A Parsee from Bombay who captured the imagination of an eight-year-old in Lancashire

By Michael Henderson / cricinfo.com

I first went to Old Trafford in 1967, the so-called Summer of Love. Lancashire were anything but a groovy side at the time – though the players looked pretty smart to my eight-year-old eyes – and it wasn’t until Jack Bond took over captaincy in 1968 that their cricket began to improve. That was Farokh Engineer‘s first year at the club, and it didn’t take him long to become my hero.

I first went to Old Trafford in 1967, the so-called Summer of Love. Lancashire were anything but a groovy side at the time – though the players looked pretty smart to my eight-year-old eyes – and it wasn’t until Jack Bond took over captaincy in 1968 that their cricket began to improve. That was Farokh Engineer‘s first year at the club, and it didn’t take him long to become my hero.

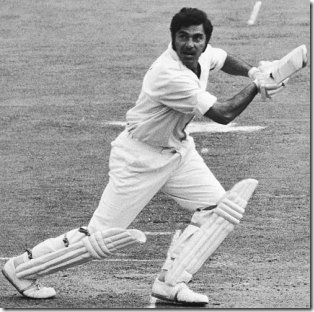

Engineer caught my attention that summer when he kept wicket for India on their tour. There was something exotic about the way he walked to the crease – it was a proper mincing walk – and his flourishes behind the stumps were also eye-catching. He was a show-off. And although he frequently got out when he appeared to be well set, there was something appealing about his batting, too. There was a hint of danger and, one should remember, in 1967, when Geoff Boycott was dropped by England for slow scoring after he made a double-century at Leeds, there was some pretty dull cricket.

With the walk, his engaging manner (a smile was never far away), that wide stance, and his eagerness to charge the bowlers, even the quick ones, it wasn’t difficult to warm to Engineer. He radiated an enthusiasm for cricket that one didn’t sense in the personalities of, say Ken Snellgrove and John Sullivan, admirable pros though they were. He was also Indian, a Parsee from Bombay, and that in itself was exotic. To this day I have always had a soft spot for Indian cricketers. Most of them, anyway.

Yet Engineer usually disappointed me. Whenever I saw him bat, the delight of anticipation soon turned to dust. Very often I wanted to go home when he was out, for the day had lost it bloom. As John Arlott noted, he had strokes that many heavier run-makers envied, but the long innings was beyond him. At prep school I picked up the papers every summer’s day to see how he had got on, and read with joy his maiden century for Lancashire, against Glamorgan. But the joy was compounded by another feeling – disappointment that I had not been there to see it.

Even when Clive Lloyd joined Lancashire in 1969 – and what feats he performed! – Engineer remained my favourite. Lancashire won the Sunday League that year, and again in 1970, when they also beat Sussex in the first of three successive Gillette Cup triumphs. Those really were the glory days. However much one-day cricket has changed in the last three decades, nothing and nobody will erase my memories of that Lancashire side, and Engineer’s part in it.

But the finest moment came not in one of those highly charged one-day games but in a championship match at Buxton in July 1971. Lancashire lost five early wickets to Derbyshire, and Alan Ward was bowling very fast, but Engineer kept pulling him into the bushes at midwicket. He reached the century I had longed to see him make, and had made 141 when he was finally out. That, at least as much as the famous Gillette Cup semi-final against Gloucestershire later that month, is the abiding memory of 1971.

In fact my bias towards Engineer went beyond the bounds of blood. He had been dropped from the Rest of the World side that played England in five unofficial Tests in 1970, so when he was at the crease at The Oval the following summer, knocking off the runs to help India win their first series in this country, I was almost as pleased as the Indians who led an elephant onto the field to celebrate.

There was something exotic about the way he walked to the crease – it was a proper mincing walk – and his flourishes behind the stumps were also eye-catching. He was a show-off

I can see now that he wasn’t the best wicketkeeper in the world, as we liked to think at Old Trafford. Alan Knott was; and Bob Taylor was magnificent. Nor was Engineer an outstanding batsman, though he was capable of the occasional bracing innings. Nor was he always a model of rectitude. He caught Mike Procter "on the bounce" in that famous Gillette semi, and was guilty of sharp practice on other occasions. At the time, though, any criticism of him was misplaced, for, in my eyes, he could do no wrong.

The end came quickly. At the conclusion of the 1976 season, two months after I had left school, and two weeks after Lancashire had lost a Gillette Cup final, he left the club. At the start of that season my other sporting hero, Francis Lee, the marvellous footballer, had also retired, so the summer of 1976 represented the end of childhood. It didn’t seem like that at the time. But when the 1977 season began there was a small hole in my life.

It isn’t always wise to meet your heroes, and I have only ever met Engineer twice, inconsequentially. No matter. That he played when he did, and in the manner he did, will always be good enough for me. Whenever I remember those days, I am nine again, and the world seems full of possibilities. Arlott was right. Engineer adorned the game more than players who ended their careers with better figures, and there’s a lot to be said for being a pleasure-giver.

Those you warm to in the early days, who mould your imagination, mean the most to you, whether they were great or not. So I remain faithful to the memory of "Rookie" and recall Fitzgerald’s valediction to Jay Gatsby: "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

This article was first published in the Wisden Cricketer

A great player!

A great player!

Dashing and always attacking – the best wicket keeper batsman that India produced. Was dropped after only two successive failures against the West Indies. A wonderful player who has left abiding memories. Irreplaceable.

Dashing and always attacking – the best wicket keeper batsman that India produced. Was dropped after only two successive failures against the West Indies. A wonderful player who has left abiding memories. Irreplaceable.