From to ‘Hind’ and ‘Hindostan’ to ‘Chashma’ and ‘Biryan’, the words you know and the language and history you don’t. Persian

“The best memory is that which forgets nothing, but injuries. Write kindness in marble and write injuries in the dust.”

This is not a quote without context. The India of today (2021, can you believe it!) often forgets its own history, and it is understandable to forget what hinders in the process of moving on. The seasons, clocks and life itself teaches us the art of moving on, but only if we are observant enough. Often, forgetting the ingredients of the dish can make the taste fade in due course. Such is the status of Persian language in India, we eat it, drink it, smoke it …… live it but are seemingly ignorant about it.

Article By Tauhid Khan | The Second Angle

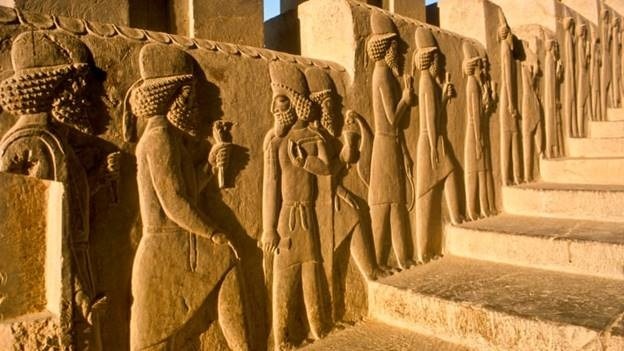

Credits: History.com

Persian or Farsi was brought to the Indian subcontinent in the 13th century by the Persian rulers of Central Asia. In fact, the word Hindu, connoting people living in a geographical region beyond River Indus, is of Persian origin.

The language was not only the lingua franca of the classes just like English in the India of today — but also the language of artistic literature and philosophy. So is the word Hindavi, which later evolved into Hindi, used for the language spoken by the people in large parts of this land. After being the major language almost throughout the medieval era of Indian history in communication and literature, the language was replaced by English in the late 19th century. And now it faces infamy or stupor.

All through the Islamic conquest of Persia in and around the mid-7th century, the Parsis took shelter in Gujarat and parts of western India to avoid religious persecution. And that is how Farsi made its way into India. Persian language, with pre-historic roots in southwestern Iran, is one of the oldest Indo-European languages. The Arabs captured Persia but were unsuccessful in imposing Arabic on the conquered.

The Persians were compelled to accept the Arabic script but did not surrender their language. Instead, Farsi turned into a prominent cultural language in most of the largest empires in Western Asia, Central Asia and South Asia. Newer literature, especially Farsi poetry, started developing as the part of the court traditions in the eastern empires.

Thus, Farsi became a vehicle of cultural conquest defying Arabic political hegemony. As a result, some of the classics of literature, such as Rumi’s Mathnawi, Firdausi’s Shah-Nama, Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat, Hafez’s Divan and Saadi Shirazi’s Gulistan, were written in Farsi in the medieval period. Farsi also became the vehicle of Sufi mysticism and theology, flouting all orthodox religious boundaries.

Credits: Mohamushkil.com

Its secular, liberal and strong cultural links helped Farsi survive political threats from Arabic and other languages. Even rulers of Turkish-Afghan origin in medieval India, including those of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal regime, accepted it as the language of the court and diplomatic discourse. In fact, they chose Farsi rather than their mother tongue Turkish, or Arabic.

Persian flourished in the Indian subcontinent, unlike in northern Africa where the conquered nations fell to the dominance of the Arabic language enforced upon them by the ruthless and powerful Arabs. Patronage of the language stimulated the flow of Persian texts and Persian speakers who were mainly soldiers, merchants, bureaucrats, scholars, poets, Sufi saints, artists and artisans to South Asia between the 11th and 18th centuries.

