The Centre has revamped Jiyo Parsi scheme to arrest the declining population of Indian Parsis. For every 150 Parsis born in a year, there are 600 deaths.

Senior citizens playing cards at Cusrow Baug | Shubhangi Misra | ThePrint

Text Size: A- A+

Mumbai, Pune, New Delhi: There was something unsettling about Navsari. Dr Shernaz A Cama couldn’t quite put her finger on during a field trip to one of India’s oldest Parsi settlements in Gujarat—until she went through her photographs. And then it hit her. There were no children. That was 30 years ago.

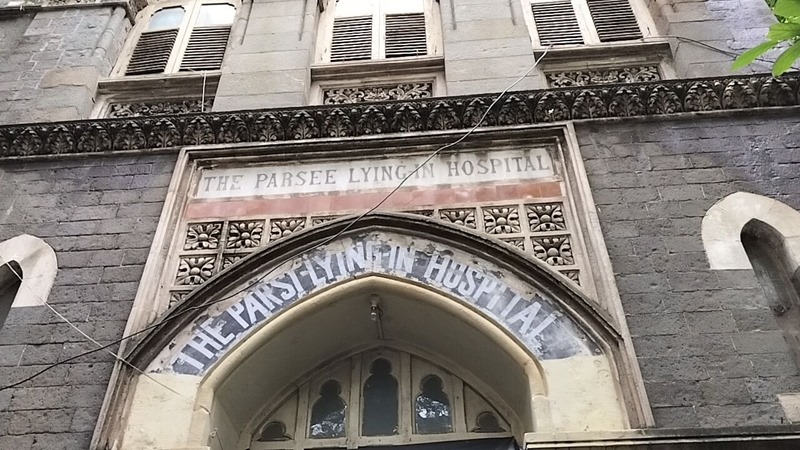

Cut to Mumbai 2023. In the busy Fort area, the Parsi Lying-In Hospital—the city’s first maternity medical centre built in 1895 and spread over 17,000 sq ft— no longer reverberates with the sound of crying babies. It lies in disuse, its brick edifice birthing moss. A silent sentinel to the crisis of numbers that India’s Parsi-Zoroastrian community is staring at.

There simply aren’t enough births to merit a massive maternity hospital. The fortnightly magazine, Parsiana, which operates out of a former ward on the ground floor of the building, regularly reminds its readers of the impending doom. For every 150 births in a year, there are 600 deaths, warns its editor Jehangir Patel. Now, these conversations are gathering momentum after the ‘Parsi issue’ and the Jiyo Parsi scheme—an initiative to arrest the declining population—came up in the Lok Sabha. Minority affairs minister Smriti Irani said that the central government’s scheme has been able to ensure 400 additional Parsi births since it was rolled out on 31 December 2022.

As per the official website, the figure stands at 403 births. But it’s not enough for a community that prioritises racial purity over demographic decline, and refuses to accept children of their women who marry non-Parsis into the fold. According to Cama, a professor of English at Delhi’s Lady Shri Ram College for Women and co-founder of the NGO Parzor Foundation, the number of Parsi children below five years (per 10,000 people) has fallen to 3.2 per cent.

The Parsi Lying-In Hospital has been dysfunctional for over 30 years | Shubhangi Misra | ThePrint

All the births under Jiyo Parsi took place when the government was working with Cama’s Parzor Foundation, one of the architects of the scheme. But in October 2022, the Centre terminated its contract with the foundation with the aim of implementing the scheme via Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT).

Despite the success of the scheme, the Parsi population in India is still dangerously low, only 57,264 as per the 2011 census. And early Jiyo Parsi campaigns tugged at the cords of these inherent fears.

“After your parents, you’ll inherit the family home. After you, the servants will,” warned flyers and print ads, which drew sharp criticism for what many saw as sexist, classist and regressive.

“I’m guessing this may have to do with the fact that Parsis live in posh South Mumbai homes and not far-flung North Indian villages,” wrote US-based journalist Anahita Mukherkee.

But for Cama, the campaign served its purpose.

“The ads were meant to shock people. They went viral and started a huge debate. It brought attention to our cause. That’s much better than dying a natural death,” she says.

Population vs bloodline

Within the close-knit community, a debate is raging on whether an increase in Parsi numbers should come at the cost of diluted bloodlines. But all is well, insist the orthodox members of the community.

“We are very happy with our numbers. We are a small tribe and don’t mind living this way,” a trustee of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet said. “There are Zoroastrians, and then Parsi Zoroastrians. Everyone may embrace the faith, but everyone cannot become a Parsi.”

