He grew the Tata group into a world-beater. Now, with the Tata trusts, he wants nothing less than to change the world

By Prince Mathews Thomas | Forbes India

One does not attain freedom from the bondage of Karma

by merely abstaining from work.

No one attains perfection merely by giving up work

Because no one can remain actionless even for a moment.

Everyone is driven to action, helplessly indeed,

by the Gunas of nature

The deluded ones, who restrain their organs of action

but mentally dwell upon the sense of enjoyment,

are called hypocrites

The one who controls the senses by the mind and intellect

and engages the organs of action to Nishkam Karma-yoga

is superior, O Arjuna

Perform your obligatory duty,

because action is indeed better than inaction.

Even the maintenance of your body

would not be possible by inaction

Shri Krishna to Arjuna in the Bhagwad Gita

Dwell for a moment on these passages and the idea of Nishkam Karma-yoga. This epic conversation precedes the battle at Kurukshetra before Arjuna goes to face his cousins from Hastinapur and Shri Krishna wants Arjuna to be a Nishkam Karma-yogi.

Every action, or karma, Krishna tells Arjuna, has gunas or qualities. The noblest, he says, is Nishkam Karma—action without expectations. This, Krishna tells Arjuna, will calm the mind, allow him to pursue personal excellence, and is intended for the greater common good. As opposed to this, Krishna tells Arjuna, there is Sakam Karma, where all action is guided by aggression and the only outcome is personal success. The latter, he tells Arjuna, is undesirable because it eventually leads to conflict.

If you were to extrapolate these arguments into contemporary business, what you have on the one hand are men like Ratan Tata who’ve chosen the first path—that of Nishkam Karma—after what seems like a lifetime in the hard-nosed world of business. Then there are others, whose stories of hubris we’ve documented in recent issues of Forbes India who remain focussed on Sakam Karma, which, as Krishna argues, is destructive in the long run.

That is why understanding Ratan Tata and his motivation is important because what it provides are lessons in doing the right things in pragmatic ways.

What will Ratan Tata do when he turns 75 this year? We tried to address the question in December last year. The seasoned Jehangir Pocha, co-founder of INX News, described meticulously why Ratan Tata will pass the baton he now holds to Cyrus Mistry, as opposed to his half-brother Noel Tata, whom many had assumed would be the natural choice.

MORE FOR LESS The Systematic Rice Intensifi cation project is one of the most successful programmes funded by the trusts. It uses 30 percent less water, but increased yields by 40 percent. Bihar has now adopted this as an official programme

Pocha had then pointed out, presciently, “….if Ratan Tata resisted the urge to try and preserve his life’s work by handpicking his own successor, it is because he is believing and sincere in his desire to do—and be seen to do—the right and professional thing,” he wrote. It was easy then for many of us to imagine Ratan Tata would settle into an obscure life. We were wrong.

The first indication of that came in his acceptance speech for a Lifetime Achievement Award instituted by the Rockefeller Foundation when he said his life’s work isn’t done yet. And that he hasn’t been able to touch as many people at the bottom of the pyramid as he’d hoped he could by building affordable products. “We haven’t been successful or innovative enough” he said of his stint at the helm of the Tata group in an interview to Bloomberg.

This, in spite of the fact, that in 2010 alone, the Tata trusts disbursed Rs 500 crore ($80 million at current exchange rates) to various causes and institutions. In dollar terms, this number would have been higher if the rupee hadn’t devalued as much since then. The Rockefeller Foundation, one of the most generous in the world now, disburses $180 million each year. Experts say the Tata trusts are easily among the 10 most generous in the world. But their story remains an untold one.

Because no one can remain

actionless even for a moment.

