A total absorption in her work coupled with frequent walks is Ratamai Peer’s mantra for sound health at 91

Article by

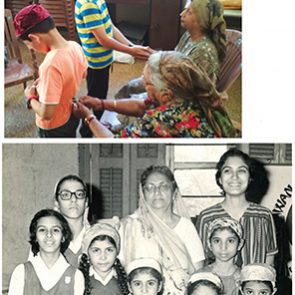

It is not uncommon to spot a group of children huddled around Ratamai Peer wherever she goes. Peer, aged 91, is known to generations of Parsis as a gifted and dedicated religious instructor. This year marks her 50th as a teacher of religion in Bombay. Nevertheless, she reveals few signs of slowing down.

The nonagenarian dons several hats. She is the leading light in Youths Own Union (YOU), a community organization, a dharmgyan (religious knowledge) teacher at leading Parsi schools and a tireless social worker. With the help of her daughter Tehmina, she teaches children the Avesta prayers, Parsi songs and Gujarati language basics. “Children are my therapy,” she proclaims in Gujarati, a language in which she is proficient. “There are times when I feel low because of an illness or other problems. But the minute I enter the classroom and greet my children, I am filled with unbridled energy and all my problems recede to the background.”

The nonagenarian dons several hats. She is the leading light in Youths Own Union (YOU), a community organization, a dharmgyan (religious knowledge) teacher at leading Parsi schools and a tireless social worker. With the help of her daughter Tehmina, she teaches children the Avesta prayers, Parsi songs and Gujarati language basics. “Children are my therapy,” she proclaims in Gujarati, a language in which she is proficient. “There are times when I feel low because of an illness or other problems. But the minute I enter the classroom and greet my children, I am filled with unbridled energy and all my problems recede to the background.”

Peer was born in 1926 in Navsari, one of six siblings to Dinamai and Ervad Dosabhoy Kanga. Priestly rigor and discipline governed their regimen. “Every day after breakfast, everyone at home was mandated to perform the daily prayers,” Peer noted. “If any child was found to have skipped praying in the morning, their lunch plates would be taken away and their share of food would go to the neighborhood dogs.”

She studied at the Tata Girls’ School in Navsari and then, at the young age of 16, joined its teaching staff. In 1950, she married one of her cousins, Ervad Peshotan Peer. “It was a 100% happy marriage,” she reminisces. “We had a lot of interests in common, reposed abiding trust in each other and never interfered in each other’s work.”

She studied at the Tata Girls’ School in Navsari and then, at the young age of 16, joined its teaching staff. In 1950, she married one of her cousins, Ervad Peshotan Peer. “It was a 100% happy marriage,” she reminisces. “We had a lot of interests in common, reposed abiding trust in each other and never interfered in each other’s work.”

In spite of being married, she was determined to continue with her teaching career. Luckily, she found robust support within her own family. “You have to choose between being dedicated to the kitchen and having a career,” Ratamai’s father counseled and her husband wholeheartedly supported her decision to pursue the latter course.

Ratamai found new avenues for teaching after relocating with her family to Bombay. One day in 1968, she took her children to a religious class at Bharda New High School organized by YOU. When two of the instructors failed to turn up, she decided to deliver a lecture herself. Taking a cue from the weather outside, she spoke about rain. “I spoke of the rains as God’s cleansing agent which washes away all the dirt from the trees and the open surfaces that man cannot clean,” she recounted. Her impromptu lecture impressed the trustees and other attendees to such a degree that she was immediately appointed as a teacher of religion at the school.

This appointment, which she labels as the turning point in her career, was the springboard for her engagements with other schools. Subsequently, she took on teaching assignments in Bai B. S. Bengallee Girls High School, Bai Avabai Framji Petit Girls High School, The J. B. Vachha High School for Parsi Girls, Sir J. J. Fort Boys’ and Girls’ High School, Bai M. N. Gamadia Girls High School and Cusrow Baug. Presently, she conducts religious classes at Gamadia Colony, Gamadia School, J. B. Vachha School, Cusrow Baug and lectures at evening programs conducted by YOU. When asked about how many students have been under her tutelage over the past several decades, Peer found it hard to estimate that figure. Many of her former students are now grandparents and their grandchildren now file into her classes. Consequently, she remarks, “I probably hold the record for attending the most Parsi weddings and navjotes in the community.”

The instructor is renowned for her Gujarati script teaching technique. “I can easily teach a child the Gujarati script within 20 minutes, if the child is familiar with Hindi,” she declares. Her passion for promoting Gujarati language skills is exemplified by the numerous Gujarati writing competitions she organizes for children. But her students are not confined to children — adults eager to learn the Gujarati script also approach her. One such student, Kainaz Najmi, is a mother of two and a chartered accountant by profession. While Ratamai trains Najmi’s children in Avesta prayers, Najmi learns the Gujarati script from her. Najmi, who considers the senior citizen to be “a motivating and confident teacher,” now has a good grasp of the script. “Her dedication to encourage children to imbibe the basic tenets of our religion is commendable,” she says appreciatively of Ratamai.

“The focus of our classes,” the instructor’s daughter, Tehmina, explains, “is to incentivize children to continue praying even after their navjote ceremony. We attempt to do so by inculcating the importance of prayers in them and by enabling them to read the Gujarati script independently.”

The lady recounts teaching a class full of 60 children in the early days of her teaching career. Now, the number has diminished considerably. She has frequently walked into near empty classes. Undeterred by the falling numbers of students, she says, “I am willing to teach even if there is only one student in my classroom. Even if this single student learns from me and teaches a few others, my purpose has been achieved.”

“The focus of our classes,” the instructor’s daughter, Tehmina, explains, “is to incentivize children to continue praying even after their navjote ceremony. We attempt to do so by inculcating the importance of prayers in them and by enabling them to read the Gujarati script independently.”

The lady recounts teaching a class full of 60 children in the early days of her teaching career. Now, the number has diminished considerably. She has frequently walked into near empty classes. Undeterred by the falling numbers of students, she says, “I am willing to teach even if there is only one student in my classroom. Even if this single student learns from me and teaches a few others, my purpose has been achieved.”

Compensation has never been the driving force behind Ratamai’s work. In fact, much of it is voluntary. “I don’t rue the fact that I have no provident fund savings. When I see my students praying as mobeds in agiaries, I think to myself, there lies my provident fund.” Recently, while sitting by the shore in Udvada, she was approached by a number of her former students who offered gratitude for her instruction. Some credited her training for their ability to become priests at the Iranshah.

The year 2013 proved to be significant for the veteran instructor. In recognition of her selfless service to the community, she received the “Unsung Heroes Award” and a cash prize of one lakh rupees at the 10th World Zoroastrian Congress in Bombay.

Ratamai continues to follow an enviable schedule for someone her age. With absolutely no reliance on mobile phones or computers, she commits her whole schedule to memory. “The secret to my good health,” she says, “lies in completely immersing myself in my work and my frequent walks along Marine Drive.” Aside from teaching, she persists in her social work activities, helping the poor inside and outside the community by coordinating with various trusts for the release of funds, food and educational and medical aid.

When asked about her hope and vision for the community, she remarks, “I wish that more Parsis take an active interest in their religion and culture. I also hope that Parsi parents encourage their children to learn more about our wonderful religion. I really pray that members of our community live peacefully, resolve their disputes amicably and do not take their fights to the Press.

“I have led an extremely satisfying and happy life without any regrets,” she concludes. “If I had the chance of being reborn, I would love to be reborn in this community and continue doing the teaching work I have done in this life.”