Twelve years ago, Homyar Nasirabadwala was working as an accountant in his hometown of Mumbai, India, when he came across a job advert in a Parsi magazine seeking a full-time dasturji, a Zoroastrian priest. Already ordained in doctrines dating back to antediluvian Persia that influenced essential principles of Judaism and Christianity, Nasirabadwala figured it might be time for a change, so after 11 years of number-crunching service at Shapoorji Pallonji & Co, he applied online.

Article by Rhea Mogul | South China Morning Post

There was just one catch, the posting was not at the Wadia Atash Behram, the fire temple on Princess Street, near Nasirabadwala’s home in Malabar Hill, an affluent Mumbai neighbourhood in the shadow of the Parsis’ most well-known monument, the Tower of Silence. It was 4,300km away, in Hong Kong.

“I wanted to give back to my community,” says 65-year-old Nasirabadwala, tending to a fire inside the prayer hall of the Zoroastrian Building at 101 Leighton Road, in Causeway Bay, “so I took early retirement and packed my bags. This has been the best decade of my life.”

The aroma of burning sandalwood fills the spacious, rectangular room on the fifth floor of the building. At the far end on the left, a glass panel is etched with an image of Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism. Opposite this, on the far right, a large portrait of Parsi businessman Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy covers most of the back wall.

The Tower of Silence in Bombay, circa 1955. Photo: Getty Images

Nasirabadwala places a piece of sandalwood on the flame burning in the afarganyu, a traditional silver chalice-shaped vessel that holds the fire representing purity, the light of God and an illuminated mind. This Hong Kong fire has been burning since 1993, when the 22-storey building, formerly a modest three, opened its doors on March 21 of that year, on Navroze, the Parsi New Year.

Once he got the job, there was an additional requirement: the priest had to be comfortable conducting religious ceremonies for a “progressive community”, blessing interfaith marriages, as well as performing the Parsi initiation ceremony, the Navjote, for children of interfaith marriages.

These are practices unusual if not blasphemous to the insular, conservative Parsis in India, who practise endogamy, marrying only within their community, and believe any dilution of their faith is sacrilegious, which goes for genetics, too. Children born to only one Parsi parent are not recognised. Add low fertility and late marriages to the equation, and only 150,000 or so of this ancient bloodline remain worldwide.

In 2017, the BBC reported a “glimmer of hope” in India upon the birth of “the 102nd baby” born to two Parsi parents owing to a government scheme launched in 2013 to promote purity in procreation – a “moment for celebration in the dwindling community”. As far back as 2006, The New York Times ran the headline “Zoroastrians keep the faith, and keep dwindling”. The article described a “palpable panic” among Parsis “fighting the extinction of their faith”, and thereby, for their very existence.

And yet, in Hong Kong, nearly 12 years after heeding his call, Nasirabadwala serves a Parsi population that has, in the past 40 years, according to a local Parsi directory, grown by 36 per cent – and without any need for government incentives. How is this possible?

When Nasirabadwala arrived in Hong Kong, he was unaware of the vital role that the Parsis had played in the growth of the city.

“Living in Bombay, I knew what they did for Bombay,” he says, “but on taking up my assignment to Hong Kong, I learned so much more.”

Kotewall Road, Bisney Road and Mody Road are all named after Parsi businessmen. Two of the founding members of HSBC were Parsi. The University of Hong Kong was solely funded by Hormusjee Naorojee Mody, who was also instrumental in founding the Hong Kong stock exchange, Kowloon Cricket Club and Hong Kong Jockey Club.

The Star Ferry was founded by Dorabjee Naorojee Mithaiwala. Ruttonjee Hospital, founded by businessman and philanthropist Jehangir Hormusjee Ruttonjee, is among the most recognised medical facilities in the city. He also established Hong Kong’s first brewery.

