Meher Marfatia: The Benevolent Businessmen From Aden

The Cowasjee Dinshaw Collection of the Adenwalla Archive reveals rare records of a family of merchant-princes, last of the philanthropic Bombay sethias, who fronted the golden age of Parsis in Aden

Article by Meher Marfatia | Mid-Day

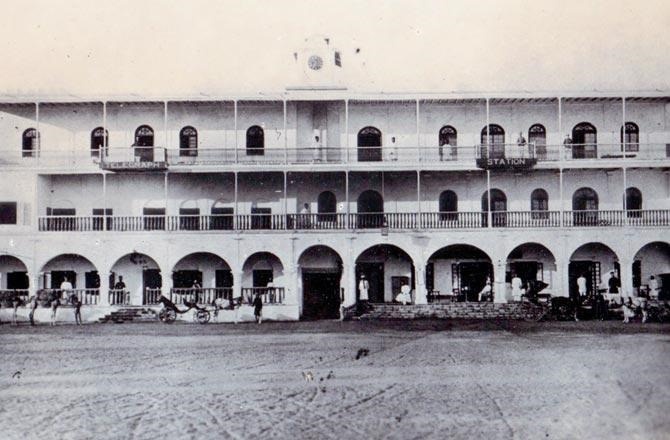

Aden House, the Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. building

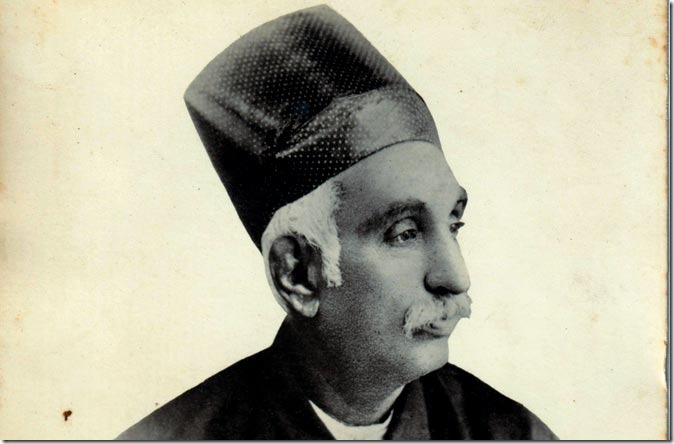

They were the uncrowned kings of Aden in an age of Empire. Tempering entrepreneurial acumen with gentle philanthropy, Cowasjee Dinshaw (1827-1900) and his heirs dominated commercial and civic life of this port city, located strategically in the Arabian Peninsula at the south of present-day Yemen.

If significant writings track the Parsi trade with China, we have scant profiles of pioneers venturing to the Middle East. The Cowasjee Dinshaw Collection, inaugurating the Adenwalla Archive, is offered by Bombaywalla Historical Works, historian Dr Simin Patel’s organisation. Vast and visually captivating, it frames the fortunes of an illustrious clan transforming Aden from sleepy sandscape to the Crown’s busiest transit hub with 80,000-ton oil tankers passing through.

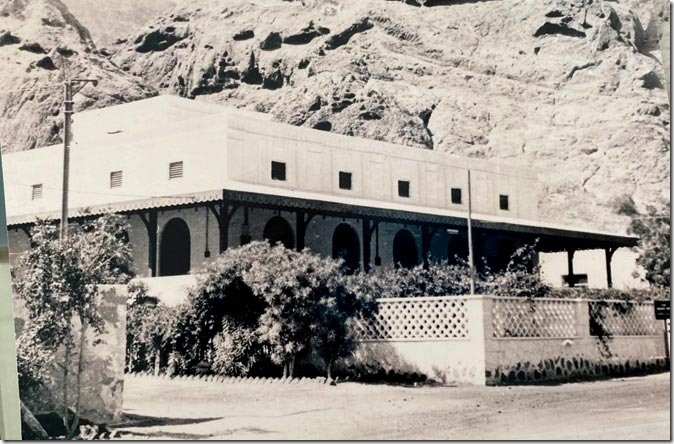

The Cowasjee Dinshaw Agiary built for the port’s Parsi immigrants was funded by its benefactor in 1883. Pic courtesy/Soli Daruwalla

