THE REMEMBRANCE PROJECT – PART 97

Establishments are colossal beasts. Very few can take them on. It takes a different kind of mettle to challenge establishments.

The 68 year old Prochy Numazar Mehta however wasn’t the type to follow establishments blindly. Her respect towards them had to be earned.

For her, things had to make sense – with sound logic. The athlete who had won over 70 international medals including 52 gold medals wasn’t the type to just follow blindly. Justice and facts were two sacrosanct pillars of her life.

Prochy is a Parsi. Her daughter married a non-Zoroastrian but they had decided to bring their children up in the Parsi faith. Prochy would take her children to the Fire-temple until she was told not to take them. On being asked why, she was told that their trust deed prevented it and that the Trust Deed was sacrosanct.

“I studied the Trust Deed of 1915 and learnt we were to follow the Bhuggasarth priests of Navsari and Dastur Kaikobad Aderbad Dastur Noshirwan in particular. I did not know who they were and decided to investigate what happened before 1915 and why these priests were specifically named for us to follow,” Prochy says.

What began then was a journey of astute academic discovery that has now made Prochy come out with a landmark book WHO IS A PARSI that saw her rummage through the most exhaustive amount of historical evidence and documents and clearly reveal what are the facts thereby parting the curtains over what is legally true – doubts that have shrouded the community for decades.

Over six months, Prochy researched for this path breaking book that is now being referred to as a sensation.

She says “Every family in Kolkata has children who have intermarried. We were advised at an annual general meeting of our Fire temple to go to court to get a clarification as the Trustees were hesitant to take a unilateral step. At their prompting, we filed an originating summons for interpretation of the Trust Deed. I hope my research will clear the way for future generations to freely practice their religion. Presently – with the steep decline in birth-rate, the entire community is in jeopardy; it is believed, by many, that Parsi personal law is largely responsible for this plight: which is precisely the theme around which this book has been written.”

“The main question that has seen the Parsi community split right down the middle is that of interfaith marriage and conversion. The letter received by the Parsi panchayat supporting the conversion of Susaune, a French lady, and her wedding to Ratan Tata under the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act was signed by religious scholars and some of the most eminent members of the community. I had done a great deal of research and at the prompting of the late beloved Noshir Tankariwalla, the senior Trustee of the Fire-temple I wrote my first book Pioneering Parsis of Calcutta. During lock down I decided to put all my remaining research into a second book,” Prochy says.

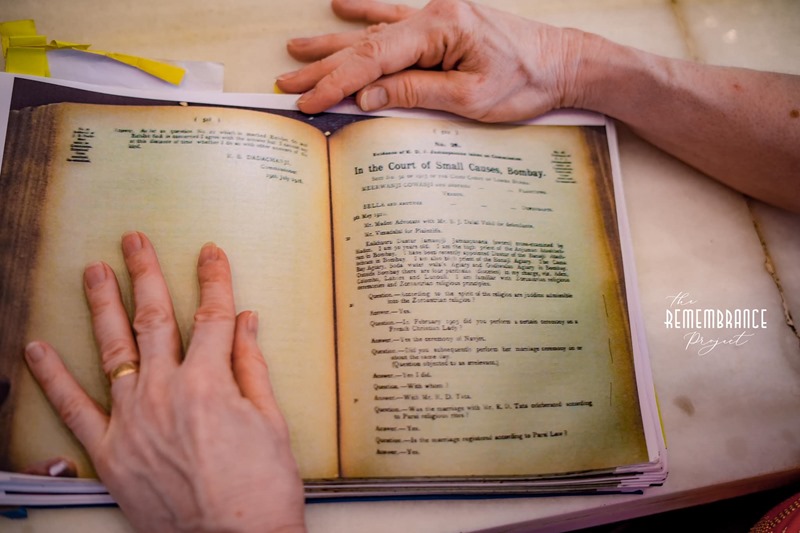

“A lot of research went into Who is Parsi. I bought books and searched internet archives for information. The most valuable source of information was the Saklat vs Bella document procured from the Privy Council by Mitra Sharafi, the legal historian of the University of Wisconsin. It gives the views of priests and the trustees of the fire temple at that time. It has letters, articles in newspapers and magazines showing the support the priests and Ratan Tata had from his friends and associates. I wonder what the views of their descendants are”

The Book has been a true revelation and has for the first time ever come up with the most exciting insights on a community revered for long in India.

“It is a revelation that so many of our present practices that we are told have been sacrosanct from time immemorial, are diametrically different from those practiced just a hundred years earlier with the sanction and active participation of High Priests and Scholars of those times. To separate fact from fiction is really difficult but fortunately we now discovered court records’.

