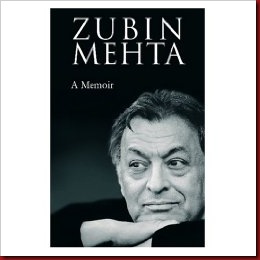

Zubin Mehta, one of the greatest conductors of western classical music of all times has come out with his autobiography titled The Scores of My Life, published by Roli books.

Zubin Mehta, one of the greatest conductors of western classical music of all times has come out with his autobiography titled The Scores of My Life, published by Roli books.

In the book, he writes about India, his younger days, his family and friends, his musical journey, his love for hot chillies and more. Here are a few excerpts from his autobiography.

From Chapter 1:

My early years in India (about not giving up the Indian passport)

I attended a school run by Spanish Jesuits in Bombay. This might seem unusual but there was a simple reason behind it. Schools run by Jesuits were considered the best in India. Moreover the medium of education was English, which was something that my parents attached great importance to. Above all it offered my brother and me an experience, which was certainly formative for our lives.

St Mary’s High School accepted male students from a very wide range of backgrounds, particularly in respect of religion. This was in a way a unique situation, but simultaneously symptomatic of the matter of course way in which one deals with religion in India – something which unfortunately does not apply to the ancient conflict between Hindus and Muslims. The approximately forty students in my class belonged to six or seven different religions.

There were Hindus and Muslims, Parsis and Sikhs, Jews and Christians among us and we coexisted in perfect harmony. Nobody tried to convert us to Catholicism. We studied the gospels as literature and that was all.

I believe that going to this school indoctrinated in me a high esteem for the great diversity among people and taught me very early to respect differences. I learnt quite naturally that people from completely different circumstances could get along with each other as long as they accepted that being different did not automatically imply being a foreigner, which leads all too easily to mistrust.

It seems to me that a facet of my later life, which saw me travelling all over the world and coming in contact with the most diverse people, had its roots here. On the other hand I consider myself an Indian even now. This is also why I never gave up my Indian passport. Now as ever I feel a sense of belonging to the country I come from – India.

Where he talks about his father’s influence

I grew up in these surroundings with my father practicing music in the living room, and with the musical scores scattered all around the house. I liked looking at them even though I could barely read them. My father also had something marvellous, a record player on which we could listen to music endlessly.

Not surprisingly, this gramophone was a real monstrosity. The records in those days, that is, in 1940s, had a ridiculously short playing time so that one had to put on a new record after barely five minutes of playing a symphony or a quartet. The vinyl records with their hair-thin grooves, on which one could record really long works, did not exist back then, not to mention the CDs. Some symphonies were pressed on four or five of such records. As a result one was compelled to constantly run to the record player and to put on another one of these breakable and easily scratchable black discs extremely carefully if one wanted to hear the symphony in its entirety.

My father’s record collection was quite impressive by the standards of his time. This enabled me to listen to the most magnificent music all the time. Since I could not read at all in the beginning I distinguished between the pieces on the basis of the different coloured labels on the records. From early on I heard symphonies and became familiar with Beethoven and Johannes Brahms. I also heard a bit of Gustav Mahler. Later I would often miss my favourite sport, cricket to attend a rehearsal of my father’s string quartet.

My father founded the Bombay Symphony Orchestra in 1935, and also the Bombay String Quartet, and they also practiced at our home. In fact I was wrapped up in and surrounded by music. Music was my daily pleasure. The records, the practice sessions of the quartet and my father playing music, all this meant no more and no less to me than a very early access to paradise. I entered this musical pleasure garden as a very young person and so far nothing and no one has managed to drive me away from it.

From Chapter Two:

My Student Years In Vienna (where he talks about his early days as a student of Music)

A musical experience barely a month after I arrived in Vienna is still vivid in my memory. I was passing by the Musikverein auditorium when, following a sudden whim I slipped in through the rear entrance. I heard music; it was the 4th Symphony of Tchaikovsky. And again, I was familiar with this piece from one of my father?s records of the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky. However, what I heard through the doors sounded completely different. Once again I experienced a sense of wonder at this pure and direct form of music. I ran a little further along the corridor and came to a door with a small, round viewing window, through which I could look into the auditorium. Herbert von Karajan stood there. I had never seen him in person before and only recognized him from pictures, but it was undoubtedly him. I crept in through the door as quietly as I could, slipped into a seat and listened in amazement. Nobody discovered me there or threw me out. I was simply there and stayed there. This is how I experienced Karajan for the first time. Once again I had the overwhelming feeling that my ears were straining to open up, so that I could listen to this real music in the right way.

In this way I came to know music which I had imagined I already knew. I cannot express it in any other way. Everything that I had thought I was already familiar with became clear to me now for the first time. This new listening was often far removed from what I was used to. Time and again I made new discoveries. I felt like Columbus on a musical expedition. I set foot on a territory, which was completely new to me, though I already knew its outlines. It was an enriching and wonderful time during which the foundation for everything that I later achieved was laid.

