wood cutting. After the trip, he is also said to have introduced photography and electroplating to Bombay.

Image: Bombay’s wharf, where people arriving from the UK would disembark. Pic: Philip Whiteside, courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, India

The best theory as to how Marian could have crossed paths with Ardaseer and formed such a close relationship was that she may have been his nurse, as he had some ailments at the time, or had met him on one of the voyages to or from London.

Despite two weeks in Mumbai (previously Bombay), I was unable to shed any light on how they met, but I carried on researching when I got home.

At the time, large amounts of printed documents and newspapers were being digitised, which was making historical research available to amateurs like myself.

Eventually I found a series of entries in journals of the time that showed he had stayed in England longer than we had previously thought and would have been in London around the time when Ardaseer and Marian’s first child was conceived.

Among them was another pair of Hansard records that showed him giving evidence to both House of Lords and Commons select committees in March 1853, to panels of Lords and MPs including Benjamin Disraeli.

Image: Ships being constructed in the Bombay Dockyards in the 19th century. Pic: Philip Whiteside, courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, India

The records I found showed it was his servants that returned home in February 1853. Perhaps he had stayed on to give evidence to parliament, leaving him without anyone to help at home.

The most logical conclusion to me was that Marian, as a local working class woman – who we had been completely unable to locate on any censuses up until that point – must have had sought employment, perhaps as a housemaid, and ended up being taken on by Ardaseer until he left the UK.

It’s speculation but the rest, as they say, is history – or at least family history.

Marian somehow moved to Bombay and they clearly continued their relationship – how secretly we shall never know. How difficult she found it we will also never know, but if she was kept secret it must have been extremely isolating for her – bringing up two children in the back-streets of Bombay, unable to integrate with the rest of society.

Image: Bombay’s harbour during the period of control by the East India Company. Pic: Philip Whiteside, courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, India

She returned to London in 1859 and, it appears, Ardaseer did too, around the same time.

It could have been an unhappy story; so many stories from that time feature men who abandon women who they have relationships with.

Thankfully, this one was not.

Despite having an Indian family – including several children who went on to found successful businesses in Bombay and grow very rich – he set up home in London, appearing on the census several times after that with Marian and their children. Periodically, it appears he returned to Bombay, possibly for work, but probably to see his Indian family.

His last location was in Richmond, at the house he also named after his dynasty’s founder.

Thanks to Blair, who put forward Ardaseer Cursetjee Wadia’s name to English Heritage, that house – at 55 Sheen Road, Richmond upon Thames – had the plaque installed on Tuesday that showed he made it the home that concluded his British legacy.

Image: The blue plaque to Ardaseer Cursetjee Wadia, on the house at 55 Sheen Road, Richmond, London

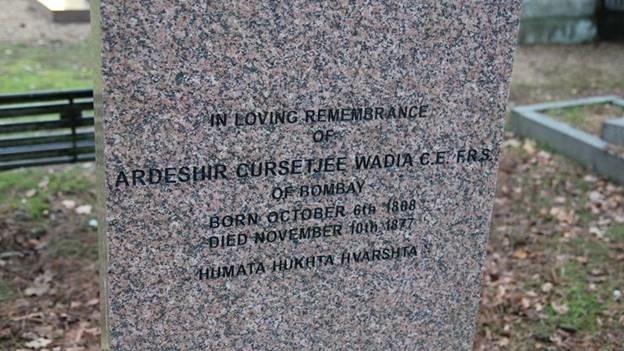

Ardaseer died in 1877, leaving a will acknowledging Marian’s children as his own and was buried in Brookwood cemetery, Surrey.

Whether his other, British, family and departure for England had an impact on his legacy in India is hard to determine.

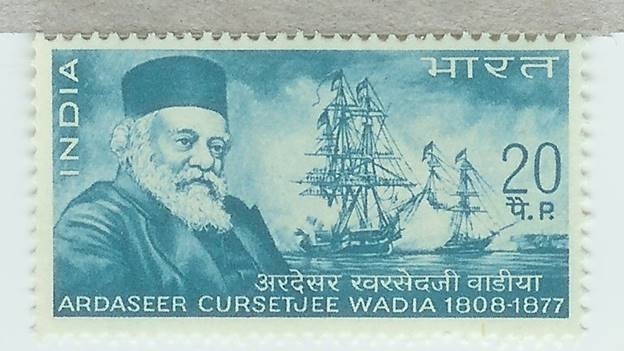

He was commemorated in 1969 in India with a stamp but at the time I started my research was not widely known as the first Indian FRS, with some in India writing on blogs they believed a mathematician called Srinivasa Ramanujan held that honour.

Image: Ardaseer Cursetjee, featuring on an Indian stamp from 1969. Pic courtesy Blair Southerden

His Indian direct descendants are the Wadia dynasty, some of whom head up a firm worth billions of dollars. Today, they are on India’s rich list.

It’s perhaps less hard to fathom why Ardaseer’s name remained unknown to my family. As well as my immediate relatives, Ardaseer has dozens of other descendants living in the UK.

While it is difficult to accept there may have been racism in anyone’s family in the past, it undoubtedly existed widely at that time. But, even if it was not buried because of racism, Ardaseer’s daughter Florence later suffered a mental illness that led to her being institutionalised in an asylum – something that could have been influenced by attitudes to people of dual heritage at the time. Consequently, hidden from society until her death many years later, she became forgotten, or at least unspoken about.

Image: Lowjee Nusserwanjee Wadia, the founder of the Wadia dynasty, Pic: Philip Whiteside, courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, India

But, besides the story of Ardaseer’s family being a fascinating insight into the past, his getting a plaque is doubly satisfying because it underlines the achievements of a man who has been long overlooked.

English Heritage’s Dr Rebecca Preston, who carried out the research confirming the location of his house, says he was remarkably pioneering for his day.

She told Sky News: “He was very clever, very passionate, and although he trained to be a marine architect, it was steam that really drove him. Obviously, he’s most associated now with applying steam to ships.

“He also used steam engines for agricultural purposes in India but the advancement of steam-powered navigation is his key legacy. But his interests spread, and he introduced gaslight, electroplating, photography and various other new technologies to India.”

Image: The grave of Ardaseer Cursetjee at Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey. Pic: Philip Whiteside

“He’s at the forefront of advancing science and engineering in modern India, I think.”

What his and my story may also hint at is how many other people may have ancestors in their lineage that may surprise them.

Dr Preston adds: “The very fact of (Britain) having an empire and it being a seafaring nation meant that it was possible for people to mix with people from other places (and there may, as a result, be many of mixed heritage).”

“As to how many, I couldn’t say, but I’m sure this must be the case, going back hundreds of years.”

Part of the reason for English Heritage’s call for more figures from diverse communities to be nominated for plaques is to recognise how many in the past played significant roles and were present in British life, even if this has been hidden from history or they are overlooked today.

Dr Preston added: “We rely on the public to nominate notable individuals for a blue plaques, we don’t do the nominating.

“So hopefully, as more are suggested, we’ll be seeing more people of colour, of mixed heritage being recognised with a plaque on buildings in London where they lived or worked.”