“Similarly, no one seems to be aware of the fact that it was the head priests of the community who had once led the call of going “back to the original religion”. Research shows that it was a movement driven by learned priests and the educated members of society. Logic says that which was a religious duty or a tenet of the faith in 1908 has to be the same today. It was a pious duty to take care of an illegitimate child. To destroy it or give it up to the custom of its father was a great sin. Conversion was a tenet of the religion; in fact, it was an enjoined duty; prostitutes’ children must be accepted into the community. The Rivayats tell us to convert slave boys and girls and servants. Zoroastrianism is a Religion for all mankind, said all the priests and scholars. Are we following any of these today?

So what are some of the books most interesting revelations:

The first is that Parsis have been in India since 500BC. “We were not an affluent community. We came as refugees and automatically lived with the poorest. In fact our language is a mixture of Persian and Dubra-gujarati; We amassed great wealth but at a tremendous cost to personal life, since traders and voyagers had to be away from their families for many years. Often men would have two families, one at home and another where they stayed for years on end for business purposes. But all children, legitimate and illegitimate were accepted into the community; Ratan D Tata married a French Christian lady. She was first converted to the Parsi Religion by the Head Priest of the Bhuggasarth sect (The priests the Kolkata Fire-temple have to follow) and then her wedding to Ratan Tata was registered under the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act. JRD Tata was their son. The Special Marriage Acts caused a lot of confusion. Under The first one in 1872 interfaith couples could register their wedding but would have to make a declaration separating themselves from their religions or convert to the same religion”.

“A Parsi could marry a Parsi under the Parsi Marriage Act. Under the Special Marriage Act a Parsi could give up his or her religion and marry an alien or the alien could convert to the Parsi religion. Susuane converted and became a Parsi and married Rata Tata under the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act. However Ratti Petit converted to the Muslim religion and married Mohammed Ali Jinnah. In 1954 a new Special Marriage Act was enacted where for the first time inter-married couples could keep their own religion after marriage. It was only after 1954 that interfaith marriage became a reality and their legitimate children having a choice of religion became a possibility”.

Prochy has also tried to narrate stories and records of the past which show what apparently insurmountable difficulties the Parsis had to overcome at various stages of their history, particularly in the absence of a fixed set of laws to fall back on. The census of Parsis in Bombay in 1864 pegged the Parsi population at 49,201. The professional breakup showed no Parsi beggars but there were 5,328 servants and 1,641 cooks, 180 hawkers, 176 water carriers, 7,180 writer accountants, 6,149 merchant banker and broker and 41 prostitutes amongst a total of about 70 listed occupations. They show that dignity of labour was a hallmark of the Parsi community and throw up many interesting details. For example, there would be a ‘leechman’ whose task was to apply leeches to suck the blood of a person as a kind of medical treatment”.

“History books tell us that Parsis were ignorant of their religion till the middle of the 19th Century having lived among the Hindus for hundreds of years. In the second half of that Century, there was a general cleansing of the religion to remove the Hindu customs being followed. It was foreign scholars like A V W Jackson, Martin Hauge, Friedrich von Spiegel, James Darmesteter, Lawrence Mills and others who translated and studied the Avesta and then taught the priests the true essence of their religion and its history. Dastur Dhalla, the high priest of Karachi, for example, was sent by the community on a sponsored visit to Columbia University to study under Professor Jackson. Dastur Hoshang, the high priest of the Deccan, studied under Martin Hauge at the University of Poona. Dastur Darab Peshotan Sanjana, high priest of the Wadia Atash Behram, was also a student of Professor Jackson, while K R Cama studied under Spiegel at the University of Erlangen in Germany”.

“Another key development that brought about a paradigm shift in the Parsi community in the mid-19th century was that trade links with China brought immense wealth into a section of people and the power centre shifted from the priests to the Sethias (rich people). The two court cases, Petit vs Jeejeebhoy and Saklat vs Bella highlighted this, too. In both conflicts, it was the rich Sethias who objected to the navjotes being performed by high priests”.

“At the turn of the century, a new mystical movement within Zoroastrianism started gaining wide acceptance. Known as Ilm-e-Khshnoom (the Science of Ecstasy), it was spearheaded by Behramsha Shroff from Surat, who had learnt mystic and esoteric practices from the Abed Saheb-e-Dilan, living in the Caucasus Mountains. There were also the Theosophists, another small group within Zoroastrians which had caught the imagination of a few Parsis. This created a deep chasm within the community. The priests and other members of the community who wanted to go back to Zoroastrianism in its pristine purity were labelled Reformists. And the ones who followed the new trends of Theosophy and Ilm-e-Khshnoom and wanted to follow religious practices aligned with the Hindus, came to be called the Orthodox. As would be clear to any perceptive reader by now, in actuality it was the Reformists who were the true Orthodox,” Prochy adds.

