Mumbai’s Irani cafés are an iconic part of the city’s social fabric, but over time, they have rapidly decreased in number. An homage to days of old, these cafés represent all that is cosmopolitan about Mumbai, carrying forward a centuries long tradition of inclusivity, simplicity and indulgence.

Written by Mira Patel Indian Express

While there were once over 300 cafes in Bombay, today, fewer than 25 remain.

A hot cup of chai with a bun maska or a bowl of Dhansak with steamed rice on a lazy Sunday afternoon. If you are in Mumbai, this would be a familiar sight at the iconic Irani cafes of the city. Clad in unassuming yet recognisable décor and enveloped by the smell of freshly baked bread, these cafes symbolise Mumbai’s cosmopolitan nature, providing people from all walks of life with a place to relax, socialise and indulge.

Littered across the city, but most common in the commercial Fort district, Irani cafés are steeped in nostalgia but are now fast disappearing. While there were once over 300 cafes in Bombay, today, fewer than 25 remain.

History of the Irani community in Bombay

Until the 1947 Partition, India and Iran shared a common border and the two countries had deep cultural, political, and economic ties. Nile Green, a professor at UCLA, in his book Bombay Islam writes that “in 1830, Bombay’s total trade with Iran amounted to 350,000 rupees, but by 1859 the annual trade in horses alone had risen to 2,625,000 rupees, and this trend continued as the century progressed. By 1865 the number of Iranians officially registered as residing in Bombay reached 1,639 persons, though we can be fairly sure that a good many more unofficial residents escaped the eyes of the city’s officials.”

Irani refers to people from the country of Iran (formerly known as Persia) and includes people from both Parsi and Muslim faiths.

In the 7th century, the Zoroastrian Sassanid dynasty in Persia was overthrown by Arab Muslims under the Rashidun Caliphate. Fleeing religious persecution, the Zorastrian Iranis sought refuge in India in several waves. The Parsi community arrived in the subcontinent almost 1,000 years ago, settling north of Bombay, primarily in Gujarat. As Bombay’s fortunes grew, the Parsis slowly began to abandon their roots in Surat and Ahmedabad, opting instead to immerse themselves in the chaotic and lucrative ecosystem of the country’s financial capital.

The early Parsis contributed significantly to the city’s development, engaging in local politics, dominating industry, and setting the bar for philanthropic initiatives. In 1854, a Parsi named Dinshaw Maneckji set up a fund to help Zoroastrians in Iran join the thriving Parsi community in Bombay. The people in this wave of immigration came to be known as Iranis, and they subsequently established most of the Irani cafes from the 19th century onwards.

Although the Parsi community dominated the café scene, and Irani cafés are often associated with them, some of the city’s Irani cafes have been operated by Shi’a and Baha’i Iranis as well.

Simin Patel, the founder of Bombaywallas, a website dedicated to uncovering the secrets and overlooked gems of the Maximum City, says that for the Parsi immigrants, the cafes represented a form of upward mobility. She says that initially, immigrants would work in the homes of Parsi families, later rising to the position of kitchen staff and then eventually taking over a share of the business.