Everyone is driven to action,

helplessly indeed, by the Gunas of nature

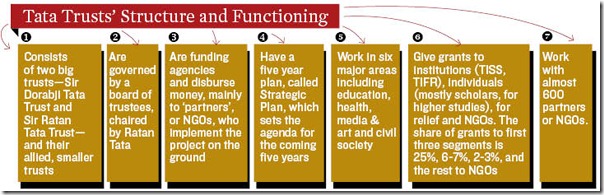

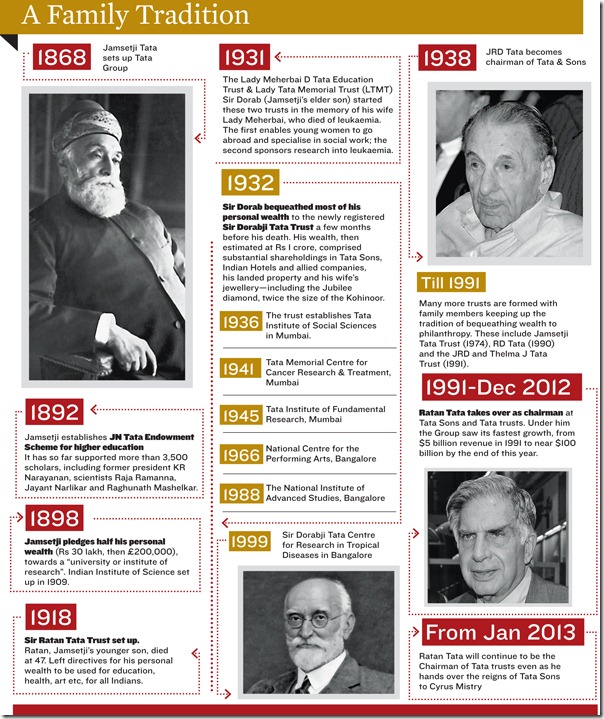

Until now, Ratan Tata has played a dual role as chairman of the Tata group and chairman of the Tata trusts. The trusts are a conglomeration of two big and many smaller units, the first of which was named after Tata’s grandfather Sir Ratan Tata. Before he died in 1918, he drafted a will that donated all of his personal wealth towards philanthropy. Since then, the family has donated their wealth in the company to existing trusts or created new ones.

When Tata was anointed chairman of Tata Sons in 1991, he was assigned charge of the Tata trusts as well, a traditional family responsibility. But in December this year, when he turns 75, Ratan Tata intends to break tradition. While he will step down from his responsibilities at the group, he will continue as chairman of the Tata trusts.

Nachiket Mor, former chairman of the ICICI Foundation for inclusive growth and now the man behind several innovations in rural finance and healthcare, says, “This is a big moment for Indian philanthropy. He has the ability to bring together and galvanise corporate leaders across the world. The impact will be similar to that when Microsoft founder Bill Gates retired from the company and channelled all his focus on the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.”

AN Singh, managing trustee, Sir Dorabji Tata Trust (SDTT), seconds the view. “There will be radical review of things.”

For many years now, Ratan Tata has been part of a circle of people with philanthropy on top of their minds. This includes Peggy Dulany, founder of Synergos, a non-profit organisation. Dulany is David Rockefeller’s daughter, the legendary American industrialist who set up the Rockefeller Foundation. In the past, Tata has been on the board of the Ford Foundation as well. His learnings from these experiences have been instrumental in shaping his thoughts over the years.

That he wanted to break from tradition is now obvious with the benefit of hindsight. As early as in 2005, in an interview to Synergos, Ratan Tata had said “Philanthropic institutions in India still believe they’re charitable and, therefore, must operate on shoe string budgets, that creating an organisation is almost a luxury. This needs to change—they have to recognise that a non-profit has as much responsibility for being professionally run as a corporate body.” But he also conceded it is a challenge as well because available data suggests there are more than three million registered non-governmental

organisations (NGO), of which at least one-third are active at any given time.

