The 2,400-year-old papyrus from Elephantine, touted as the earliest evidence for Pesach, may in fact reference Zoroastrian-influenced rituals, Israeli scholar concludes

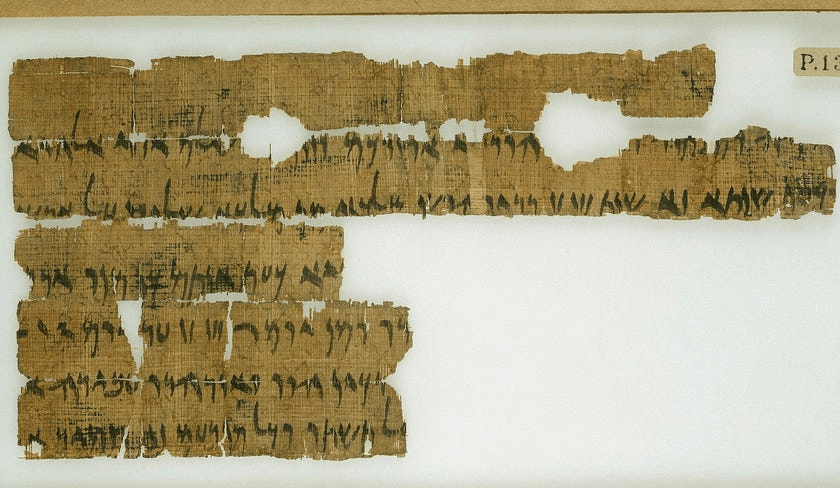

The fragment of the ‘Passover letter’ from Elephantine, 419 B.C.E.Credit: bpk / Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, SMB / Margarete Büsing

Article by Ariel David | Haaretz

Nov 4, 2024 12:34 pm IST

The so-called ‘Passover Letter’ is a tattered papyrus written in Aramaic during the Persian period. It is thought by scholars to contain the first extrabiblical reference to the rituals of Pesach, thus proving that this festival was already well established more than 2,400 years ago.

Not so, says a new study by an Israeli researcher, which calls into question a century of scholarship on the seminal document and claims the text has little or nothing to do with Passover as we know it. Instead, the letter was most likely discussing Zoroastrian-inspired rituals that were commonly observed by Jews in the Persian Empire, says Dr. Gad Barnea, a lecturer in Jewish history and biblical studies at Haifa University.

If correct, Barnea’s hypothesis would have broad implications not just for the nebulous history of this central Jewish holiday but also for what we understand about the origins of Judaism as we know it.

The Passover Letter was discovered in the early 20th century at Elephantine, an island on the Nile in front of Aswan. Dated to 419 B.C.E., it was part of a large cache of texts documenting the life of the Jewish community there throughout the fifth century B.C.E. The community on the island may have been established as early as the late First Temple Period, in the seventh-sixth century B.C.E., as Assyrians and Babylonians overran the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

Under the Persian Empire, which conquered the Levant and Egypt in the late sixth century B.C.E., the Jewish community on Elephantine prospered. It included a garrison of Jewish soldiers guarding the strategic island for the Persians; had its own shrine to Yahweh, and was in touch with Jerusalem and other Jewish centers of the early Second Temple Period.

The Elephantine documents predate the famed Dead Sea Scrolls by some four centuries and are considered an invaluable testimony from the early days of Judaism. In the case of the Passover Letter, it is quite clear that what has survived of the fragmentary text doesn’t explicitly mention the word “Pascha,” the Aramaic equivalent for Pesach.

The letter, sent by one Hananyah (more about him later) to his fellow Jews, includes instructions for a celebration that was to take place between the 15th to the 21st day of the month of Nisan, which does correspond to the dates of Passover. The text also mentions a drink that must be consumed on this holiday – maybe a hint to the wine Jews drink on Passover eve – and makes reference to “anything of leaven.” As a result, most scholars have concluded the letter is the first historical mention of the festival when Jews consume unleavened bread to commemorate the biblical exodus from Egypt.

But Christian and Jewish scholars may have been too eager to see in the letter a confirmation of what is written in the Bible (2 Kings 23:21-23), which states that Passover as we know it was established by King Josiah of Judah in the late First Temple Period, about a century before the Elephantine document was written. Barnea’s study, published in October in a new book of essays titled “Yahwism under the Achaemenid Empire,” calls into question this bias.

