The ancient religion is estimated to have less than 100,000 practicing followers worldwide.

By Eric Killelea, Religion ReporterFeb 6, 2025

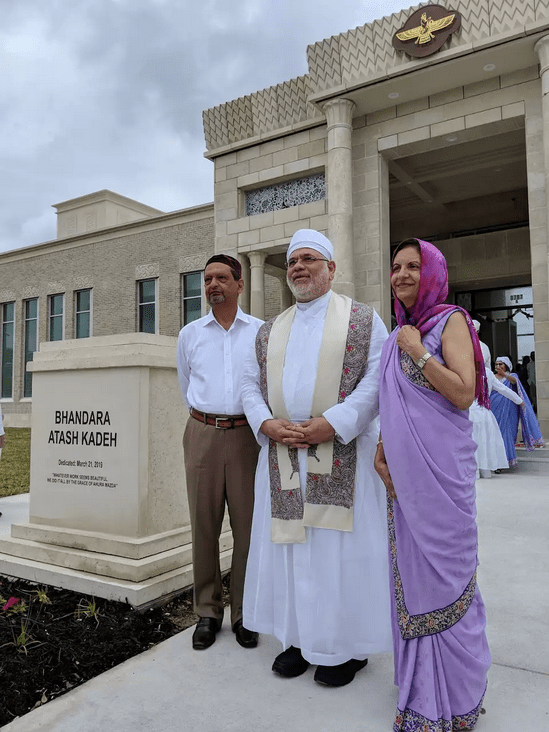

The Bhandara Atash Kadeh in Houston. Courtesy of Bhandara Atash Kadeh

Mahtab Dastur is an 18-year-old student at Rice University in Houston. In one of the most culturally diverse metros in the country, Dastur also happens to be the only undergraduate practicing the ancient religion of Zoroastrianism.

Zoroastrianism has about 710 members in Greater Houston and 1,100 in Texas, according to the Zoroastrian Association of Houston. The U.S. and Canada have a combined population of roughly 25,000. The religion that once claimed millions of followers at its height now has a global count estimated at fewer than 100,000.

At the 18th North American Zoroastrian Congress in Houston, Dastur and about 700 other adherents attended meetings crafted around the theme, “Generation Z: Propelling Zarathushti Resurgence.” Dastur hosted her own panel featuring a Canadian fashion designer and a California-based physical therapist, teacher and political policy director who proposed reworking the religion’s public brand in a time of disinformation and dwindling membership.

“The religion’s numbers are declining,” Dastur told Chron via phone after the association’s congress at the Royal Sonesta hotel between Dec. 29 and Jan. 1. “In recent years there has been a surge in the North American community involvement. How to combat the declining numbers has been a point of contention for many years, and there are different perspectives on how to do so.”

Some of the Zoroastrian panelists advised believers to share their art and music on social media platforms. Others recommended they make their voices known by volunteering at hospitals and homeless shelters. Parshan Khosravi, a Iranian-American Zoroastrian who unsuccessfully ran for a city council seat in Laguna Hills, Calif, in 2022, said he wanted Zoroastrians of all ages to engage in Texas politics. Christians, Muslims and Hindus have already won seats in the state House and Senate. So, why not Zoroastrians?

In Texas, where politics often fuses with religion, Khosrvavi believes Houston’s Zoroastrians should reach out to lawmakers about political topics that might impact their communities, such as immigration—especially those who have family ties to Iran, India and Pakistan and are known for working in the metro’s medical and technology hubs.

“The way of survival for the last thousands of years has been by assimilation but also largely has been by staying quiet and staying in our lane,” Khosravi, 31, said, emphasizing the difficulties Iranian-born Zoroastrians face when speaking up about politics in America. “Because of the sacrifice of our parents, we now get to be more outspoken.”

Founded more than 3,000 years ago, Zoroastrianism is one of the oldest monotheistic religions. It influenced later religions that believe in one supreme being, including Judaism, Christianity and Islam, per reporting by National Geographic. According to tradition, the Zoroastrian god, Ahura Mazda, revealed the religious tenets to the prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster in Greek) in Central Asia around 1700 to 1000 B.C. With a history cycling through periods of growth, conquest and revival, Zoroastrianism flourished around 550 B.C. in the Achaemenian Persian Empire. In 330 B.C., 20 of the 21 books of the Avesta, Zoroastrian holy scripture, were allegedly destroyed by the Greeks in Alexander the Great’s invasion of the Person Empire. Zoroastrianism still remained dominant in Persia until Arab Muslims conquered the region in the 7th century. Along the way, Zoroastrianism spread into China and India and eventually worldwide.

Famous Zoroastrians who believed in the religion’s teaching of “Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds” included Queen’s late rock band frontman Freddie Mercury and Jamshedji Tata, the late founder of the Tata Group, India’s largest business conglomerate. Zubin Mehta, the music director emeritus of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra who conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic, is also Zoroastrian. Several young Zoroastrian actors from India, including Amyra Dastur and Shreas Pardiwala, have recently gained recognition on social media as well.

Houston’s Bhandara Atash Kadeh. Courtesy of Aban Rustomji

In 1976, the Zoroastrian Association of Houston organized with the goals of promoting the “religious, social, and cultural aspects of the Zoroastrian faith.” It launched with only 15 members, but that number grew over the years as more Zoroastrian immigrants settled in Houston. In 1998, the association built the Zarathushti Heritage and Cultural Center on West Airport Boulevard in southwest Houston. The center originally only had a small prayer room but has since added Sunday school rooms to teach youth about the religion and its traditions.

