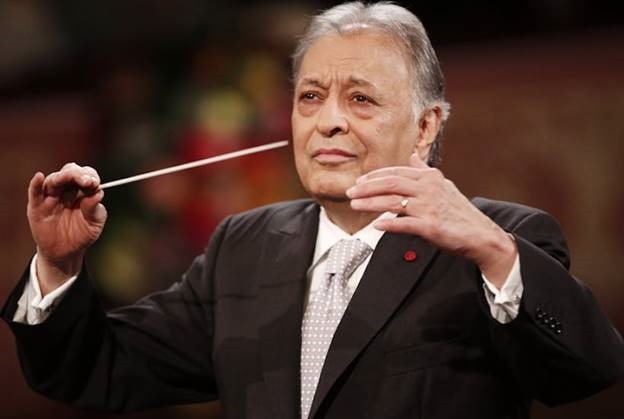

It’s a marvellous thing that the great Indian conductor Zubin Mehta will be wielding the baton for that illustrious group the Australian World Orchestra at Melbourne’s Hamer Hall on 31 August and on 2 September at the Concert Hall of the Opera House. The performance will be of the Tone Poems of Richard Strauss, those thundering and crescendoing pieces that make such a histrionic claim to fame and that seems appropriate given that Zubin Mehta who has done everything was the wunderkind of all wunderkinds, the stripling who became the principal conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic when he was 26 years old, who also happens to have conducted Puccini’s Chinese operatic spectacular Turandot before the walls of the Forbidden City in Beijing.

Article by Peter Craven | The Spectator

But Zubin Mehta has done everything. He recorded with Frank Zappa and he recorded with Ravi Shankar (the sitar player who wrote the introduction to his memoirs). He conducted the 1990 performance of Tosca that was shot in real time in the appropriate Roman locations with Catherine Malfitano, Placido Domingo and the great Ruggero Raimondo as the black-hearted villain Scarpia: bones were broken but under Mehta’s baton the show went on.

He was born in Bombay in 1936 to an upper-middle-class Parsee family, that smallish religion that hails from Persia and is a form of Zoroastrianism. He was educated by the Jesuits at Saint Mary’s (where one of the priests taught him counterpoint) his home was full of music because his father was a violinist who eventually founded the Bombay Symphony Orchestra and who taught him violin and piano while filling the house with the distinctly monaural sound of old classical 78s. He drifted into medicine but music would always hold his ear captive. And so at the ripe old age of 18 he was in Vienna and studying under Hans Swarowsky, who recognised the daimonism in Mehta which was the clue to his status as a prodigy, and this was also sharply noted by John Culshaw, the most progressivist of record producers who brought out those legendary Decca recordings of Mehta spanning the canon as if it were a personal imperium with which the conductor had an intimacy as if by birthright. Swarowsky ensured that Mehta knew the glories of music – Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Wagner – but he also reminded Mehta that Schoenberg was around the corner and many years later he would do a Moses and Aaron with the Bavarian State Opera. He was that musical paradox, an inflamed intellect. Vienna was his blacking factory. His first taste of it was to hear how Karl Boehm could conduct Mozart but the fact that Mehta was such a far-flung inheritor of the Viennese luminesence made him, almost from his musical cradle, a quick study.

He has always said that he cottoned on to the way Furtwangler had somehow heard the thing behind the notes and between them. He also escaped the envy-engendered fate of underestimating von Karajan who paid him the great compliment of offering him an unforgettable piece of advice, ‘Don’t be routine.’ He warned him of following in the footsteps of a famous conductor whose name Mehta is too gallant to repeat.

In his early dirt-poor days in Vienna, Mehta kicked around with Daniel Barenboim and with another distinguished conductor-to-be, Claudio Abbado, but it was Jacqueline du Pré, Barenboim’s cellist wife who said that Mehta provided a magic carpet for you to float on. But he also performed Schubert’s Trout Quintet with her, with Barenboim, Pinchas Zuckerman, and Itzhak Perlman with Mehta playing double bass himself – there’s a 1969 doco of this poignant occasion. She died so young.

History does not record – at least with a Culshaw-like mastery of the dynamism of stereo as an electrifying dramatic medium – quite how Wagnerian Solti’s cry of rage was when he learned that he was supposed effectively to share the Los Angeles Philharmonic with Mehta but he resigned forthwith. Mehta ran it from 1962 to 1978 and rapidly entrenched himself as one of the world’s greatest conductors.

He always believed that music was a mystery that had to be envisioned: there was a visual correlative to how it was meant to work and if you could somehow see this the vision could be perceived as sound. This sense of a visionary mystery is there in the way he transfigured the Montreal Symphony Orchestra and it was there (with bells on, so to speak) when he became Chief Conductor of the New York Philharmonic, a gig he kept from 1978 until 1991.

Other great conductors were always a bit fearful of having Mehta as their guests or stand-ins perhaps because of the way he combines extreme technical precision with that profound quality of creating fantasy, of engendering the sheer dazzle of a fully imagined world which only happens to be expressing itself in music. He has certainly had the most lustrous possible career. He bought a Hollywood house from Steve McQueen’s widow and she said to him, ‘You’ll never move.’ He was the conductor of the Three Tenors concert with Pavarotti, Domingo and ‘Carreras: he did the Gershwin for Woody Allen’s Manhattan. If he needed actors to read poetry he would get Vanessa Redgrave or Gregory Peck or Louis Jourdan to do it and he loved the way Jourdan could jump from quoting Baudelaire to Shakespeare and he denied that he was a stargazer. ‘Some actors,’ he said, ‘just liked music.’

Zubin Mehta was made the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra’s musical director-for-life though he could also sometimes play them his beloved Wagner, which they accepted. He says the Israeli position is close to his heart and at the same time he has done everything he can to befriend Arab musicians as his soulmate Daniel Barenboim has. He played Mozart’s Requiem in the ruins of Sarajevo in 1994. Zubin Mehta seems completely at home in a career which is also a vocation. In the late 1990s he became head of the Bavarian State Opera and it’s fitting that in his old age he should be conducting Ein Heldenleben about the soaring spirit of youth.