“There is so much projection in our field, we project from the Bible onto archaeological findings instead of looking at the findings and letting them speak for themselves,” Barnea tells Haaretz in a phone interview. “If it corresponds to something from the Bible, great, but let the objects speak for themselves, especially when claims of an ‘earliest reference’ are being made.”

Temple on Elephantine Island, Egypt, 2011Credit: Olaf Tausch

Sacrificing to Ahura Mazda

By offering a new translation of the Aramaic text and studying the context in which it was written, Barnea argues that there is no proof that Hananyah’s instructions concerned the celebration of the Passover. Rather, he sees a more likely match between the practices mentioned in the letter and those of Zoroastrianism, the official religion of the Persian Empire, with which Jews at the time had close and documented ties, as we shall see below. Barnea identifies features in the text that are compatible with a “Yasna,” the traditional ritual sacrifice to Ahura Mazda, the creator god of Zoroastrianism.

The drink mentioned in the letter could well be “Haoma,” a plant-based drink that is part of the Yasna ceremony, Barnea writes. The mention of “anything leavened” may in fact refer to the “Dron,” the main offering of the Yasna ceremony, he says. In Zoroastrianism, this was initially a sacrificial animal and later (though we don’t know exactly when) it became a loaf of unleavened bread, very similar to the Jewish matzah consumed on Passover.

And while the dates of the celebration mentioned in the letter match those of Passover they could also be marking a seven-day festival that followed the first full moon of the year, which coincided with the beginning of the harvest and was observed across the ancient Near East, Barnea says. In the Persian Empire, the year started on the first of Nisan, for Jews and non-Jews alike, and thus the week of the 15th marked the first full moon.

“In agricultural societies, the harvest determines whether you live or die, so it’s a very important time,” Barnea says. “A heptad, a period of seven days, is a symbolic period in Zoroastrian traditions. It was very common to keep a holiday on the first full moon of the year, so as to appease the deities who might destroy the harvest and then go ahead and harvest the crops.”

And finally there is the matter of the letter’s author. Traditional scholarship identifies Hananyah as a priest in Jerusalem, possibly even the brother of Nehemiah, the governor of Persian Judea and rebuilder of Jerusalem. But that identification is unlikely, Barnea avers.

The writer of the Passover Letter takes pains to stress that he is writing “in ‘this year,’ the fifth year of King Darius II,” which translates to 419 B.C.E. in our calendar.

But for this statement to be correct, the letter must have been written after New Years, which, as mentioned, back then fell on the first of Nisan, just a couple of weeks before the start of the mysterious celebration that Hananyah was discussing. This means there would have been only a handful of days for the letter to travel all the way from Jerusalem to Elephantine in Upper Egypt, Barnea notes. It is instead more likely that the letter came from a Hananyah who is known from other texts of the era as being a Jewish high-ranking official for the Persians in the provincial Egyptian capital of Memphis, he argues.

Elephantine Island, west side, EgyptCredit: Przemyslaw “Blueshade” Idzkiewicz

The Bible is the exception

It should be noted that, due to a paucity of surviving documents, we don’t know much about Zoroastrianism in the Persian Empire during this ancient period, cautions Prof. Domenico Agostini, an expert on ancient Iran at the University of Naples “L’Orientale,” who was not involved in the study.

“There is even an open question as to whether the Achaemenids, the dynasty that ruled the empire, were only worshippers of Ahura Mazda or already Zoroastrians,” Agostini says. “However, Barnea’s study has the great merit of recognizing the important role that Zoroastrianism played in the cultural transformations that occurred across the empire.”

But why, you may ask, would Jews in Elephantine be following Zoroastrian traditions and taking instruction on religious matters from the Persian administration? Well, most scholars agree that through the First Temple Period, and possibly well into the Second Temple Period, the Israelite religion was very different from what we know today. Torah law was not yet observed and neither was monotheism: while the Israelites worshipped a god named Yahweh, they also believed in other deities.

Some of these gods are also mentioned in other documents from Elephantine, such as Anatyahu, possibly a consort of Yahweh. In the Passover Letter itself, Hananyah invokes the blessings of “elahayah” (the gods – in the plural) upon his readers.