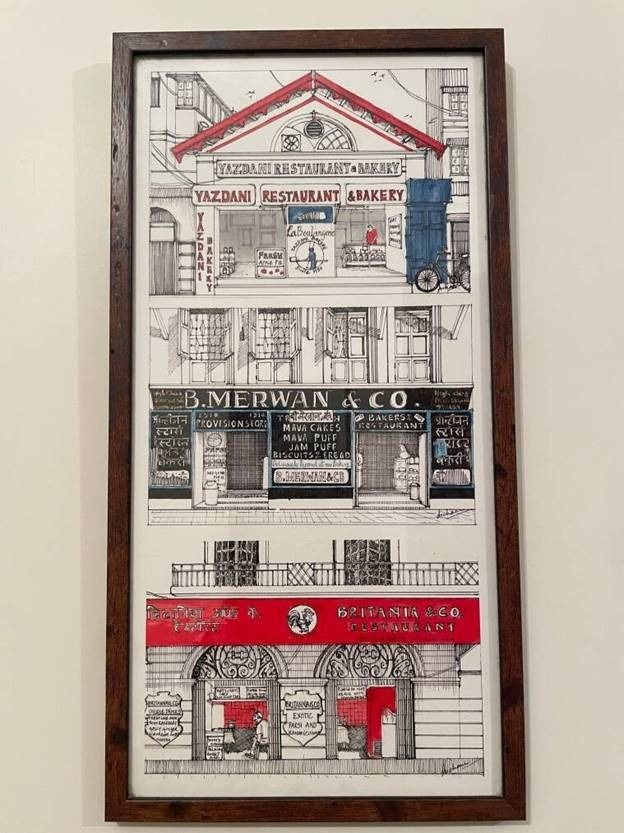

Yazdani, B Merwan and Co, and Britannia (Photo by Mira Patel)

As Aflatoon Shokriye, owner of Kayani and Co., tells Irani Chai, a website that records the oral history of Irani cafés, almost all the Irani migrants opted to work at these cafés. He says, “it was an institution, like Iranis, what you call it, it was like a training college!;they used to come and learn business, how to prepare, how to do business, and other things, and they used to go and make partnership with others and start their own business, set up their own Irani café.”

But why did they start the cafes in the first place?

According to Sifra Lentin, a fellow at Gateway House, immigrants from Iran (both Shi’a and Zoroastrian) primarily came from the drought-hit provinces of Yazd and Kerman. These towns were once integral parts of the Southern Silk Route. While its residents were primarily horticulturalists, they were also involved in the opium trade, using the substance to make coffee and black tea. As such, they had prior experience in preparing tea and found a natural home and demand for it in Bombay.

The migration of the Irani community coincided with the heyday of the industrial revolution in India. As the city grew, migrants began flocking to its shores. These migrants, poor and often overworked, needed a cheap and accessible place to grab an early morning tea or a late afternoon snack. Working in the mills and the docks, they became the earliest proprietors of the Irani cafés.

A typical blackboard with a list of rules at Cafe Irani Chaii of Mahim (Photo by Aakriti Chandervanshi)

The café owners were also incentivised by economic conditions. Hindu merchants believed that corner properties were inauspicious and that no matter how much revenue they generated, their owners would never see prosperity. As a result, they tended to rent those properties out cheap to the Irani community.

Café Culture

In the heydays of the Irani cafés, Bombay was very much a segregated city. Indians were banned from entering places like the Bombay Gymkhana and the Royal Yacht Club. Places that did welcome Indians, like Jamshedji Tata’s Taj Mahal Hotel, were often unaffordable for the common citizen.

Cosmopolitan is located prominently at the junction of Sandhurst Road and New Queen’s Road (Photo by Aakriti Chandervanshi)

Religion was another dividing force. Muslim institutions tended to cater only to Muslims, as did Catholic and Hindu restaurants as well. In contrast, the Parsi community tended to adopt a more inclusive approach.

Patel says that “the (Irani) cafés provided an inclusive space for people of all backgrounds and religions, allowing even women and children to have more freedom by creating family rooms and cabins for them to dine in.” As a result, they became Bombay’s first public eating places that were welcoming and affordable to all.

In terms of affordability, the prices at these cafés still cannot be beaten, At Roshan Bakery and Restaurant for example, a cup of Irani chai costs Rs 20, significantly lower than what one would pay at a coffeehouse chain.

As journalist M G Moinuddin wrote in the Illustrated Press in 1986, “devoid of any hoity-toity airs, people from all walks of life patronised these quaint restaurants…for most, they became places for social rendezvous, a kind of poor-man’s roadside parlour where secrets and sorrows could be shared along with a leisurely cup of tea.”