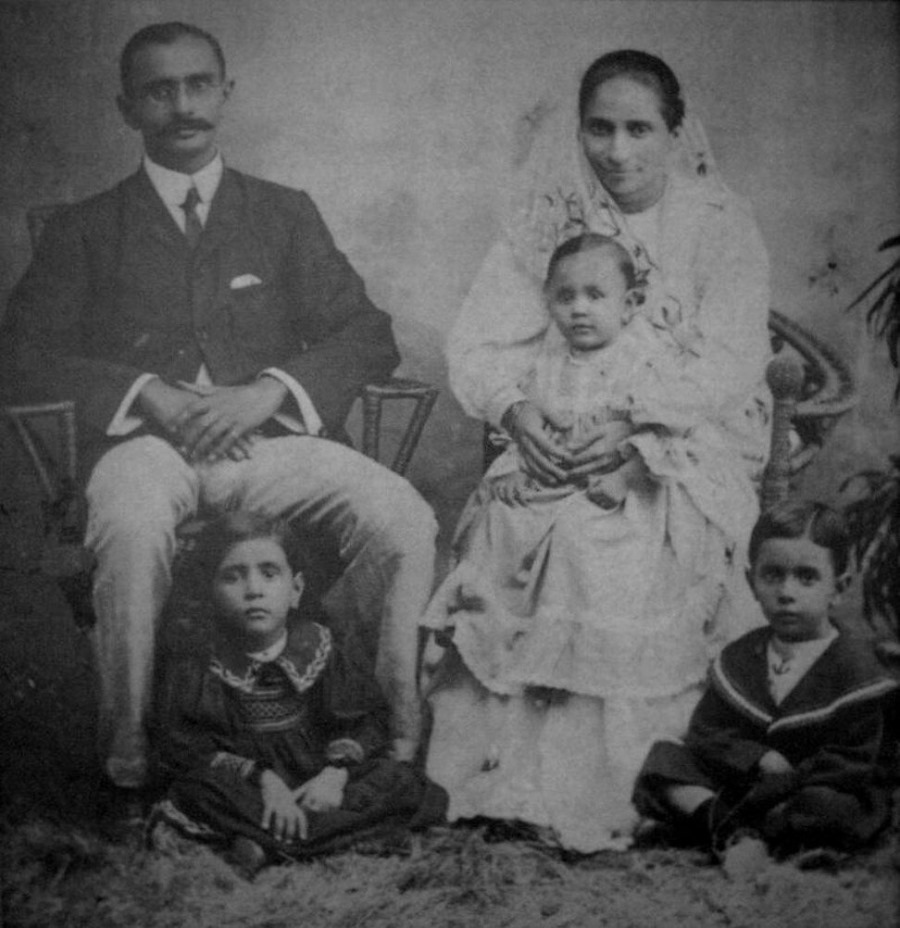

Jehangir Hormusjee Ruttonjee with his family. Photo: Handout

It is a pioneering spirit that dates back to the 7th century, following the Arab conquest of Persia, when Zoroastrians found their way to the northwestern state of Gujarat, in India. Referred to by the Indians as “Pars”, meaning “from Persia”, the Parsis were given refuge by Hindu kings on the condition that they abstain from proselytising.

Mumbai later became the centre of their world. There they built fire temples and the Tower of Silence, where the dead are left to be devoured by vultures, a practice originating in a belief that the dead should not pollute the Earth.

Settled in India, many Parsis became small businessmen, and they rose to prominence with the arrival of British rule. Lighter skinned, educated and gender-equal, they were a good fit with the British ambition to westernise India. Soon they were dominating business in Victorian Bombay, building the city’s first universities and hospitals.

Now they had their eyes set on the Far East. But before Hong Kong, it was Canton, modern-day Guangzhou, that served as the region’s trading hub. This is where the first recorded Parsi merchant, Heerjibhoy Jivanji Readymoney, arrived in China in 1756, after three months aboard a large clipper from India.

As the monopoly of the East India Company ebbed, more Parsis joined the thriving trade of the Pearl River Delta. The most well known is Jeejeebhoy, the opium trader who, in 1857, would become the first baronet of Bombay. The fortune he amassed throughout his years of trading opium would earn him the moniker “Bombay’s most worthy son”.

The old Zoroastrian Building at 101 Leighton Road, circa 1931, the year it opened. Photo: courtesy of Yazdi Parekh

On his fourth trip to Canton, during the throes of the Napoleonic wars, Jeejeebhoy was captured by the French along with a young Scottish doctor, William Jardine. Later, when Jardine set up Jardine Matheson, in 1832, one of Hong Kong’s original hongs, Jeejeebhoy was appointed as the only Asian director of the company. His portrait still hangs in the company’s headquarters in Central.

He and other young entrepreneurs like him were aware of the risks they were taking. In the Parsee Cemetery in Happy Valley, two tall tombstones pay homage to two brothers lost at sea off the coast of Macau. They were in their early 30s.

Most Parsis who travelled to China did arrive, although it took a long time for them to be accepted by the Cantonese. Having escaped religious and political persecution in Persia to settle on the west coast of India, Parsis were used to playing the long game. The Chinese referred to Parsis as bai tou yi (“white-head foreigners”), and since the social rank of any foreigner was below that of a Chinese, they had little to do with each other outside the business realm.