“Unfortunately, in India it is difficult to find partners who have the scale and capability to handle more than Rs 5 crore annually in grants,” says SDTT’s Singh. That is why Ratan Tata insisted the trusts start with training some of their partners to build scale. Tata has also argued the trusts ought to work globally as well. “As a group, we are a global entity. So why should the trusts be driven by geography? Surely, we can expand the mandate of the trusts,” says RK Krishna Kumar, a close associate of Ratan Tata, a director on the board of Tata Sons and a trustee as well. Like Ratan Tata, he will continue with his work at the trusts after his tenure at the group ends. “In Africa, we can collaborate and have aligned programmes with organisations like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation or the Ford Foundation, but without compromising on each other’s sovereignty,” he says.

Ratan Tata’s insistence to break away from tradition prompted the board of trustees to challenge how they function currently. For instance, investing in social enterprises. When the microfinance business in India, led by Vikram Akula’s SKS, went belly up, it compelled a pause until complete clarity emerged on one question. Should individual social enterprise be weeded out completely? Should they only support social enterprises owned by groups, for instance honey collectors or farmer federations that create and provide services affordable to the poor? “The Trusts handle public money. It cannot be used to make the owners of these enterprises rich,” says Sanjiv Phansalkar, programme leader at SDTT.

But there was evidence on the ground that favoured micro-enterprises in the form of people like Bhavari Devi. She heads Shudh Jal Ghar Samiti, which sells filtered drinking water to the rest of her community in Savda Ghevra, a resettlement colony 30 kilometres east of New Delhi.

Buying drinking water, at Rs 7 for a 20-litre bottle, is tough for families that earn Rs 7,000 on average each month. It was easier for them to drink free water supplied by government tankers. When Bhavari Devi showed them the math in terms of the medical costs they were incurring because the water they were consuming was unhygienic, she acquired converts. “I now sell at least 1,000 litres of water every day,” she says.

Models like this helped the trustees headed by Ratan Tata understand how social enterprise and the market model as a strategic tool can be made to work better. That seemed the best way to build a sustainable model for the long term. So, they concluded, while a Bhavari Devi ought not to be weeded out completely, models of the kind she builds ought to be robust enough to not be subverted the way the microfinance business was.

With this understanding in place, Ratan Tata started to leverage his network of relationships across the world. There is speculation the Tata trusts are exploring a possible partnership with Bill Gates. Their mandate could possibly include setting up a platform to advice philanthropists in India. The contours of this plan was said to be discussed at a closed door meeting he had with Bill Gates and Azim Premji of Wipro among others. “Though we have institutions that offer advice on philanthropy… their repository of knowledge and experience set them apart, from which others can learn,” says Sachin Sachdeva, the India director of the UK-based Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

The one who controls the senses

by the mind and intellect

and engages the organs of

action to Nishkam Karma-yoga is superior, O Arjuna

Ratan Tata’s predecessors had their hearts in the right place. That is what prompted them to fund the setting up of iconic institutions like the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) and Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). That said, the difference though between what his predecessors did and Ratan Tata wants to do is a very fundamental one.

Until recently, partners and projects were chosen mostly on “instinct” and decisions were based on “compassion”. Not surprisingly, there were only four to six officials at any time to co-ordinate with hundreds of ‘partners’ or NGOs. To Ratan Tata’s mind, it didn’t feel quite right and the system had to be changed.

“Mr Tata has been enthusiastic of products that make cutting-edge healthcare services, including long distance surgery, accessible to the poor,” says Dr MS Valiathan, a renowned cardiac surgeon and academic and one of the trustees at SDTT. “He has also been vocal in his concerns about the lack of quality research in India. He has always talked about his hope that India consistently produces Nobel laureates in science and technology,” says VR Mehta, another trustee at SDTT. The focus on research will see Tata trusts collaborating with MIT, or Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to set up research centres in the US and India that will focus on frugal engineering, aimed at serving the underprevileged, an issue close to Tata’s heart.

So the reforms, if you will, to long-time Tata watchers seem similar to what he had unleashed in the Tata group after he took over from his uncle JRD Tata. That, is the untold story. The agenda he has set himself and the trusts is to bring “focus” into what was an “instinct” driven operation. Says Krishna Kumar, his long time associate, “Mr Tata’s involvement will bring sharp focus and technological backup. The focus will be on technological disruptions.”