Sassanian Boulangerie (Photo by Aakriti Chandervanshi)

In keeping with that inclusive approach, the food and drinks served in these cafés were not authentically Iranian, instead incorporating elements from Goan, Gujarati and Mughal cuisine. In Iran, people traditionally drank their tea without milk and opted for flatbreads instead of the buttery brun that characterised breakfast at the Irani cafés.

For Gateway House, Lentin writes, adaptations such as brun and pao, evolved from the Dhobi Talao locality where the first Irani café, Kayani and Co, originated. As Dhobi Talao was primarily home to Goan Christians who took these Irani immigrants under their wing, the food in turn adopted a distinctly Goan flavour.

Mirza, son of Agha Nazariyan, at the counter of Cafe Colony at Dadar (East)(Photo by Aakriti Chandervanshi)

Similarly, the food also incorporated a strong Gujarati influence. Papri Ma Gosht (baked beans with mutton) and Chora Ma Gosht (black eyed peas with meat) are both non-vegetarian versions of traditional Gujarati dishes. Gujarati food also tended to favour sweetness, an element that was also passed down to Irani fare.

Perhaps the best way to summarise the distinct culture of Irani cafés is found in a poem written by the late Indian poet and actor, Nissim Ezekiel in 1972. Titled Irani Restaurant Instructions, Ezekiel writes:

Please

Do not spit

Do not sit more

Pay promptly, time is valuable

Do not write letter

without order refreshment

Do not comb,

hair is spoiling floor

Do not make mischiefs in cabin

our waiter is reporting

Come again

All are welcome whatever cast

If not satisfied tell us

otherwise tell others

GOD IS GREAT

Food, Décor, and Institutions

Irani cafés are characterised by their distinct, no-frills décor. They tend to feature chequered floors, large mirrors, high ceilings, red and black checked tablecloths, and straight backed wooden chairs. Additionally, no café would be complete without a tiny army of wait staff, running frantically from table to table, as their proprietor barks orders at them.

Biscuits and confectionery, neatly arranged on the shelves of Kyani and Co. (Photo by Aakriti Chandervanshi)

In terms of food, the cafés take a simple yet flavourful approach. Parsis are known to eat meat for breakfast, a tradition born from necessity with poor Parsis often eating leftover dinners the next morning. They also tend to favour eggs, particularly during breakfast, but also as an accompaniment to practically every and any dish. Arrive at one of the Irani cafés at the break of dawn and expect to be greeted with the city’s finest maska buns and Irani chai.

At lunch, dishes like sali boti, a lamb curry stewed with tomatoes and onions, and berry pulao, a combination of moist chicken and rice, reign supreme. These mouth-watering meals are usually accompanied by a sweet raspberry soda or a sharp, fresh lime soda.

The holy grail of Irani cuisine is reserved for lazy Sundays. On a day where there is no agenda but to eat and sleep, one could find few better options than Dhansak, a lentil-based spicy dish served with mutton and berries.

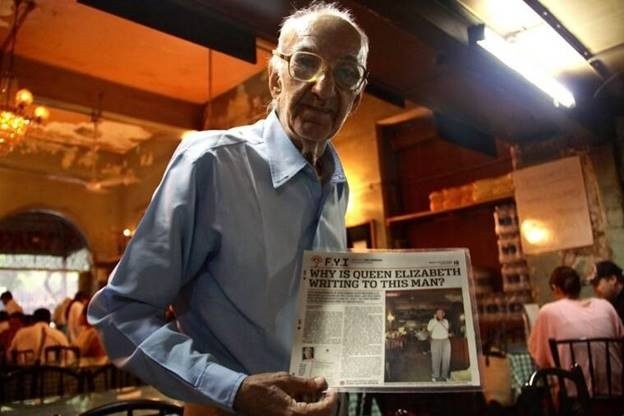

Boman Kohinoor, the late owner of Brittania Cafe (Photo by Rahul Patel)

Many believe that the best Dhansak in the city is served at Britannia cafe in Mumbai. Started by Roshan Kohinoor in the pre-independence era, Britannia is run and managed by the third generation of the Kohinoor family. The restaurant is known not only for its delectable food and quaint ambiance, but also for its late owner, Boman Kohinoor, who even at the age of 97, continued to greet customers personally. Kohinoor’s café was frequented by many distinguished personalities, including Prince William and Kate, and even received a letter of appreciation from the late Queen Elizabeth.