The decision to incorporate Farsi was in reality, a political move by the monarchs to get the better of the orthodox ulemas or Muslim theocrats who were mostly proponents of Arabic and Turkish. Irrespective of their ethnic, religious or geographical origin, these migrants from central and western Asia had skills in Farsi that would help them earn a livelihood in courts and bureaucracy.

Farsi reached its pinnacle in south Asia when Mughal emperor Akbar established it as the official or state language in 1582. Mind you, this was despite the fact that the Mughals were native speakers of Chagatai Turkish. Akbar used the language as a tool to knit together diverse religious and ethnic communities in his court as well as his burgeoning kingdom, culturally.

Not just Muslim aristocrats, but also scribes of upper-caste Hindu lineage — Brahmins, Kayasthas and Khatris — who served as clerks, secretaries and bureaucrats, learnt the language and got acculturated in Persian etiquette for social mobility. Ghazals, nazms and qawwalis (at Sufi shrines) in Farsi were wholeheartedly accepted as forms of literary and musical expression by the educated of all faiths and ethnicity.

Akbar and Jahangir commissioned Persian translations of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Dara Shikoh went a step further when he took up the task of translating the Upanishads into Persian, aided by veteran bureaucrat Chander Bhan. Persian romances, such as Laila Majnu and Yusuf Zuleika, were translated into many Indian languages.

The medieval Bahamani Sultanates and successor Deccan Sultanates and even the Hindu Vijayanagara kingdom had highly Persianised culture. The Sikh gurus as well as the Maratha ruler Shivaji were well-versed in Persian. The language had been used by the Bengal Sultanate as one of the court languages and in the chancery’s administration mainly in urban centres in Gaur, Pandua (today’s Malda), Satgaon (a port in Hooghly) and Sonargaon (near Dhaka), long before the Mughal period.

One of the principal patrons of Farsi in the early 15th century Bengal was Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah who established contact with the legendary Persian poet, Hafiz. Poet Alaol composed literature in the language and translated Persian classics into Bengali.

Royal patronage encouraged a section of non-Muslim elites in Bengal, especially the Bengali Hindu gentry and aristocracy, appropriate aspects of Persian culture, such as dress, social practices and literary taste. Rammohun Roy wrote treatises in Persian and started India’s first Persian newspaper Mirat-ul-Akhbar in 1823. The country’s first Persian printing press was also set up in Calcutta.

In the initial phase of the British administration, Persian was used as the language of the courts, correspondence and record-keeping. Governor-General Warren Hastings, well versed in the language, founded the Calcutta Madrasa where Persian, Arabic and Islamic Law were taught. The remnants of Persian judicial terms adalat, mujrim, munsif and peshkar are still used in courts across India.

The sharp decline of Persian began when English was made the language of governance through Lord Macaulay’s education policy in 1835. The emergence of vernacular languages, especially Urdu, ushered in further decay of Persian.

Credits: riaan.tv

Persian was, after all, a foreign language of the privileged and royal. Urdu first emerged as the common language of soldiers of mixed origin (Mughals, Rajputs, Pathans, Turks, Iranians, etc.) in the Mughal camp, and then became a language of the multitudes. Urdu took shape as a mixture of Persian, Arabic and Turkish words formed with the intermingling of invading Muslim armies and local Hindi-speaking Hindus.

It’s a Turkish word which means Army camp, hoard, etc. The most popular theory that many historians ascribe to is that Urdu evolved with multiple contacts from Persian and Turkish invaders, and thereafter developed during the reign of the Sultans of Delhi as well as the period of the Mughal empire. Urdu borrowed elements from Persian — idioms, styles, syntax, script — and mixed these with the local dialects, such as Poorvi and Brajbhasha.

Persian is a language that has challenged all borders and divisions. It’s an impartial language of poetry, philosophy and culture that has integrated political and partisan divisions for around a millennium now and shall keep its contribution to the languages of the subcontinent across multiple countries. Upholding its greatness is a fitting tribute to the legacy and impact it has had on India and its languages and will go a long way in understanding a real perspective about the combined past of our country and its neighbours.