In Zhang Kan, a collection of essays published in 1976, Shanghai-born writer Eileen Chang says of the era: “Chinese people were very conservative. Men would never think of marrying a person of mixed blood, not even as a concubine.”

But as the Parsi presence grew in the region, so did their desire to establish themselves officially. In 1822, on the rugged slopes of Guia Hill, in Macau – now called Estrada dos Parses – the first Parsi land was purchased to build a cemetery. Twelve years later, the China Canton Anjuman, an official group to take care of Parsi affairs, was formed.

Marriages between Chinese and Parsees were not marriages of convenience; they served no political purpose. They were the results […] of the two communities getting to know and appreciate each otherGuo Deyan, historian

Not long after, stronger ties with the locals were forged. When the Treaty of Nanking was signed in 1842, ending the first opium war, manyParsis diversified into cotton, silk, tea and sandalwood.

As a result, according to Chinese history scholar Guo Deyan, the Parsis had more opportunity to interact with local people. Language barriers gradually diminished as more Parsis learned Chinese and the Chinese learned colonial-standard English. A sign of this mutual acceptance, according to Guo, was the growing practice of interfaith marriage between Parsis and the local Chinese.

“In the early twentieth century, and even earlier, marriages between Chinese and Parsees were not marriages of convenience; they served no political purpose. They were the results […] of the two communities getting to know and appreciate each other over a long period of time,” writes Guo, in his research paper, “The Study of Parsee Merchants in Canton, Hong Kong and Macao.”

Chang, in the foreword to Zhang Kan, writes of the marriage between a Chinese woman, Mi Ni, and a Parsi man named Banaji in the early 20th century in Hong Kong. Banaji, writes Chang, spoke “fluent Chinese” and was “quite wealthy”. (Banaji would become a source of artistic inspiration for Chang; his life would inform her 1944 serialised novel, Lianhuantao.)

While this marriage was viewed positively in Hong Kong, and even encouraged by Mi Ni’s mother, the laws of India made things more difficult. According to the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act of 1936, “marriage” meant a marriage between Parsis.

In 1908, a French woman, Suzanne Brière, also known as Sooni Tata, as the wife of Parsi industrialist Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, requested that after death, her body to be left in Bombay’s Tower of Silence in accordance with Parsi tradition. After her marriage, she had converted to Zoroastrianism by undergoing an initiation ritual performed by a priest, but whether this conversion was permitted was in dispute, orthodox hardliners believing one must be born into Parsism.

Brière took her case to the Bombay High Court, where Justices Dinshaw Davar and Frank Beaman concluded that the Parsi community consists of Parsis who are born of Zoroastrian parents who profess the Zoroastrian religion; Iranis from Persia professing the Zoroastrian religion; and the children of Parsi fathers by “alien” (non-Parsi) mothers who have been admitted into the religion. The legal definition excludes the children of Parsi mothers by “alien” (non-Parsi) fathers. Brière’s body lies in Paris, in the Père Lachaise Cemetery; a testament to her defeat.

Banaji, who grew up on foreign soil, and whose peers included other Indians, British, Chinese, Portuguese and Jews, rebelled against the pressure from Parsi society and, against Parsi tradition, had a son with Mi Ni. “Such enormous changes in the traditional attitudes of both Parsees and Chinese,” writes Guo, “are powerful evidence of the extent to which Parsees were accepted into Chinese society.”

This non-endogamous group set the bar for the forward-thinking Parsis who followed, which is one of the reasons the Parsi population in Hong Kong has continued to grow.

The Parekh family, who maintain the local Parsi directory, enter the names of every person – the non-Parsi spouses, and the children of non-Parsi spouses, included – who wishes to be added to the list; a very different approach from that taken by some of their Indian counterparts.