Yazdani bakery, in Fort, with its red roof and pale blue exteriors is another popular haunt. Known for its bread pudding, apple pie and Shrewsbury cookies, Yazdani retains many of the early practices of Irani cafes. Its staff work 24/7, sleeping on top of the café’s wood fired ovens during their time off, and baking fresh breads and cakes during their time on.

As its owner, Zend Meherwan Zend, tells Irani Chai, there is beauty and expertise in even the simplest of practices. Yazdani is one of the only bakeries that employs the sourdough process instead of using readymade yeast, as is the norm today. He says that using hops in the baking process prevents unwanted bacteria from spoiling the dough, keeping the bread fresh days after it has been prepared.

“The so-called ‘American’ bread that some people like these days contains at least five to seven different types of chemicals to make it soft and white and have a longer shelf life. How can you expect that biochemical mass to be digested by your system?”, he asks. “Bread must have a bite to it. In India we need bread which will maintain its structure when you dip it into gravies and sauces. Soft bread dipped in dal or tea would simply flop or disintegrate.”

Decline of the cafés

The cafés reached their peak in the 1960s before slowly beginning to close down. This coincides with the decline of the Parsi population as well. By the mid-20th century, around 120,000 Parsis lived in India. Today only half that number remains. Furthermore, those who are still around often don’t want to enter the restaurant business because of its unforgiving hours and tiny margins.

As Patel notes, “competition, ownership problems, and the reluctance of present generation Iranians to carry on the family business are contributing to the slow fadeout of these proud cafes.” She says that over time, the cafés were replaced by beer houses and later disco halls. Now a lot of them are chain restaurants and high revenue generating institutions as the price of land becomes more valuable in the city.

B Merwan and Co (Photo by Aakriti Chandervanshi)

When liquor permits were introduced in 1972, many of these cafés found it more profitable to convert into beer houses but some stubbornly refused to give up. Instead, they adapted to changing trends, incorporating new items into their age old menus. Leopold and Co, described by author Gregory David Roberts in Shantaram, as a “mystic, dark place…constantly crowded” best epitomises that approach.

While Leopold started as a store selling confectionery items like biscuits, cakes, toothpaste and soaps, it later expanded its offerings to Parsi fare and even beer. Today, it has 140 or so items on its menu, including a wide variety of Chinese dishes that are popular amongst locals.

Another institution keeping Irani café culture alive is the chain SodaBottleOpenerWala. The restaurant chain offers distinct Persian food and features motifs from the original cafés. In a time where Irani cafés are slowly fading out, SodaBottleOpenerWala can be credited for reviving the café culture.

Dishoom by Dishoom Facebook

Internationally too, Irani café culture has taken root. This is largely because of the outrageously popular restaurant Dishoom which originated in London but now has nine locations across the UK. Dishoom is modelled after a traditional Irani café and thrives on its mandate to be inclusive to all.

As documented in its best-selling cookbook by the same name, Dishoom was designed to embody inclusivity.

It states that “we’ve had the privilege of bringing Hindus and non-Hindus together to throw colour at each other with abandon at Holi, and to dance together at Diwali. We bring Muslims and non-Muslims together over food and music for Eid, and Christians and non-Christians together for Christmas caroling.”

Dishoom, like Brittania and Yazdani, recognises that Irani cafés are not just about the food. They are a communal space, accessible to all, that serves as a socio-economic leveler, bringing together young and old, rich and poor, over a steaming hot glass of chai or an indulgent feast of berry pulao.