After more than a decade of planning, the association opened its fire temple, called the Bahandara Atash Kadeh, next to the center in 2019. The 7,000-square-foot structure was the first temple of its kind built in the U.S. Association members said the temple would meet the spiritual needs for second-and third-generation Zoroastrians. At the time, a “Parsi” high priest, a term used for the religious ethnic group in India, discussed the importance of the religion’s existence and asked whether “Zarathushtis want to survive and have the will to survive.” The Houston Chronicle then reported that about 1,000 Zoroastrians were in the metro and yet only 190,000 worldwide, attributing the low numbers in part to Zoroastrians marrying people from outside of the religion and having low birth rates.

For Zoroastrianism to survive in Houston and elsewhere, Mahtub Dastur and her Gen Z panelists said it was necessary to teach members and non-members alike about their religion and dispel rumors about their faith. In addition to outsiders condemning Zoroastrianism as a cult, the general public has often misunderstood the religion’s relationship with fire, as some fire temples house flames that are tended around the clock for millennia. (The Houston fire temple featured the first continuous, wood-burning fire in North America; the fire in the temple in Yazad, Iran is said to have burned since the 5th century A.D.) Dastur claimed that an AP history teacher at her high school in Houston once described Zoroastrians as “fire worshippers”—an inaccurate label often perpetuated by news media.

“We worship Ahura Mazda (God) through fire,” Dastur explained. “We respect the fire as a very pure creation of God. Fire itself is very cleansing and clarifying. It’s a source of light, warmth, and heat. It’s important to human beings, and we believe it to be an essential part of what the Earth holds and what the Earth is.”

Vehishta Kaikobad, a longtime member of the Zoroastrian Association of Houston and senior docent of at the Museum of Fine Arts, said “light is a means of life.”

“Just as the cross is sacred to the Catholics, so is the fire of flames sacred to Zoroastrians,” Kaikobad added.

A donor couple and High Priest from India stand in front of Houston’s Bhandara Atash Kadeh. Courtesy of Aban Rustomji

Dastur has been extremely involved in Houston’s Zoroastrian community. Both her father and brother are priests while her mother is a Sunday school teacher. Dastur has served in faith-based organizations and is a member of the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America (FEZANA), a non-profit religious group that connects at least 27 associations in the U.S. and Canada. While Dastur is “grateful” to have found a “close-knit” Zoastrian community herself, she believes part of the reason for the low membership numbers in the metro and across the country is due to how spread out everyone is from one another. It takes her about an hour to drive from her home in the metro to the local fire temple.

That’s partly why Dastur has been talking with Rice University’s administrators about hosting a Zoroastrian event on campus this year. (At least two Zoroastrian students are enrolled at Rice.) Bahrom Firozgary, a Rice alumni who played basketball for the Rice Owl’s, once organized a similar event dating back to 2013. Rice, home to numerous religious ministries including Houston’s Baptist Church, Sri Meenakshi Temple and the Islamic Society of Greater Houston, doesn’t have Zoroastrian ministers on campus. However, the private university’s archives do include oral histories of the Zoroastrian community.

After the congress in Houston, Khosravi, the political director from California, said he wanted Zoroastrians to create “a structured, protected brand” to preserve their religious beliefs in the cosmic battle between good and evil and the idea that good deeds should be performed without expectation of reward. “We want to make sure that Zoroastrians are recognized as strong contributing members of society here in the United States,” Khosravi said. “We are a religion in danger of extinction, officially, by the markers, and yet the only place in the world where we keep our numbers increasing is North America. That is because of the promise of opportunities, because of the promise of freedom.”

Still, Zoroastrian elders have argued that the religious community has already made connections with Houston politicians, interfaith groups, academia and cultural leaders. They described how Mayor John Whitmire proclaimed Zoroastrian Days of Houston would be celebrated between Dec. 29, 2024 and Jan. 1. On behalf of the mayor, City Councilor Letitia Plummer, a Muslim with Zoroastrian roots, made the announcement during the congress.

Also, the Texas Asia Society, an educational nonprofit in Houston’s Museum District, has been inviting Zoroastrians to its March celebration of Nowruz, the Persian New Year.

Kaikobad, who was born in Pakistan and educated at the University of Cambridge in England, recently led a discussion about the MFAH’s gallery, titled, “Divine Fire: Zoroastrianism and Ritual Purity.” “Art is one of the forms of us sharing the faith,” Kaikobad said. “I’m not a social media person. But if social media is one of the ways to educate people, I don’t have any problems, as long as the information is correct.”

Kaikobad took issue with the notion that Zoroastrians are struggling to make themselves known in this city. “We’re a small group, but we’re still a living community,” she said.

Don’t know about the practices in Middle Eastern countries, but in India 🇮🇳 and Pakistan 🇵🇰, from where the present ‘Zoroastrian’ diaspora has spread, the ‘religion’ has been appropriated as the SOLE and EXCLUSIVE POSSESSION of an ‘ethnic community’ – defined strictly

through paternal descent – the Parsis!

Such small ethnic communities inevitably die out through intermarriage; consequently as long as the religion is guarded as belonging solely to an ethnic community, it cannot last beyond the demise of that community.

Unfortunately, laudable and successful efforts to give socio political prominence to a diminishing ethnic group, is unlikely to save the religion.