Arriving in Aden from Bombay in 1845, Cowasjee worked for Muncherjee Eduljee Sopariwalla & Sons, where his father Dinshaw was manager. Within five years he braved it solo, providing the garrison and government basic supplies from a thatched hut in Crater, the dormant volcano site he rode to on a donkey, sometimes a pony. Realising the potential of a modern port, with sagacious vision he proceeded to remodel it for traffic between the Indian Ocean and Europe.

Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. was set up in 1854. Cowasjee was principal partner, with his brothers Dorabjee and Pestonjee partners in their office at Steamer Point, Tawahi, on the harbour. Emerging renowned ship chandlers, they capably controlled military, naval and livestock supplies, launched sea routes for communication networks, ferried travellers between Aden, Perim and the Somali coast. When the Suez Canal rose in 1869, the British India Steam Navigation Company hired this firm as Aden agents. The Cowasjee Dinshaw, Bhicaji Cowasjee and Shilay Yehuda emporiums were main attractions along Crescent arcade of Steamer Point.

Portrait of Cowasjee Dinshaw, the founder patriarch of 19th-century Aden’s leading business house

“The archives preserve an important slice of the history of Parsis in Aden,” says Parsiana editor Jehangir Patel, Cowasjee’s seventh-generation descendant and Simin’s father. “We discovered photos and documents in iron trunks in godowns and storage rooms.” Focused on Cowasjee’s community-consolidating activities, these examine his pivotal role as the contributor and custodian of such assets as a fire temple and funerary tower.

The wealth willingly reserved always for public good, facilities for the local population included a mosque and medical dispensary for Tawahi’s poor.

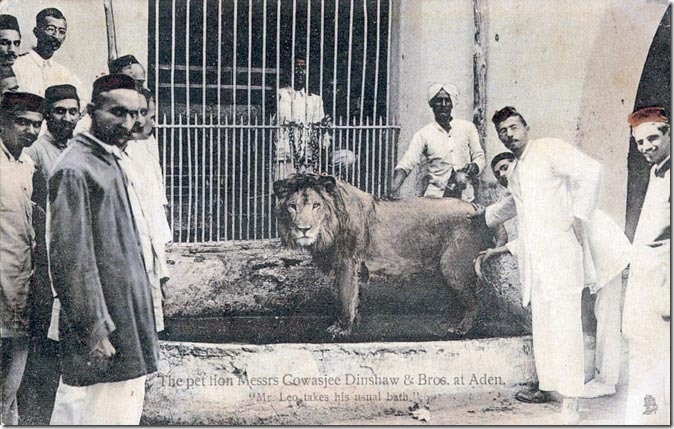

Postcard captioned “Mr Leo takes his usual bath”. The Adenwallas were gifted the African lion as a pet cub by one of their sea trading partners. Pics Courtesy/Bombaywalla Historical Works

Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. recruited boys from Bombay and Gujarat. Shiavax Bokdawalla of Navsari was picked as a 17-year-old in 1943. His sons, Jamshed and Sarosh, reveal three generations of their mother’s family were Aden-born. “Weekly outings were to Gold Mohur Beach or Prince of Wales Pier. Going on to work with Noshir Motivala’s Allied Agencies, our father finally started his own Mazda Stores in Malla, selling provisions and liquor,” Jamshed recalls. The republic forming in 1962, South Yemen remained with the British as the Aden Protectorate until 1967, when it became independent.

“Revolts caused conditions to deteriorate terribly. Dad came to Poona with just the clothes he wore,” says Sarosh Bokdawalla.

Those were heavy-hearted homecomings. Fleeing the ravages of civil war, wrought by armed insurgents from the Radfan mountains, among the last to leave, Noshir Tangri exited Aden with mixed relief and regret—”Memories of my father’s establishments, Star Pharmacy and Ice Factory, make me miss the prestige we enjoyed.”

