Past the Parsi hostel for women in Worli, through a narrow opening almost down a rabbit hole, lies the once-slum colony of Mayanagar. The birthplace of the Dalit Panthers in the 1970s has now been gentrified; there are apartments with lifts. A bright yellow crane at the entrance, however, indicates that work is still in progress.

Article by Mandira Nayar | The WEEK

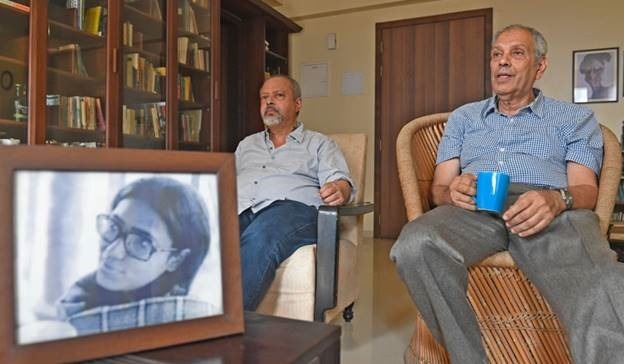

Kobad Ghandy | Photo by Amey Mansabdar

After spending a decade in several prisons, Kobad Ghandy—painted as the poster boy of the ultra-left movement in India—has returned to where it all began for him. Free now, he plods carefully with his walker. “Arthritis and sciatica are both jail products,” he says.

Old timers who recognise him stop to take pictures with an unmasked Ghandy. “I take things to build my immunity, then I do not worry that much,” he says.

Ghandy chats easily, reminiscing about the 1970s, when he walked in armed with a mat and printed material to awaken the people of Mayanagar into political consciousness. “I remember the first time I met him,” says Arul Francis—one of the young men Ghandy inspired—as he sits down with a milky cup of coffee. This is the first time the two are meeting in decades. Back then, Francis was among the many unemployed youth fired up by the ideas of B.R. Ambedkar, Karl Marx and Jyotirao Phule. “I still remember what was printed on the paper he brought when I first met him:

‘Bombay is the most densely populated city with 60 per cent slums. Why?’ We had no consciousness about social issues till then,” says Francis.

Despite his years in the field—even “declassing” to live in a dalit slum in Nagpur—Ghandy’s accent stubbornly remains. It is a constant reminder of privilege and the world he left behind. But it is not a barrier, and the camaraderie is real. “We would talk about everything in our lives,” says Rajesh Bhalerao, a dalit activist who was 17 when the Panthers came to be. An unemployed Bhalerao had received his lessons in political consciousness with Ghandy. “We were fighting for the fundamental rights that the Constitution guaranteed us,” he says. “We were raising issues of unemployment through the tools that democracy provided us, like protests. But there was also a blowback.”

In May 1972, having spent three months in a British jail for organising an anti-racism meeting (he had gone there to study chartered accountancy), Ghandy had returned to India, only to stumble upon Mayanagar. It was close to his parents’ flat in Worli, though it could have easily been another world. It is here, with its primitive drainage and lack of water, that Ghandy encountered caste.

The Dalit Panthers’ vibrant cultural revolt against rigid Hinduism, borrowing from the Black Panthers of America, was forcing questions of equality. Idealism, Marxism and communism offered the heady possibility of change.

“There used to be a car showroom across the road,” says Francis. “He asked us whether we would be able to buy a car even if we had the money or would we have to be content to just watch it from outside. It was our first lesson in class.”

It was a powerful lesson, one that changed Francis’s life. It also played a part in transforming the slum into its current state. “They stood on their own feet and managed to get the slum redeveloped,” Ghandy says with pride. “Across the road, the other side, the slum still remains. That is because they were not organised.”

There were many who drifted into the basti (colony)—a favourite place for college students to earn their social work stripes—but Ghandy was a regular. Mayanagar changed him. It became a lifelong commitment. He realised that his work there could become a lifelong commitment. A few years later, he took a further radical step; he and his wife, Anuradha, moved into the dalit basti in Indora, Nagpur. “It was not a sacrifice,” he says in his first in-depth interview after being released from jail in late 2019.

Ghandy’s prison days began in 2009, when he was arrested in Delhi and booked under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. “It is dehumanising, especially Tihar, where I spent the maximum time,” he says, matter-of-factly. “It is meant to break you. [Break] people like us, and people without money, resources or connections. And if you are somewhat sensitive, it is difficult to maintain your sanity.”

Then home minister P. Chidambaram had launched Operation Green Hunt, an all-out offensive against the “red corridor”, which stretched from Nepal to Andhra Pradesh and parts of Karnataka and Kerala. “Left-wing extremism (Naxalism) is the most violent movement in the country,” he had told top police officers in 2011.

This is the movement the police claimed Ghandy was an active part of.

“Kobad Ghandy was a central committee member of the Communist Party of India (Maoist). He was in charge of the international affairs wing of the banned outfit,” says K. Durga Prasad, who once headed Andhra Pradesh’s anti-Naxal force, the Greyhounds. He says that though he has no information on whether Ghandy actually participated in any Maoist operations against security forces directly, that in itself is no proof of his innocence. “He was extending logistical support to Maoists, arranging funds, organising meetings and was fully involved as a CC member,” he asserts.