For instance, water is one of the areas Rata Tata wants the trust to put its energies into in the coming years. Other issues on his list of priorities include rural infrastructure and nutrition with a focus on maternal health and malnutrition. Interestingly, SDTT, the largest of the trusts, is set to complete its second five-year plan called Strategic Plan in March 2013. (See box for Tata trusts’ structure and functioning.)

The next five-year plan promises to include each of these themes and the agenda will be defined by Tata himself. Detailed notes on what SDTT does in fields like water have been prepared for the chairman. “There will be major thrust in these areas,” says Singh.

But executing all of this won’t be easy for a peculiar reason. When Ratan Tata had taken over as chairman of the group in 1991, it was spread thinly across too many sectors. He weeded out unwanted companies, ousted internal ‘satraps’ who were becoming too feudal and made an aggressive plan to go global. The outcome? From the $5 billion turnover in 1991, this year, it is expected to hit $100 billion.

What most people don’t know of is that the Tata group is structured in an entirely unique way. The Tata trusts control the group through their 66 percent majority stake in Tata Sons, which in turn is the biggest shareholder in each of the companies. Thanks to this shareholding pattern, high growth in Tata companies meant the Tata trusts grew richer.

But that prosperity was beginning to put pressure on the system. “There was a concern among the trustees, led by the Ratan Tata, that we were all over the place,” says a senior official. The reasons were clear. The trustees traditionally belonged to the Tata family, group insiders and elders from the Parsi community. At any given point of time the trusts, which acts like a funding agency, work with almost 600 ‘partners’ or NGOs through whom the money is utilised on projects that range across six broad themes.

That is why, soon after he took over,

he started to invite experts like Vijay Mahajan to form strategic plans (the Sir Ratan Tata Trust was the first to adopt it in the late ’90s). As the terms of some of the older trustees expired, Tata used the opportunity to bring in scientists like MS Swaminathan on the board. Earlier this year, E Sreedharan, the man who built the Delhi Metro and transformed the city, was inducted on board. The idea was to learn from people like them, infuse fresh ideas and improve accountability within the organisation.

This too was a departure from the past when trustees were invited on the back of goodwill and their links to the family. Now though, each trustee has a three-year tenure that can be extended. It is unclear, however, who decides on the extensions. What is known though is that those who are on the board are a professional lot. So, Swaminathan, for instance, was on the board for over 10 years before he vacated the position in 2009 because he is now an elected member of the Rajya Sabha as well.

But it is over the last five years that the changes have been dramatic. The team on the ground has increased to 25 from just six to co-ordinate with various partners. Present and prospective partners are subject to intense vetting and the emphasis on financial reporting has gone up significantly. Projects now get reviewed every six months. “If the milestones were not met by partners, grants are stopped,” says Phansalkar of SDTT.

He cites the examples of a partner who made an incredulous claim—that the bills he’d run up over the “last four years have been eaten by rats”. Vijay Mahajan chuckles as he says, “Many NGOs have actually started complaining because some of them have lost their grants.”

While that was necessary, Tata has made sure the trusts didn’t lose out on “our compassion and flexibility and more importantly, the ability to innovate and scale up projects.” A Small Grant Scheme was started in 2004 that gave grants of Rs 10 lakh to innovative projects, including one to doctors from All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) who set up a successful and replicable low-cost rural healthcare model in Chhattisgarh.

Similarly, when one of the partners told the trusts about a unique rice cultivation programme that used 30 percent less water, but increased yields by 40 percent, Swaminathan was called in for an expert’s view. “His initial reaction was that it was not possible. But he deputed a team from his research institute that vindicated the findings,” says Singh.

