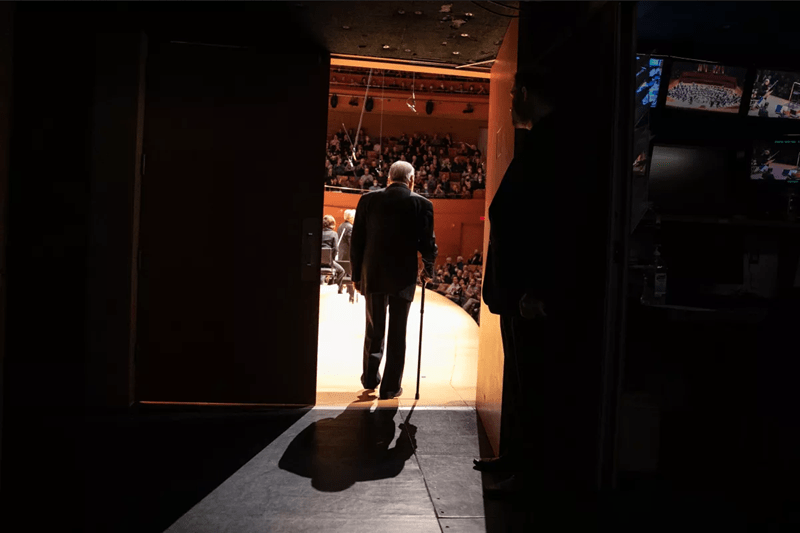

Zubin Mehta walks onstage more slowly than he did in his youthful, dashing days and is helped by a cane. He conducts sitting down. Sunday afternoon at Walt Disney Concert Hall, his arm movements lacked ostentation and could barely be seen from behind. What hasn’t changed is the Mehta Sound, something so bold and individual it requires a formal name. The Los Angeles Philharmonic had a majesty that only Mehta can get. At 86, he needs no flamboyance. His mere presence is enough.

That presence was felt from the moment the stage doors opened. The crowd began cheering before the conductor could even be seen. By the time he reached the podium, not only the orchestra but most of us in the hall were on our collective feet. Mehta has endured health problems in recent years, but this performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 3, at an almost brisk 96 minutes, displayed the quintessential majestic grandeur of the Mehta Sound. The cheers at the end were like those for a rock concert.

Article by Mark Swed | Los Angeles Times

Zubin Mehta walks onstage to conduct Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at Walt Disney Concert Hall. (Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

The Mehta Sound always encompasses massed brass and big percussion. Here, too, double basses and cellos resonated like sonic pilings dug deeply into the symphonic earth, becoming the foundation of the longest symphony in the standard repertory.

Everyone onstage appeared galvanized by Mehta. Andrew Bain’s potent horn call that opened the Third instantly called the audience to attention. Marc Lachat’s oboe could have been the jolting voice of a wild animal in the jungle. All the many solos in the symphony — be they flute, clarinet, violin, trumpet — were Mehta-ized. That also went for the strings, the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s women’s chorus, the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus and the amber-toned Gerhild Romberger, who sang the short alto solo about human suffering.

In six movements, the symphony is a vast meditation on life and nature, comprising our angst and our enthusiasms. The finale is a long slow movement that offers a swelling thanksgiving for the privilege of being alive.

Where does Mehta Sound come from? When I asked him about it in late January at his Brentwood home, he was nonchalant. He has said that in his 16 seasons as music director of the L.A. Phil, from 1962 to 1978, he always had the raptly beautiful sounds of the Vienna Philharmonic in his mind, as heard in the city’s glorious concert hall, the Musikverein.

In fact, Mehta created something quite different. No one has ever mistaken the acoustically duller Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, which Mehta opened with the L.A. Phil in 1964, for the Musikverein. The spectacular recordings Mehta made with the L.A. Phil in UCLA’s Royce Hall were engineered to produce a kind of wide-screen, Technicolor orchestral effect that first revealed the extraordinary impact that Mehta now achieves in his annual visits to Disney as the orchestra’s conductor emeritus.

Mahler’s Third was Mehta’s last recording with the L.A. Phil. He taped it in March 1978, three months before the end of his final season with the orchestra. That fall he decamped to the New York Philharmonic. By the time the two-LP set was released in May 1980, Mehta was already making slicker, less vital recordings in New York. Meanwhile, the L.A. Phil had been given a new identity by Carlo Maria Giulini, the poetic Italian conductor. The Mahler set got little attention.

It had been a long time, 45 years to be exact, since Mehta had performed Mahler’s Third with the L.A. Mehta told me that he simply felt like doing it again. His stamp is dissimilar to that of Esa-Pekka Salonen’s, who happened to choose Mahler’s Third to open his first season as music director of the L.A. Phil in 1992 and went on to make a luminous recording it a few years later with the orchestra. Gustavo Dudamel luxuriated in his own warmly sympathetic recording of it with the Berlin Philharmonic in 2014.

For his part, Mehta has made two more recordings of the Third. One, in 1993, was with the Israel Philharmonic, during his half-century tenure as the orchestra’s music director. Here the symphony has a hair-raising, scrappy authority. The other was a robustly magisterial live recording made in the Musikverein, as part of a tour with the orchestra of the Bavarian State Opera (where Mehta served as music director from 1998 to 2006). Mehta has also had been chief conductor of the Teatro del Maggio Musicale in Florence, Italy, and the Palau de les Arts in Valencia, Spain.

But L.A. and New York made Mehta the commanding Mahlerian he has become. The arresting analog engineering of the Royce Hall sessions are where you witness the marvelous Mehta Sound — where each sonority has a personality, even a kind of chutzpah. Mehta said that when he then programmed the Third in New York, he studied it with Leonard Bernstein.