At her home in South Delhi, Cama scrolls through the photos on her iPhone. Her albums are filled with smiling Parsi toddlers playing with their toys, posing in their sunglasses, and families preparing for navjots, the rite of passage when their children are inducted into the religion and wear its symbols — the sedreh and the kushti, the sacred vest and thread.

For ten years, Parzor Foundation through the Jiyo Parsi scheme has provided assistance to Parsis to help them conceive children. There are counselling sessions, monetary support and assistance with IVF.

“I have photos and videos of the cutest little first moments of various children. The first time they sit up, their first day at school, navjote… and invitations to celebrations. It is all so cute, I feel like a surrogate grandmother,” says Cama, who founded Parzor Foundation in 1999 with the aim of preserving Parsi culture and heritage.

The cheerful Cama has dedicated her life to the cause of recording Parsi oral history, preserving its architecture, facilitating research into her community’s demographic predicaments, and helping implement the Jiyo Parsi scheme.

There are three components to the government’s scheme: medical, health of community, and advocacy. The medical aspect provides financial assistance towards costly IVF treatments. Under the health of community component, funds are allocated to young couples to help them take care of their children and elderly family members. Every couple is provided Rs 3,000 per month until their child reaches four years, and another Rs 4,000 to take care of their elderly parents.

“One big reason why Parsis remain childless is because a young Parsi couple on an average has eight dependents. We realised this problem, and offered financial assistance for the elderly of the family so a couple can comfortably plan a family,” said Cama, who has published her research on the Parsis in four volumes.

Another key aim of Jiyo Parsi is to battle infertility among Parsi couples, which is addressed through funding the often expensive IVF treatments. “IVF is not just financially draining, it is a painful process both physically and emotionally,” Cama says.

To help ease the process, Parzor set up a cell in Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai with gynaecologists and counsellors on board. Parents who sought help under the Jiyo Parsi scheme could consult with counsellors who would often travel from Mumbai to wherever they were to help them. The cell isn’t functional anymore.

And though her foundation is no longer linked to the scheme, Cama keeps tabs on births. She insists that to date, Jiyo Parsi has facilitated the birth of more than 500 Parsi children.

“The figure with the government is until October 2022. Since then, according to my estimate, 130 more births have taken place.” At the same time, she worries that under the DBT scheme, Parsis will not know who to reach out to.

The lack of information which is now plaguing the scheme has Kainaz Kerawala at sea. She and her husband would like to have a second child, but she is not keen on undergoing IVF again.

“I want to go for counselling, but I don’t know where to go because now it’s DBT,” said Kerawala, who works as a nurse at a dharamshala in Navsari. She had taken help from the scheme for the birth of her first child, now five years old. She had approached Parzor after a workshop it had conducted in the panchayat.

“With the help of Jiyo Parsi, I consulted the doctor who did a laparoscopy and found cyst formation in my uterus. Later on, I went through surgery and the cyst was removed. After that I went through IVF treatment and conceived in the first go,” said Kerawala.

Assistance in IVF treatment has proved to be successful especially because the total fertility rate of Parsi women is 0.9 per woman, below the replacement level of 2.1.

A representative of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet said they have had one meeting with the government in December 2022 about the renewed phase of the scheme’s implementation but didn’t have any further information to share.

Local Parsi panchayats, too, offer Parsis financial assistance as incentives to have multiple children. The Bombay Parsi Punchayet offers around Rs 4,000 a month to help couples raise their second child, and Rs 5,000 for the third. The Surat Parsi Punchayet also awards around Rs 3,500 per month to couples having a second child.

As the city’s largest landlord controlling Parsi enclaves and 4,200 houses—according to a BPP trustee—the panchayat also provides housing to young couples looking to expand their families.

On a rainy July evening, the ageing residents of Colaba’s Cusrow Baug gather in the auditorium to play cards and bond over cups of cutting chai. In the corridors of the flats, children can be heard laughing and playing. But the fear is that one day homes will fall silent across Parsi enclaves be it Cursow Baug or Rustom Baug in Byculla or the unwalled Dadar Parsi Colony.

Cusrow Baug in Colaba is one of the Parsi residential colonies in Mumbai | Shubhangi Misra | ThePrint

Reaching out to the Gen Z

The burden rests on the younger generations, but Gen Z Parsis, especially women, are pushing back.

“I am not a reproduction machine. I’ll do what I want,” says 22-year-old Avaan Navdar from Tardeo in South Mumbai. Until junior college, Navdar did not have a single non-Parsi friend. She studied in posh Parsi schools and hung out with other Parsi girls.

“It’s not like we didn’t have Hindus or Christians in our [boarding] school, but they were day scholars and we naturally just connected with Parsis well,” she says.