Today the Systematic Rice Intensification project is one of the most successful programmes funded by the trusts and is used by more than one lakh farmers across India. Its success prompted state governments like the one in Bihar to turn it into an official programme. “Unlike other funding agencies that get rigid and toe the dotted line of proposals, trusts’ officials give enough room to learn, add and omit aspects of a project as and when needed,” says Siddharth Pandey of CURE, a partner, which trained Devi and helped her set up the micro enterprise.

Because, whatever noble persons do, others follow.

Whatever standard they set up, the world follows.

The Tata trusts have influenced a new-generation of philanthropists. The Azim Premji Foundation chose education as the single cause to which it is dedicated to. The projects it chooses are implemented by the foundation, as opposed to funding those in the space.

Then there are those like Rohini Nilekani, who along with her husband and Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani, have followed the Tata trusts model. “I found it gives me a lot of leverage. I may not have the expertise to set up an institution myself. But I can still support different causes by funding and mentoring others…. It is hard to throw a stone and not find someone who has been touched by their (Tata Trusts) work,” says Rohini who supports and chairs several philanthropy organisations including Arghyam, which “promotes equity and sustainability in access to water”.

From January next year, when Ratan Tata steps into the role full time, he intends to reach out and bring together like-minded people who can draw from the trusts’ expertise and set up more agencies. He will also have the latitude to plug into areas that need money, attention and expertise, particularly in science and technology.

In the past, he had tried to improve on institutions created with aid from Tata trusts, including the Bangalore-based IISc. As chairman of its council, he had pushed for cutting-edge research there. In 2009, addressing an audience who had gathered at the Institute to celebrate 100 years of its existence, he said the institute must “demolish hierarchy”. IISc should “strive to break new grounds instead of building a fortress around itself”, he argued.

That explains why the trusts are reportedly exploring a relationship with MIT to set up a research centre that supports frugal engineering—a theme that has been close to his heart for a long time now. In fact, soon after he announced the launch of the Tata Nano, the world’s cheapest car and considered widely a milestone in frugal engineering, he was invited by US President Barack Obama to the White House.

Reportedly, Obama asked Tata to bring his expertise in frugal engineering into the US as well and collaborate with American institutions. Soon after that meeting, Ratan Tata pushed for the Jaipur Foot initiative, which until now has helped 1.2 million amputees. The push has given the Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti a better chance of entering America, where local manufacturers have resisted its entry for fear of losing market to the much cheaper Indian version.

As for the trusts’ association with the Gates Foundation, details are closely guarded for now. But by all accounts, Tata may take a leaf out of their work. Bill Gates has raised and donated almost $1 billion for research into malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Despite questions on the transparency of agencies to whom he has donated, experts in medicine say the foundation has pledged $10 billion over the next 10 years on research into vaccines in these areas. It is significant because research into vaccines would otherwise have remained stagnant. For pharmaceutical companies, this is a low margin business and isn’t a viable one.

With the trusts looking to learn and understand from international best practices, including tackling nutrition in Africa, collaboration with other international agencies is a possibility. “A stronger community of philanthropists is needed. With Tata’s involvement, we look forward to opening partnerships with the trusts,” says Ashvin Dayal, managing director, Asia, at the Rockefeller Foundation.

Interestingly, many of these foundations’ presence in India have dwindled over the years. The Rockefeller Foundation, for instance, whose projects in India are ‘valued’ at $20 million, now works through partners and doesn’t have a direct presence. The Ford Foundation, which offers grants of $15 million to Indian initiatives every year, has transited from supporting research to focusing on “exploring ways of engaging with both the government and civil society to improve the implementation of large-scale government programmes”.

India’s changing economic status, thanks to high growth rates over the last decade has prompted many agencies to concentrate on “poorer” countries, like those in Africa. But with inequality still an issue in India, where many parts of the country still do not have access to basic amenities, the Tata trusts will need to play a still larger role in the coming years.

Human beings are bound by Karma other than those done as Yajna (sacrifice).

Therefore, O Arjuna, do your duty efficiently

as a service or seva to me,Free from attachment to the fruits of work

(Additional reporting by Mitu Jayashankar)