That heyday had followed the finest hospitality template laid by Cowasjee. Designated a Companion of the British Empire (CIE) in 1894, he felicitated viceroys, dignitaries and even the Prince of Wales in 1875 on his passage to India. His heirs as readily entertained touring members of the community. With the canal, the advent of steam-powered ships and maritime surge, the number of Parsi visitors upped. Informed of these sojourns, the Aden sethias welcomed them warmly with invitations to grand meals.

“Parsis residing overseas graciously greeted their brethren,” says Jehangir Patel. “Ships anchoring at a distance, passengers boarded launches to reach port. They looked forward to duty-free shopping in Aden.” One of his trips was in 1953, en route west on a P&O liner and in 1955 aboard an Anchor Line steamer to India. “On my last visit in 1964, westward on a Lloyd Triestino steamer, a special launch fetched me courtesy Dinshaw H Dinshaw, Cowasjee Dinshaw’s grandson, the grandfather of Kaikobad and Dadi Pudumjee, and last family member in Aden. Co-passengers were duly impressed when my name was announced on the public address system.

“My maternal grandfather, Nusserwanjee, Dinshaw’s younger brother visiting at the time, was in the hospital, knocked down by a car while crossing the road. After meeting him, I had lunch with Dinshaw and his lawyer Mansoor. At the department store run by Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. I bought an Underwood or Olivetti portable typewriter. There were no fancy display racks but durable items one wished to purchase were surely there. I never heard anyone complain of not getting what they wanted. Compared to socialistic India, this was a consumer’s paradise.The parts I visited had not many structures, the desert appeared all around. The place had a laidback, languid air and was appealing,” he adds.

In dry Aden, with 45-degree summers, about 1,300 Parsis in peak years lived alongside 30,000 Gujaratis, Sindhis and Punjabis. Among other desi tycoons groomed by Aden was a 16-year-old who journeyed in 1950 to clerk for A. Besse & Co., on to distributing Shell petroleum products. He was Dhirubhai Ambani, dreaming of an oil refinery for India. Besides Brits were the French, Italians, Greeks, Jews and a few Chinese. The port refuelled ships routed from Europe to India, other parts of Asia and Australia.

Kaikobad Pudumjee, Jehangir’s second cousin, shares how the family was gifted Leo, the pet lion, from either Ethiopia or coastal Zanzibar to which they sailed a service. The cub was pampered in their Steamer Point compound. “Our Aden home huge enough for him to roam the first floor, its antique carved furniture was nicked by claw marks,” he remembers, laughing. Growing larger and louder, Leo’s sunset growls scared away evening shoppers. At the Governor’s request, he was shipped to the Victoria Gardens zoo in Bombay.

The leonine tale is charming family lore. A dramatic episode stirring the entire faith is of the Aden Atash (fire), of the holiest Adaran grade, brought to Bombay in November 1976. Cowasjee had erected the Aden agiary for Parsi migrants in 1883. Communism seizing Yemen a century after, they were determined to fly back the flame, which nurtured them on foreign shores. It was an act of courage and conviction. Pressure mounted for the move from the Indian Foreign Ministry and Indira Gandhi personally intervened. Attending a diplomatic conclave in Colombo, YB Chavan persuaded the Yemeni administration to release the Atash.

Venerated by an all-Parsi crew aboard Lhotse, Air India’s chartered Boeing 707, the sacred fire “rested” at Mahim’s Soonawala Agiary, before being convoy-escorted to Lonavla’s Adenwalla Agiary, where it still glows beautifully.

“This compilation studies the idea of industry going ahead of prosperity to be involved in every aspect of philanthropy,” says Bombaywalla’s archive keeper Kamna Anand. Categorising memorabilia that mostly came to light this year—postcards, letters, minutes of meetings for funded projects and plans of Aden’s “Parsee Enclosure”—she naturally finds more thorough documentation for successive generations.