She even attended a talk about the the demographics of the Parsi community globally and in India while attending an annual Holiday Programme of the Parsi community for Youth or HPY—an initiative where adolescent Parsis go for a group holiday immediately after completing Class X.

“They spoke about the importance of marrying within the community,” said Navdar. It was only in college that she started befriending people from other communities and met her boyfriend—a non Parsi. She has her parents’ approval, but it doesn’t stop nosy neighbours from calling to complain about her unacceptable behaviour.

“So many times someone or the other spots me chilling with my boyfriend and complains to my parents. Thankfully, they know,” said Navdar, the frustration and bitterness leaking into her voice.

Men on the other hand can marry a non-Parsi and have children who can enter the fire temple, celebrate their Navjot and enjoy all the benefits—monetary and otherwise—that Parsis enjoy. This goes back to a 1908 case when Dinshaw Davar, the first Parsi judge of the Bombay High Court, and Frank Beaman, a blind British judge, ruled that Indian Parsis are a “pure” caste who don’t have to accept anyone in their fold that might “contaminate” the community. The only ‘aliens’ allowed into the Parsi caste would be children of. It is entrenched in Parsi Personal Law today, but there is pushback.

A priest offers prayer at fire temple in Pune | Shubhangi Misra | ThePrint

Today, in Mumbai, the orthodox and the liberal, the progressive and the purity-obsessed clash within the walled baugs and colonies on purity, population and progressive attitudes.

“The community is changing, the BPP isn’t. That’s the bottomline,” said a young Parsi man who did not want to be named.

Children’s camps and youth organisations are an important part of the fabric of Parsi life. Organisations like the Extremely Young Zorastrians (XYZ) and Zoroastrian Youth for Next Generation (ZYNG) are geared towards helping Parsis form life-long connections with each other from a young age.

“We thought a lot of social organisations help adult or adolescent Parsis socialise, but there was nothing for children. So we started XYZ [in 2014],” says Hoshaang Gotla.

ZYNG, which organises donation drives, dance competitions, movie nights, hikes, and other activities, dates back to 2009. It began as the youth wing of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet, but was emancipated from it two years ago.

“Almost half of all Parsi marriages in Mumbai today are interfaith because young Parsis are unable to meet eligible Parsis,” said Viraf Mehta, one of the founding members of ZYNG and a trustee of the BPP. He estimates that only around 60 percent of community members in Mumbai live in Parsi-owned buildings. “The chances of a Parsi meeting a Parsi become quite low,” said Mehta.

In the last 12-13 years, ZYNG has conducted over 1,700 social events. And about 15-20 young Parsi couples have found love there. But Mehta says that’s not something to focus on.

“It’s not that our entire agenda is to ensure Parsi marriages. We just want Parsis to come together and socialise. If they find love along the way, nothing like it,” Mehta says.

Among the 20-odd Parsi youth organisations in Mumbai, Extremely Young Zoroastrians (XYZ) is the only one that welcomes children of Parsi women, claims its founder Hoshaang Gotlaa.

“Ours is not an organisation to focus on just one religious aspect. Just because someone’s father is not a Parsi, [that doesn’t mean] we don’t accept them into our fold. This isn’t something I am a big fan of,” he said.

And yes, there is backlash. “Some people will always have a problem with what you do,” Gotlaa adds.

Falling fertility rate

Nineteen-year-old film student Zayan Sangha met his former girlfriend in an XYZ camp. She was a Parsi, too, but he’s not opposed to interfaith couples. Love overrules purity just as it did when Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata married his French girlfriend, Suzanne Briere in 1902.

“For me love is love. Even though marrying within the community has its benefits, that doesn’t mean I won’t marry a girl from outside if I fall for her,” he says.

Sangha speaks for an increasing number of Alpha, Gen Z and Millennial Parsis, who don’t necessarily want to carry the burden of ‘saving’ their community along the lines of purity.

Inter-faith marriages, especially among women, are cited by Parsis as one of the major reasons why their community is on a steady decline.

But a 2011 peer reviewed study by Zubin C Shroff and Maria Castro, a copy of which is with ThePrint, concluded that consanguineous marriages cannot be blamed for reduced fertility among Parsis. Education and westernisation are the main driving factors, said the authors.

Around 36 per cent of Parsis also don’t marry at all in their lifetimes, according to Cama.

“The first drop in Parsi fertility appears to have happened around the end of the 19th century, and was related to the rapidly increasing rate of women’s education in the community after 1870,” reads the paper. The authors also noted that accepting children of interfaith couples will not have a significant bearing on the dwindling population.