I had listened to a lot of music in Bombay but a certain bias in the selection of music was naturally rendered unavoidable through my father?s personal preferences. Hence I discovered Mozart for example only in Vienna, and thankfully in the right way.

From Israel ? Another Love Story

(Where he talks about his relationship with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra)

The Israel Philharmonic is like family to me. Apart from a few exceptions I have chosen and appointed the musicians myself from among the candidates shortlisted by a special committee. I am familiar with every little characteristic of this orchestra, just as they know every single gesture of mine. Conducting is to a large extent communicating. It helps when there is a good level of understanding between the two parties, that is, when they understand each other without anything being said, in other words before we begin to play or conduct. When the orchestra and the conductor communicate so well as a team, as in the case of the Israel Philharmonic and me, then it is always possible to reach a true musical consensus. In this case it is not about striving for the lowest common denominator, but rather aiming at the maximum attainable.

It is easier for me to reach this level of communication with the Israel Philharmonic as compared to other orchestras even though it is not exiled Poles or musicians from Vienna and Hungary who anymore call the tune. Most of the members of the orchestra now are from Russia and I, unfortunately, cannot communicate with them. But even if our verbal communication does not work so well we understand each other perfectly at a musical level.

During my initial years in Israel I also knew many of the musicians personally. We met outside the concert halls and they even invited me to their homes too. I think that for some of them I played a role that lay somewhere between those of a confessor, psychologist and career counsellor.

It is a highly interesting phenomenon for me, and very stimulating for my work, that musicians from different parts of the world understand music in completely different ways. I have repeatedly emphasized the strong influence of Vienna on me musically. I grew up there in a very particular tradition and internalized the entire cosmos of this musical tradition from Haydn to Webern. Perhaps I even went so far as to sacrifice precision in favour of a warmer sound. Similarly in Israel I tried to convey my idea of sound to the musicians, particularly in the case of music from the nineteenth century. This is even possible with the Viennese waltzes, which are more difficult to play than one generally imagines. I practice a Strauss waltz with the Israel Philharmonic again and again. This is obviously not the genuine musical language of these musicians but it is important for me to make them understand even such music. I try to explain the right tone and style of this music, for example, the fact that the many accompanying figures in a waltz do not have to be played exactly as printed. On the printed page certain rhythms must be played in a sloppy but organized manner something that is very difficult to explain outside Austria. Even German orchestras do not always know exactly how this organized sloppiness works. I even have it written in the parts for the Israel Philharmonic. I enjoy such exercises. They bring some freshness into the orchestra. Besides they are also fun. And then, when the whole auditorium reverberates with delight, all of us feel rewarded too. But I have to admit that waltzes are perhaps still somewhat unusual in Israel.

From The Move to Munich

(Where he talks about his years with Bavarian State Opera)

I was already familiar with the musical landscape in Munich and was happy that I would finally be leading an opera house. In the meantime I had gathered a lot of experience in the field of opera. However I had never really been a part of the usual business of repertoire performances as was traditional in Munich. Until I took up my job at the Bavarian State Opera I had essentially conducted more concerts than operas. All that changed with my appointment as ?Bavarian general music director? in 1998. I soon grew fond of the orchestra.

The choir was wonderful, the acoustics magnificent, and all of us worked together smoothly from the very beginning. Sir Peter Jonas took care of the administrative matters, all dealings with the ministry of culture and the search for sponsors. He was a wonderful mediator between art, politics and business and he knew how to get the Bavarian authorities and audience to commit to the new times. He had had gained immense experience of such things during his stint in Chicago and London.

Munich was also my first permanent engagement in Germany. My first repertoire performance gave me quite a few grey hair. I was suddenly expected to conduct an opera with just one rehearsal. Although I was comfortable in the field of operas by that time, it was nonetheless a difficult and challenging project. After all I had to learn something new again in my early sixties! The repertoire began with La Traviata. It went off more or less well but the next performance of Figaro did not turn out particularly well. One always needs more rehearsals for Mozart. The casting of the singers had not changed since the premi re. They made a good team and they could rely on each other. But then I arrived and my way of doing things was different from what they were accustomed to. In the very first performance I felt that there was something missing, that I lacked the experience of this long-standing team. It is even more difficult to suddenly step into a repertoire set than to start a new production where one is involved from the very beginning and grows with each performance.

In any case the orchestra in Munich was so experienced in matters of musical flexibility that the musicians were extremely helpful to a quasi novice conducting his first repertoire Mozart performance. Obviously in these early days they had not known me long enough to know what I always meant. Despite all the enthusiasm that an orchestra and a conductor might spontaneously feel for each other it takes a certain amount of time for a relationship to develop between them in which each little gesture is understood perfectly so that a connection can be established even blindly.

By the end of my time in Munich we had rehearsed and played so often together that we could even render Die Meistersinger without any rehearsals at all ? and it would be excellent. I conducted the ?old? Ring during my first season in Munich, which was replaced by a new production in 2002. My admiration for the orchestra grew even more on that occasion. I learnt a lot from the musicians and from their understanding of the correct style, and that too with Wagner.