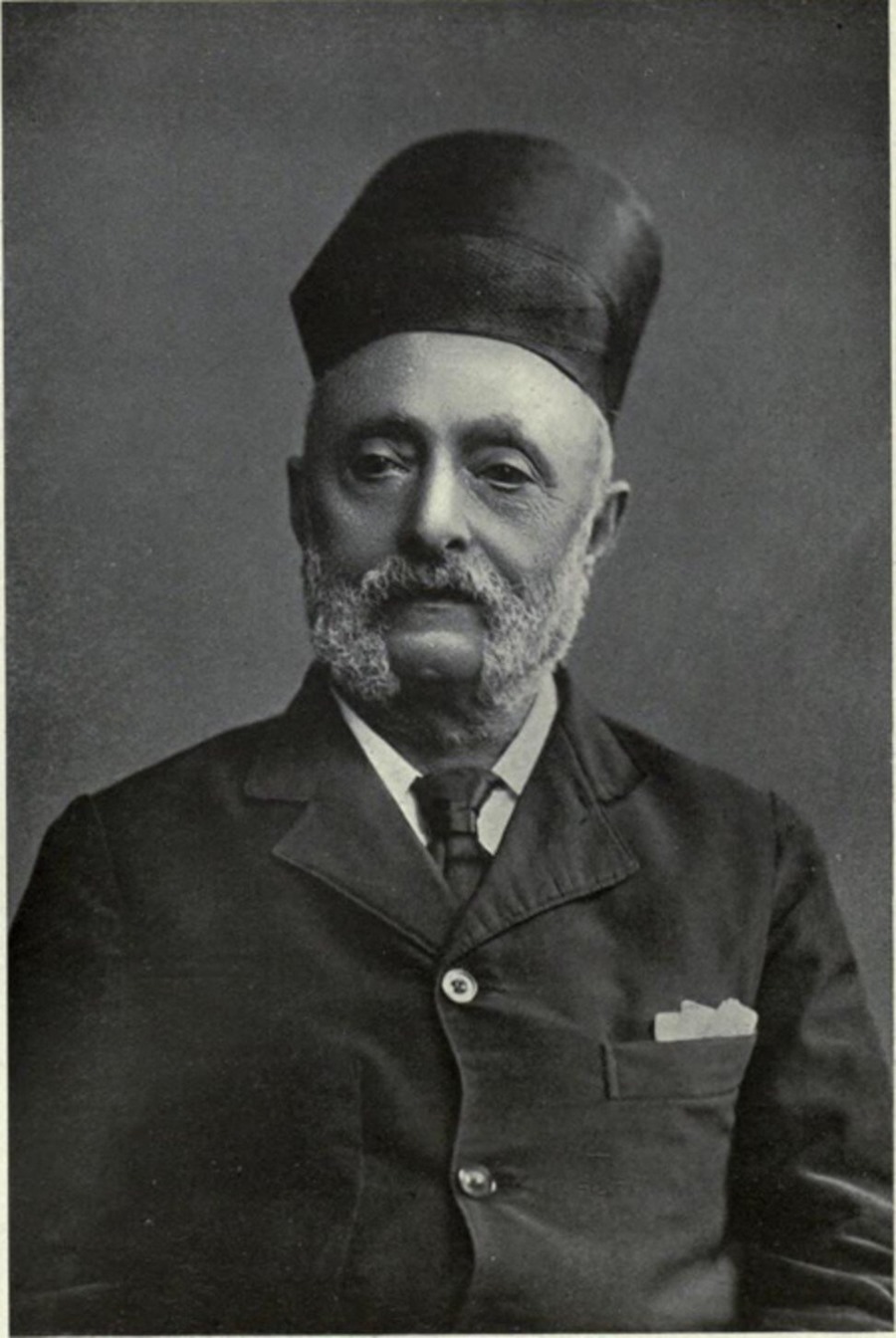

Hormusjee Naorojee Mody. Photo: Wikipedia

Four Parsi merchants – Dhunjibhoy Ruttonjee Bisney, Hirjibhoy Rustomjee, Pestonjee Cowasjee and Framjee Jamsetjee – were among the first land buyers in Hong Kong. By 1845, the Anjuman had grown to cover Hong Kong and Macau. Seven years later, the foundation stone for the Parsis’ first establishment in Hong Kong, also a cemetery, was laid at 39 Tai Ha Street in Happy Valley, today Wong Nai Chung Road.

By 1860, 17 of the total 73 merchant firms listed in the Hong Kong Directory were Parsi. The Parsis would go on to devote their time, energy and money to building much of their new home. Zoroastrian House – a three-block, 13,795 sq ft property at 49 Elgin Street, then wide, leafy and home to many Indians – was purchased in 1861. In 1931, eight years after this property was sold, Zoroastrian Building opened at its current location at 101 Leighton Road.

Mody, a Parsi businessman who was once described as “a prince of good fellows” by the headmaster of Oxford University’s Queen’s College during a Hong Kong visit, is arguably the most illustrious example of his kind. He solely financed the building of the Kowloon Cricket Club, on Cox’s Road, in Jordan, in the 1900s, and was one of the founding members of the Hong Kong Jockey Club.