According to data analysed by Parsiana, close to 50 per cent of all Parsi marriages in Mumbai today are interfaith. “There’s social acceptance of women marrying outside now. They’re not socially ostracised any longer. But there’s religious othering of women,” Vispy Wadia, president of the Association of Intermarried Parsis, said.

However, a study conducted by Dr Lata Narayan at TISS Mumbai, a hard copy of which was read by ThePrint, with a sample size of 761 respondents spread across India, only 4.4 per cent Parsis said that children of Parsi women who have undergone Navjote should be considered members of the community. The study was published in 2017.

Parsi women have also approached various high courts and the Supreme Court to ask for their right to enter the fire temples and the tower of silence.

Author Prochy N Mehta filed a petition in the Calcutta High Court in 2017 after her grandchildren were not allowed to enter the only fire temple in the city, because their father was a non-Parsi. The Federation of Parsi Zoroastrian Anjumans of India (FPZAI), an umbrella body of 69 Anjumans, later intervened in the petition to ensure that non-Parsis are not allowed inside the fire temple.

This gender prejudice is further bolstered by land and money, and control over the various trusts and assets.

“We allot houses to young Parsis, and are allocating houses in accordance with the legal definition of who is a Parsi now. If we change that and open the religion up, everyone will want to sign up and get cheap housing in Mumbai,” said a trustee of BPP. Rent in some of the BPP owned flats can be as low as Rs 36.

This is a long held argument and came up even in the Davar Beaman judgment, which said Parsis’ fear that ‘juddins’ (a derogatory term for non-parsis) would be attracted to the religion if the community’s doors are opened because of the many assets they possess.

“The funds of 50 odd lacs of rupees, richly-endowed Institutions for poor Parsis, comfortable homes for the blind and infirm, Dispensaries, Sanitariums, Convalescent homes, would attract many thousands of the most objectionable people,” said the judgment.

Caste purity over existence

The casteism followed by Parsis in India shocked a young Avesta Irani, when he came to India 20 years ago, fleeing persecution in Iran.

“I couldn’t believe it. Nowhere in the world will you find Zoroastrians disallowing people from entering Agyaris, but in India,” says Irani, who is the head priest of Asha Vahishta Agiary in Pune, a fire temple established in 2017. It’s the only temple in India where people of all faiths are allowed to worship.

The Asha Vahishta Agyari (Zoroastrian fire temple) in Pune | Shubhangi Misra | ThePrint

According to Vispy Wadia, the president of the Association of Inter-Married Parsis, the community’s attitudes have become so orthodox because it co-opted Hinduism’s rigorously hierarchical caste system.

“When we (the Parsis) came to India, there was a watertight caste system in place, every caste had its own institutions and temples. We adopted the same culture and decided who can come to the temple and who can’t,” said Wadia, who set up the Asha Vahishta Agiary.

Here, non-Parsis can light a lamp for the god worship in front of the holy fire while the priests perform a small prayer. Nowhere else in India, Wadia claims, is such access allowed in Agyaris.

Inside the temple, there are posters of the many reform-friendly priests like Jamaspji Minocherji Jamaspasa, who performed Navjote ceremonies of children of intermarriage way back in 1882. His son Khaikhuroo Minocherji Jamaspasa ordained the marriage of JRD Tata with his French wife Thelma in accordance with Zoroastrian tradition.

Wadia pointed out Parsis continue to follow the rigidity of the caste system, “By saving the so-called purity, we’re sacrificing our religion,” he added.

The preference to racial purity in the face of extinction was criticised by Parsiana in a 2019 editorial.

“If our numbers were large enough and a substantial number of people were debarred entry and participation, one could carry on. But when our fire temples are devoid of worshippers, our hospital beds and dharamshalas are empty, perhaps we should take a leaf from our once Parsi-only schools that all became cosmopolitan rather than close their portals.”

Irani cites another example of Zoroastrians co-opting caste. “There’’s no restriction in Zoroastrianism on who can study to become a priest,” he says. “Except in India. Only sons of priests can become priests, and I am shocked to see there are no female priests at all.”

Avesta Irani, head priest at Pune’s Asha Vahishta Agiary (Zoroastrian fire temple) | Shubhangi Misra | ThePrint

The attitudes are changing, Parsis argue. In a relatively wealthy, educated community, the orthodoxy of the past has been left behind. “It is an open secret that women and their children enter agyaris,” Wadia says, “but officially it’s not allowed.”

So they turn to the Asha Vahishta Agiary in Pune. Families from across India—Gujarat, Kolkata, Bengaluru—come here for the Navjote ceremony of their children. There are women who married outside the community, and have never been able to introduce their children to the temple of their faith. Tears roll down their cheeks as they pray at the temple for the first time, together.

Nobody is left behind.

This ground report is the first in a series.