So the Judaism of the Persian period was still very different from the religion we know today, and we have no evidence that by the fifth century B.C.E. Jews had any knowledge or observance of basic precepts of the Torah, such as monotheism or kosher laws, or the keeping of Passover, Barnea says.

We do know instead that there was a lot of Zoroastrian-inspired syncretism across the Jewish world, with Yahweh taking on attributes and forms of veneration typical of Ahura Mazda, he adds. Zoroastrian priests, known as magi, and faithful were present at Elephantine and nearby Aswan, and had close ties with the Jewish Yahwists. More importantly, another papyrus in the Elephantine cache mentions that in their temple, the Jews maintained a “fire altar,” something alien to later Jewish tradition, but a central form of veneration in Zoroastrianism.

“This is not surprising. Everyone was assimilating features from each other and it was not a big deal,” Barnea notes. “That’s just how people operate around the world: you come in touch with a faith system and you translate parts of it into your own system, especially when the other religion is the dominant one.”

We might be tempted to think that the Yahwistic Jews of Elephantine were some kind of heretical aberration, but there is no evidence of that. As Prof. Reinhard Kratz, a leading German biblical scholar from the University of Göttingen, put it in a 2006 book: “The Bible is the exception, not Elephantine.” For example, after their temple was destroyed in 410 B.C.E. during an Egyptian revolt against the Persians, the Jews of Elephantine successfully petitioned officials in Judea to allow them to rebuild their sanctuary. Evidently, nothing in the cultic practices at Elephantine was opprobrious to the Jews of Jerusalem. And that’s despite the fact that the very existence of a shrine in Elephantine seemingly flies in the face the biblical injunction to centralize the worship of Yahweh at the Temple in Jerusalem (Deut. 12:5-14).

A merger of feasts

The fact that the biblical precepts were either broadly ignored or not yet existent at this time further increases the likelihood that the ritual instructions sent by Hananyah concerned some form of Zoroastrian-influenced celebration, rather than Passover itself, Barnea says. It is true that the Aramaic term Pascha appears in other Elephantine documents, but, again, it does not seem to be connected to the known rituals of Passover or its biblical backstory of liberation from bondage in Egypt. Instead, the mentions of Pesach refer to a ritual against the “evil-eye” connected to stressful situations, such as a plea for the protection of infants, he says.

To some degree, this dovetails with something that scholars have long suspected about the history of Passover. This festival apparently emerged from the fusion of at least two other religious observances. One was the original Pesach, an apotropaic ritual to ward off evil, similar to what is described in the other Elephantine documents. The second was the Feast of Matzoth, or Festival of Unleavened Bread, which marked harvest time. At most, it is possible that the Zoroastrian-inspired rituals described in Hananyah’s letter formed a precursor to what would become the Feast of Matzoth, Barnea speculates.

When and why these two festivities – Pesach and the Feast of Matzoth – were merged and linked to the biblical narrative of Exodus remains an open question. But if Barnea’s interpretation of the Passover Letter is correct, then this process happened much later than many scholars believed. Passover may have taken its final form in the Hellenistic period, in the late fourth or third century B.C.E., or perhaps even later, under the Hasmonean dynasty that ruled Judea from the second century B.C.E., which may have been eager to transform agropastoral holidays into a major national festival of liberation, Barnea proposes.

“The long-lived scholarly consensus which has linked this papyrus with Passover or the Festival of Unleavened Bread is based entirely on highly speculative reconstructions of the missing portions of the document,” comments Prof. Yonatan Adler, an archaeologist from Ariel University who was not involved in this study. “It is also rooted in the faulty assumption that the laws of the Torah were well-known and widely observed among Jews as early as the fifth century B.C.E. It is high time that this idea is finally laid to rest and Barnea’s work provides an important contribution toward dispelling the myth that Torah-observant Judaism existed so early.”

For his part, Adler has extensively investigated the archaeological evidence for the origins of Judaism. In a recent book he too presented data showing that the development of Judaism was a much slower and complex process than previously believed, and that many of the beliefs and rules we consider cornerstones of the religion were a relatively late evolution, coalescing into canon perhaps just about a couple of centuries before the birth of Jesus.

“The point is that all religions are dynamic, they change, they evolve, they get into give-and-take relationships with other religions and ideologies,” Barnea concludes. “They are never fossilized, and Judaism was certainly not fossilized in antiquity.”