Zoroastrian family’s business empire stands out for its philanthropic practices

Ratan Tata speaks during an interview with Nikkei in Tokyo in 2017. (Photo by Keiichiro Sato)

SATOSHI IWAKI, Nikkei staff writerSeptember 1, 2024 10:12 JST

NEW DELHI — I recently had the opportunity of being in touch with Indian business tycoon Ratan Tata again after a 10 year gap. He was able to recall our interactions back in 2013.

It was a polite and thoughtful correspondence, though I am not in a position to reveal more of its contents.

Tata, the chairman emeritus of the leading Indian conglomerate Tata Group, is a prominent player in the corporate world. Although he has largely retreated from the vanguard of business, he is still respected as a consummate executive at home and abroad.

His life story was followed closely in Japan as his biography ran in Nikkei’s My Personal History column throughout July 2014.

In 2013, I visited Mumbai to ask Tata to share his personal history with our readers — and to share a meal with him. His e-mail suggested that our time together was memorable.

India has several powerful business conglomerates, including the Adani Group led by Gautam Adani and Reliance Industries headed by Mukesh Ambani. Adani has an ambitious plan to invest more than $100 billion by 2032, and Ambani’s recent mega-wedding (reportedly costing about $600 million) rippled across global headlines.

But Tata Group’s image is unique among its peers. The biggest shareholder, Tata Sons, is both the holding company of the group and a philanthropic organization founded by the Tata family. Huge dividends from Tata Sons’ earnings often trickle down into local communities in the form of support for rural villages, education, medicine, culture and more.

Such a foundation appears to be constitutional to the Tata family’s religious background. The family is Zoroastrian and members of a religious-ethnic community in India called the Parsi. Zoroastrianism doesn’t believe in idolatry, calls for the worship of a sacred fire that symbolizes its God, and forbids cremation, burial and water burial.

Groups of Zoroastrians fled from Persia (modern-day Iran) to India around the 10th century and began to be assimilated into the local community. The ruler, or maharaja, of India at the time is said to have sent the migrants a vessel full of milk, signifying that his country was already full of people and had no more room for newcomers. As Zoroastrians tell it, a priest added sugar to the milk without it spilling, pledging that they would blend into the community, sweetening the culture “like sugar in milk.”

In keeping with this story, Tata once said that he believes his company can thrive by contributing to the development of entire societies in the long term, without pursuing short-term profit.

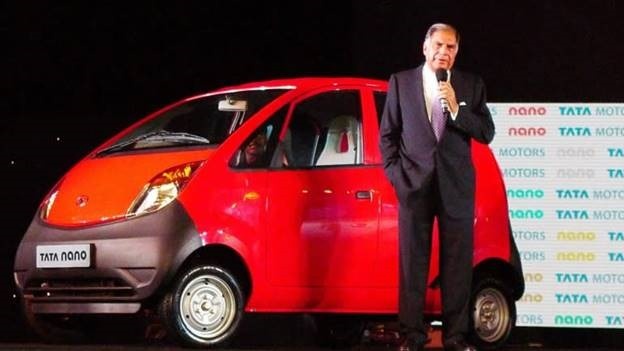

Ratan Tata speaks during the launch of the Nano micro-vehicle, which earned the title of the world’s cheapest car, in Mumbai in March 2009. (Photo by Nikkei)

His beliefs have already borne fruit in the form of the Tata Nano, a micro-vehicle released in 2009 as the world’s cheapest car with a price tag of 100,000 rupees ($2,200 at the exchange rate at the time). A well-known anecdote prior to the development of the Nano is that Tata may have first thought of producing an affordable vehicle for economically challenged people when he saw an entire family thrown onto the road when their motorcycle skidded in the rain; in India, it not uncommon to see a family of four riding together on a small motorcycle.

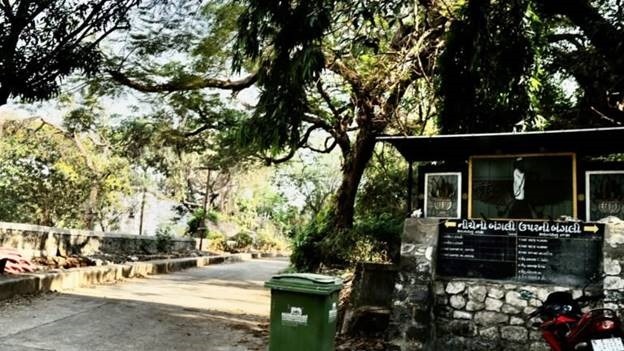

During a recent trip to Mumbai, I went to a wooded, upscale residential area that also happened to be home to a tower of silence (or dakhma) — a raised structure built by Zoroastrians for “sky burial.” Dead bodies are placed inside the tower so that vultures and other birds of prey can consume the flesh, thus taking the deceased up into the sky.

Only practitioners of the Zoroastrian faith are allowed to come close to the structure, but I was fortunate enough to be approached by the manager of a nearby building used for funeral gatherings who shared an interesting fact with me.

“Bodies remain left for a longer period of time these days because there are fewer birds,” he said, also mentioning some complaints from residents in the neighborhood about foul smells and the occasional macabre site.

The man presumed that the number of vultures and other birds of prey have decreased due in part to better veterinary care for cattle and therefore fewer of their carcasses to provide a meal. My own research also found that the birds ingesting environmental contaminants plays a major factor in the shrinking of their numbers.

For Zoroastrians, the body from which a soul has departed is considered impure and unclean. Thus, they cannot use fire for cremation due to its sacred nature. Burial under the earth is also banned because they believe it pollutes the earth.

Cremation by means of electricity, which uses no fire, is reportedly on the rise these days, but Zoroastrians are split over whether the practice is acceptable.

A tower of silence, or dakhma, stands in a wooded neighborhood in Mumbai. (Photo by Satoshi Iwaki)

So, why do Zoroastrians attach so much importance to sky burial?

In their own words, not only do they yearn for the roof of heaven but they also believe that they can celebrate their life by letting their flesh give sustenance to the birds. They are thankful for life until the very end, and this ethos leads them to want to leave legacies of contribution to society when they are gone.

The business practices of Parsi businesspeople are thus often different from their Indian counterparts who sometimes prioritize profit above all else. In my opinion this is why people take notice whenever Tata Group makes a move, asking, “What do they intend to do?” or, “What prompted them to embark on this new business venture?”

In my first meeting with Tata, he said that it is important to attach a great value to India’s large population of low-income people, rather than ignoring them. For him, it is a key element for corporate growth in the country.

As India prospers, Tata’s practices hold up a mirror to other businesses in the country, forcing them to consider whether they will continue to pay exclusive attention to the growing middle-class, rather than helping impoverished people.

My first contact with Tata in more than a decade reminded me of the mindset he explained to me all those years ago. Today, I firmly believe that companies and investors foraying into India should follow Tata’s principles and leave the world a better place than they found it.