From Chapter 5:

Nancy – A love story (about his children – two children born out of marriage)

At this place I want to say something fundamental about my personal life, something that I consider worth sharing. Most of all I would like to talk about the two children from my first marriage, Zarina and Mervon, who have already given me grandchildren.

My daughter lives in Canada. Both my children are workaholics in the true Mehta tradition. Zarina works in the field of nursing. She is a nurse’s aide and looks after sick people in a completely self-sacrificing way. She has two children, Daniel and Shenaya.

My son is the vice president of Programming at the Centre for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia, the Kimmel Centre. Earlier he was an actor, a good one I thought. After years of appearing on stages in New York- off-Broadway the Canadian Shakespeare Festival at Stratford in Ontario, and various successful freelance opportunities. He accepted a post in management at the Ravinia Festival in Chicago at the invitation of my brother before moving to Philadelphia with his wife Kerry. They now have our youngest grandchild Zed, who was born in 2003.

Despite the innumerable commitments that make my life so tumultuous I feel very closely connected to my children. In this respect again I have to compliment my wife Nancy. She accepted my children from my first marriage in such a way that she was always there for them whenever they needed her.

Finally I also want to speak about my two other children born out of marriage. There has been enough gossip on this topic. Enough has been said on conditions of anonymity, quoting supposedly reliable sources. My daughter, Alexandra, who lives in Los Angeles, was born out of a relationship that I had between my two marriages.

Alexandra was born in 1967 and already has three children – Alec, Kevin and Emma. I see them all whenever I am in Los Angeles and I am happy that Alexandra and Zarina also have a wonderful relationship. Nancy has taken care of Alexandra, even from a distance, with sympathy and understanding. I am so happy that they share a good relationship.

However, I deeply offended my wife and hurt her unendingly when I had another son in Israel eighteen years ago. I know that I inflicted a lot of pain on Nancy on that occasion. I can never thank her enough for bearing this pain and not leaving me, hurt and humiliated. It must certainly have been dreadful for her to find out first from me and then from newspapers that a son was born of a brief affair. The fact that she did not leave me helped me a lot in dealing with my mistake and the difficulties that followed.

Ori, my son, grew up with a wonderful family, the Zislings, in a kibbutz in the north of Israel. In the beginning he only spoke Hebrew, a language that I have not learnt in spite of working in Israel for so many years. Now, however, he speaks very good English and we can now talk to each other perfectly normally. He will soon be starting his career with the army.

From Chapter 7:

Friends – in music and musical encounters (About his fallout with Henry Kissinger)

Often so-called great events take place where a concert can create a wonderful setting for the business at hand. There can obviously be different opinions about whether this constitutes a misuse of music. In any case it is a part of public life.

The twenty-fifth anniversary of the United Nations was being celebrated in 1970. The festival programme included a concert with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which I was supposed to conduct at the UN headquarters. It was a very honourable responsibility. The heads of state of many nations were going to be present and Beethoven’s 9th Symphony with Schiller’s verses was supposed to create the right mood.

The premi re of Penderecki’s Cosmogony had been planned along with that. Obviously we had to rehearse intensively. Beethoven’s gigantic work had to be rehearsed carefully at the venue itself before the concert. The Penderecki premi re obviously also required really thorough work.

My problem with this jubilee concert was that the General Assembly was earmarked for Richard Nixon’s speech to the delegates during my rehearsal time. As luck would have it there was a festive dinner for the president before the anniversary in Los Angeles. Nancy and I were there, and were seated at President Nixon’s table. When he brought up the topic of the concert at the UN I grabbed the opportunity without further ado and told him about my problems with the rehearsals. I emphasized the importance of rehearsals and said that it was absolutely necessary to rehearse in the auditorium not only on account of the Penderecki premi re, but also because the acoustics of the General Assembly, which are not particularly good.

I think I made my point quite clear. Nixon sent for his the then security adviser Henry Kissinger and told him to reschedule the speech. It was not exactly Kissinger’s job to organize the allotment of auditoriums in the UN headquarters. However what else could he do, now that he had received instructions from his chief executive. Kissinger was more than furious and when at the end of the evening we met again in the lift he snarled at me with the retort, ‘I get you for this’.

I did not feel guilty at all. On the contrary I thought it was nice of Nixon to take an interest in my rehearsal. However, there was hell to pay. Nixon’s address was actually postponed to another day and I could rehearse to my heart’s content. In his anger over my somewhat cheeky intervention Kissinger had come up with a drastic solution. Instead of regaling themselves with Beethoven and with Penderecki, the heads of state all made their way to Washington and not one attended my concert. Indira Gandhi wrote to me later that she would have loved to listen to Beethoven, her favourite, but alas could not refuse the Washington invitation.

It still remains to be said that I befriended Kissinger in later years and every now and then we still have a laugh about this story. So much about the philosophy that music provides for politicians to get together in peace.