In 2016, a Delhi court, and subsequently four other courts, found Ghandy innocent of any terror link. “The police had really no evidence,” says Ghandy’s lawyer Rebecca John. “We demolished the case, witness by witness, relying on inconsistencies and contradictions. It was one of the earlier cases under UAPA, but once the Delhi court ruled there was no evidence to connect him to a banned organisation, he was able to get relief in almost all his pending cases on similar charges across the country.”

Out now, Ghandy stays with his sister and has spent his time writing. He learnt to type in jail. His first book Fractured Freedom: A Prison Memoir, published by Roli Books, hits stores later this month.

Born to Nargis and Adi Ghandy, who were from “the typical Parsi/corporate background”, Ghandy’s commitment to the communist cause seemed highly peculiar. He had studied at the elite Doon School, with Sanjay Gandhi as his classmate, and hardly seemed the kind for revolution. “He was a shy, withdrawn fellow,” says Gautam Vohra, his classmate in Doon School. “One would have never imagined that he would get so involved with any issue, especially communism. He never paraded his views, he never made a big display. But you could see he had commitment.”

Also read

Ghandy is gentle, almost professorial, and charmingly idealistic even now. His conviction in communism apart, he has found support from friends and family, though they do not share his vision.

His life changed when he met Anuradha Shanbag, to whom the book is dedicated. There was love, marriage and shared ideology. Involved with the Progressive Youth Movement, which was inspired by the Naxal movement, Anu was a firebrand intellectual committed to the cause.

Her parents shared the same ideology. “There was very little choice if you came from my family,” says her brother Sunil Shanbag, who expressed his ideology in theatre. “I was in Rishi Valley [School], when I got a letter from her talking about why the nationalisation of banks was right. Anu was then only 14.” Over the years, Anuradha got more radicalised. “I remember she went to a camp of Bangladesh refugees in Madhya Pradesh, and she came back changed,” he says. There were intense discussions with her father over politics, even though they were both leftists, and Anuradha chose a different life. “Kobad came here often, and we soon realised that there was a relationship,” says Sunil.

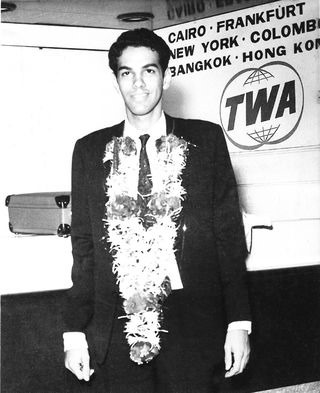

New horizons: Ghandy at the Mumbai airport on his way to London to study chartered accountancy in 1968

They married in 1977, when the Emergency was lifted. They were both involved in the civil liberties movement at the time and founded the Committee for the Protection of Democratic Rights in Maharashtra. A few years after the wedding, the couple moved to Indora and got actively involved with organisational activities. They deliberately kept away from family to avoid attachment. Anuradha cycled 15km daily to reach the college where she taught. They led a frugal existence. “It must have been difficult for my sister. It must have come at a personal cost,” says Sunil. “She was an avid letter writer, too, and while clearing my mother’s stuff after she died, I found her letters from her period in Indora. She must have realised that her parents were anxious.”

Except for a few short visits early on, they kept away from relatives. There are no photographs of the couple with their families after marriage. When her father died, Anu could not go home. It was just one of the extreme steps that the two took to keep focus.

They also decided to not have children. “In those days, in Andhra Pradesh,” writes Ghandy, “it was a norm that if a young married couple were both active revolutionaries, the male member would have a vasectomy to avoid children, which required additional attention and [would] distract from one’s activities. Anu and I, having decided to dedicate our time to the poor, followed this norm after marriage.”

In 1999, the couple returned to Mumbai; Anu had been asked to leave Nagpur University (where she taught) for her political activities. She had become a mass leader, and “her work with trade unions and women was increasingly coming under the scanner of the cops,” writes Ghandy.

She then went to Bastar for two years to work with the tribal women. On one of her trips to the forest, she contracted falciparum malaria, which led to an untimely death. “It was the worst day of my life,” says Ghandy.

The famous picture of Anuradha, smiling with thick, black frames, is from the morning of the wedding. “I had taken it with my camera,” says Sunil. “It was only after her death in 2008 that we found a few more that some friends had from an earlier period.”

The two most seen pictures of Ghandy—laughing on his wedding day and dazed on the day he was arrested—serve as a before and after poster. The years in between the two events have been captured in the new book. “Kobad’s story has fascinated me since I first heard about him,” says Priya Kapoor, editorial director at Roli Books. “We corresponded while he was in prison and I expressed interest in publishing his book whenever he was ready. Few live a life true to their convictions, especially when it leads to tremendous hardships. I hope his story is read widely; it deserves to be.”