Internationally respected as trusted bankers and ship chandlers, the family hosted George V in 1911, arriving for the Delhi Durbar to celebrate his coronation. Chairs from that function continue to be used in Adenwalla Baug, their ancestral mansion at Tardeo. Cowasjee’s son Hormusjee was an esteemed guest at the 1930 Bombay Central Station opening ceremony and, the year after, at the first Bombay Historical Congress in the University Council Hall. The 1927 Cowasjee Dinshaw Centenary Memorial Volume, by Framroze Ardeshir Dadrawala, holds biographical sketches of Aden’s Parsis led by the exceptional daring of Cowasjee Dinshaw.

Spending pleasant afternoons translating records from Gujarati to English, journalist Farrokh Jijina uncovered ample evidence of generous endowments. Gujarati documents refer to Cowasjee Dinshaw Darjina. Suggestive of a tailor, Darjina was the surname his grandfather, acquired in Bombay. Adenwalla got appended later. Both indicate the assignation of surnames based on occupation or native place. It was for Bombay society the Adenwalla suffix spelt cachet; in Aden resided many Adenwallas. “Cowasjee Dinshaw Adenwalla” signed a list of terms for the firm’s donation towards constructing the Anjuman Atash Behram, a major new fire temple at Dhobi Talao in the 1890s.

“Cowasjee Dinshaw is an inspiring example of what individuals achieve with foresight, ambition and ability,” says Jehangir Patel. “Similar archives will be an impetus to others to disseminate documents related to their families, neighbourhoods, cities or countries.”

“I Feel A Load Off My Shoulder”

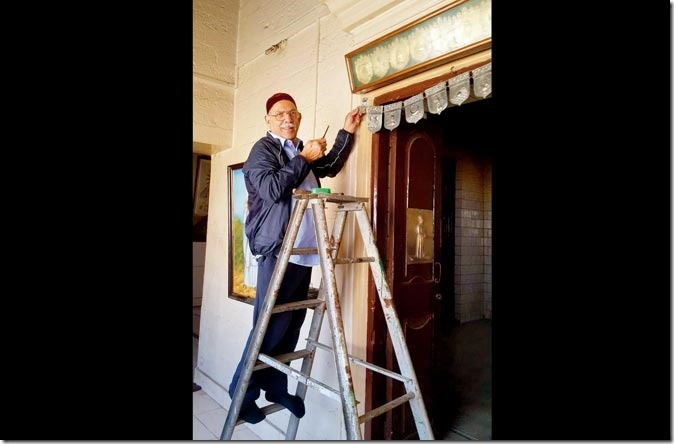

Maravala fixing the Aden Agiary’s toran at the doorway to the Lonavla fire temple’s sanctum sanctorum. Pic courtesy/Filly Maravala

Filly Maravala, the first Zoroastrian Mayor of London, in 1999, recently reunited the Aden Agiary’s silver toran with the Lonavla fire temple’s Aden Atash Padshah Saheb holy flame.

“I left Aden in 1967. After 15 years, I revisited our Agiary, looked after by a gentleman I know as Madan Uncle. He urged me to bring back to England several Agiary artefacts, for fear of these falling into wrong hands. Wary of the Customs, I took only this easily foldable silver toran.

Asked by a Yemeni Customs officer what the article was, I explained in fluent Arabic that it pertained to my religion. Unfolding the toran, I put on my cap and recited the Ashem Vohu prayer. He cleared me.

From 1982 till 2016, I had the toran in my house, carefully polishing it on auspicious occasions. An inner voice urged me to reunite it with the Aden Atash Padshah Saheb enthroned in Lonavla. I contacted Sarosh Dinshaw, a trustee of the Lonavla Agiary, promising I would personally fix it there. On December 24, 2016, I hung it on the door leading to the Atash Padshah Saheb. I feel a load off my shoulder. People may come and go, but our beloved chaandi nu toran will forever stay close to Aden’s Atash Padshah Saheb.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at mehermarfatia@gmail.com/www.meher marfatia.com