“Then there are other aspects of our history that need to be illuminated for modern day readers. For example, the miserable condition of our co-religionists in Iran and their rehabilitation in India is a story not known to many. Thousands of poor Iranians were accepted into the community in India, no questions asked about their ancestry,” says Prochy, who has an incredible story of her own.

She took up athletics after her children Sanaya and Jahan were born.

“I had just run in the parents’ race in Sanaya’s school and I was surprised to find my timing was equal to the State Championship being held at the same time. This started my training seriously in Athletics. I took part in the state level and the national level breaking all records. It was a great feeling. I stopped competing after my granddaughter Samara was born. But I still love to practice daily. I still have the Asian Record in the 400 mts and Triple jump in the women 45+ age group. My long jump and 800m record in the All Parsi Meet which is held in Mumbai, for women over 18, still stands,” she says.

Prochy’s name at birth was Pouruchisty. The name of the youngest and favourite daughter of our prophet Zarathustra. But it was unpronounceable.

“When I started school my teacher Mrs Demelo immediately changed it to Pretty. My mom decided to truncate the name to Prochy rather than be stuck with Pretty. This name was further Indianised by force by my Hindi teachers in school who would insist on calling me Prachi. Going so far as to correct the spelling of my name. Prochy I am now. I would have opted for maths honours in Jadavpur University but it was the time of the Naxalite movement, and I was safely parked in Loreto College and did English Honours. Sports, basketball and hockey took up most of my spare time. My husband Noomi and I became a couple when he was 17 and I was 16. I remember that I did not know the Hindi alphabet and was suddenly being asked to learn Sanskrit slokas”

Prochy runs one of India’s most successful outdoor marketing firms Selvel.

“Our house was also our company (Selvel) office. Our bedroom would become an office room in the day and our dining table was used by the staff too as a large desk. We would come back from school and study with office staff. One would double as my Bengali teacher while another would teach me art. We would be encouraged to do any kind of office work. Drawing hoarding site-plans or doing some colouring,” she remembers.

Talking further about her book, she says “Two outdated court cases in 1908 and 1915 colour the opinion of the community even today regarding who is or is not a Parsi. The two Special Marriage Acts are mixed up in the minds of most Parsis, who imagine the Act of 1872 is still in force. The High Priests Dastur Kaikobad and Dastur Kaikhusu Jamaspi of the Bhugasarath sect, who performed the religious ceremonies in both the cases accepted all persons initiated into the faith as Parsis. However, The judges, while confirming a) that conversion is a tenet of the religion and b) that the child of a Parsi mother and non-Parsi father is entitled to be initiated into the religion, attempted to differentiate between the words Parsi and Zoroastrian by aligning the word Parsi with a) race or b) caste”.

“Strangely the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act of 1936 does not refer to race or caste at all. This Act finally (I say finally, as the word Parsi has not been defined earlier) identifies a Parsi as a Parsi Zoroastrian. It does not mention race or caste”.

Sadly even today, Parsi women in an interfaith marriage and their children often face discrimination.

Prochy ends by saying “The research presented in this book under the guidance of Mr Fali Nariman was started for personal reasons but now I hope it will become a clarion call for re-establishing the rights of our inter-married women and their children. In ‘Who is a Parsi’ I show that there is no religious or social reason, nor ancient custom to discriminate against them. In this book I have photocopied many pages from a judgement not revealed before. Saklat vs Bella has 1000 pages of court records. Bella was the daughter of a Parsi mother and non-Parsi father. Her navjote was performed by Dastur Kaikobad (the priest the Kolata Fire-temple is to follow). He was cross-examined in court and stood firm in his beliefs. In fact he was recognised as being amongst the most learned priests in 1915. In 2011 we were 52,000 strong. With 4 deaths to every birth recorded, we are disappearing. In addition, 50% of all marriages are interfaith. So, we are practically rejecting 25% of the future generation and racing even faster into extinction”.

So what is Prochy’s motto in life?

“My motto is ‘Do it now.’ If I think of something I need to immediately take action. Sometimes I do work in haste”.

What is her advice to other women?

“Don’t be afraid to live your dream. Don’t take ‘no’ for an answer. Always look for a solution to a problem and take action. Don’t let anyone tell you- “Girls can’t do this.”

Keep moving forward to realise your dream. Take each hurdle calmly in your stride. Look at failure as a stepping stone to success. If you keep moving forward you will end with success”.

How did the Remembrance Project make her feel?

“The ‘Remembrance project’ is a wonderful idea to bring ordinary women into the limelight. It reveals that even small acts of kindness can make a big difference and affect the lives of others,” she ends.