“Lenny came to my performance with the New York Philharmonic,” Mehta recalls. “Afterwards we went to his apartment, and we talked about it. He told me that the last movement had to be 26 minutes. ‘Yours was faster,’ he said. ‘It’s not fast. The last moment is very slow.’”

In his recordings and at Disney Hall on Sunday, Mehta’s last movement stubbornly remained between 23 and 24 minutes. Mehta doesn’t go for Bernsteinian transcendence, but rather outward glory. Mehta doesn’t prepare his climaxes, he stuns you with them. He insists upon awe.

“Bernstein had many things to tell me, and I appreciated it a lot of it, especially about how to deal with the orchestra and about interpretation. He told me what he liked and what he didn’t like. He once came to my performance of Mahler’s Fifth and didn’t like it.”

Shortly after becoming music director of the L.A. Phil and not long before her death in 1964, Mehta visited Alma Mahler, the composer’s widow and a composer in her own right. “I didn’t know her well, but I speak Viennese,” he said referring to distinct Viennese German pronunciation, “so we got along very well, and she showed me everything, with all her different husbands, including architectural designs, models, autographs,” notably from her later spouses, including the architect Walter Gropius and novelist Franz Werfel.

“She made me miss my plane to Paris,” Mehta continued. “I had a rehearsal in Paris I had to cancel. She just held my hand and wouldn’t let me go. I asked her so many questions about Vienna.”

However, Mehta says he did get to know Anna Mahler, a noted sculptor and the second daughter of Gustav and Alma, very well. “Anna used to construct huge statues,” Mehta says. “She had the death mask of her mother.”

“I took her once to a play at the Mark Taper Forum,” he recalls. “She fainted during the intermission of the play. Suddenly this man came to help me. I saw it was Charlton Heston. He didn’t know who she was, and I didn’t know him. He just saw a woman falling and so he wanted to help.

During our conversation back in January, I was tempted to ask him about the fictional Lydia Tár’s grotesque performance of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony in “Tár.” But more pressing at the moment: his views on whether Gustavo Dudamel might become the next music director of the New York Philharmonic, which everyone in New York seemed to believe. Although Mehta’s tenure with America’s oldest orchestra was rocky at times, particularly from some journalists who found him flashy and superficial, he wound up lasting 13 years as its music director, longer than any other.

Did he think Gustavo Dudamel would go to New York? No. Paris and L.A. made more sense to Mehta, who has seldom been back to New York. No conductor after Bernstein (that includes Pierre Boulez, Mehta, Kurt Masur, Lorin Maazel and Alan Gilbert) maintained much of a relationship with the orchestra. Mehta, on the other hand, has appeared regularly with the L.A. Phil for more than six decades.

In a follow-up phone call after the news that Dudamel had, indeed, accepted the appointment to become the New York Philharmonic’s music director beginning in 2026, I asked if Mehta had any advice for Dudamel. He didn’t, explaining that much has changed over the years and that he currently had little contact with the orchestra. But he had confidence that Dudamel would win the players over.

Other than New York, Mehta has kept his ties with all his former orchestras and opera companies, along with the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics, which he conducts regularly. “I promised when I left the Los Angeles Philharmonic that I would keep coming back, and I have,” he says. He has kept his main residence in L.A. and has become seemingly more beloved with every passing year and appearance.

Next week he returns to Florence for a production of “Carmen.” He is now preparing to conduct his first “Lulu” next season in Florence, with William Friedkin directing Berg’s opera. At least that’s the plan. The Maggio Musicale, which is so devoted to Mehta that it named one of its theaters after him, is in crisis. Its superintendent, Alexander Pereira, recently resigned in the wake of a fraud investigation over his use of the company’s credit card. A civil servant has been appointed to replace him. Mehta says he’s sorry to see Pereira go and will meet the new head, Onofrio Cutaia, for the first time when he’s back in Florence.

Mehta’s longstanding connection with the Israel Philharmonic also continues, although he is concerned about the political havoc brought on by the new far-right government. While no fan of Benjamin Netanyahu, Mehta says that he mainly got along with the various ministers of culture until the last one. But he looks with dismay at the chaos that now roils Tel Aviv, where orchestra players are as likely to be found in the streets demonstrating as they are rehearsing.

Mehta also discounts a rumor that health problems have caused him to cancel some appearances in Munich in June. “Last year, I worked from January to November nonstop,” he explains. “And I couldn’t look at music anymore.”

Mahler’s Fifth once again reared its head. “I started looking at the Mahler Fifth Symphony, which I’ve done more than 50 times. I couldn’t. So, I canceled. I was supposed to also have a huge tour of Asia, which they canceled because of expenses. So, I took advantage of that and said, ‘let me take two months off.’”

Mehta says he will happily spend the time off in L.A., where he is most comfortable. While his career still centers in Europe and Israel, as it has since leaving the New York Philharmonic in 1991, he always returns home, where he will now have the time and peace to study “the very difficult ‘Lulu.’” And while he rarely conducts anywhere in U.S. other than L.A. these days, he remains ever faithful to his old orchestra. This weekend, he leads an imaginative psychedelic program of “Ancient Voices of Children,” written in 1970 by George Crumb, a composer Mehta championed in L.A. and New York, and Berlioz’s “Symphonie Fantastique.”

In December Mehta has two more weeks with the L.A. Phil, focusing on Beethoven and more Mahler (Symphony No. 1). What he has always missed in L.A., though, is the opportunity to conduct opera. It’s always been central to his work, and it’s something he has always excelled at.

Los Angeles Opera has yet to stage “Lulu,” I note. Mehta doesn’t say anything and just gives me a quizzical smile.