His horses – Fun and Marauder among them – won the Hong Kong Derby 11 times. But of all Mody’s contributions to Hong Kong, the greatest remains his role in founding HKU, donating HK$180,000 towards its cost. The foundation stone for the university was laid on March 16, 1910.

“We’ve been here for a very long time,” says 88-year-old Noshir Pavri, a Hong Kong-born Parsi. “And we’ve made the city our own.”

The foundation stone laying ceremony of the University of Hong Kong, on March 16, 1910. Photo: University of Hong Kong

Pavri’s grandfather arrived in Canton in 1910 for the same reasons as many Parsis before him: to trade and start businesses. In 1924, the family migrated south to Hong Kong. They lived in Wyndham Street, notable for its strong Indian presence. Their office was on the ground floor of their home; Noshir, his sister, Ruby, and their parents lived on the upper floors.

“This is how every family-owned business did it,” says Pavri. “We’d go downstairs to work in the morning, leave after finishing. It was a simpler, easier time.”

These “simpler” times would soon come to an end – for three years and eight months, to be exact – and the Parsis would experience an unimaginable reality.

When the Japanese invaded Hong Kong on December 8, 1941, many foreigners fled the colony. Under the new rule, Hong Kong bank accounts were frozen, the value of the Hong Kong dollar shrunk by 25 per cent and the local Anjuman fell on hard times.

“Although the Indian community, the Portuguese, and other ‘neutral’ nationalities were allowed to live ‘at liberty’,” says Pavri, “it was quite a deceptive freedom, as there was inflation, rations, bombings and raids. Our standard of living and quality of life had dropped significantly.” Individuals were imprisoned for offences such as keeping lights on, or for being outdoors during curfew. “There were tunnels along what is now Queen’s Road East, where people would hide. People sold personal items, bit by bit, to get by.”

Zoroastrian priest Homyar Nasirabadwala in the Zoroastrian Prayer Hall at the Zoroastrian Building, in Causeway Bay. Photo: Antony Dickson

Pavri’s Wyndham Street home and the Ruttonjee home in Duddell Street were used to house Parsis who had been deprived of their own homes. Several Parsis were imprisoned by the Japanese, Ruttonjee among them.

Together with his sons, Ruttonjee was accused of helping the internees of Stanley camp, and of engaging in anti-Japanese activities. In 1942, Japanese guards surrounded their homes, Dina House and Ruttonjee Building in Duddell Street, for several weeks. The men spent nine months in prison on remand, were tortured and then sentenced to five years’ imprisonment.

Despite the harrowing conditions, the Anjuman’s focus on serving the Parsis remained. Accounts from meetings held between 1941 and 1945 tell of how the organisation was in dire need of money, unable to withdraw any from its accounts. Many Parsi residents took it upon themselves to pay for the Zoroastrian Building’s upkeep – electricity, water bills and the salaries of the priest and the cook. Parsi businessman Rustamba Dastur described it as his “duty” to give his own money, and to see that their cemetery received “protection, always”.

So on August 30, 1945, when the Japanese surrendered, a jubilant Pavri and his family took to the streets for a “momentous celebration” near Admiralty.

With time, Hong Kong had become deserving of the sacrifices made in its name. Its diverse community learned to work together, forging lasting partnerships. Hong Kong was a city worth fighting for. And 43 years later, so it was again.

Jal Shroff at the Kowloon Cricket Club. Photo: Antony Dickson

The idea to redevelop the three-storey building at 101 Leighton Road was sown in the minds of the community by former Anjuman president, Jal Shroff, in 1988.

“A lot of people were against the idea,” says Shroff, who arrived in Hong Kong in 1949 as a refugee from Shanghai. His father “lost everything” when the Communists took over. Reflecting on the colony’s handover, he says, “It was an uncertain time, and people didn’t know what would happen to Hong Kong after 1997,” says Shroff. “There was a lot of fear.”

When the Tiananmen Square crackdown occurred in Beijing in 1989, “it put an entirely different perspective on the commercial viability of the project”, recalled Hong Kong-born Parsi Jimmy Master, in an interview with Parsiana magazine during the opening ceremony of the new Leighton Road building, in 1993. When tenders were put out, the response, according to Master, “was dismal”, but the redevelopment went ahead.

The building would “maximise the plot ratio, earn a significantly higher income for the trust funds, and enhance facilities available for the local Anjuman”, said Master. But most importantly, the structure represented a “reaffirmation of the community’s future in Hong Kong”.

So in 1993, Shroff inaugurated the new Zoroastrian Building, which “today reflects the efforts of a community that has worked together for a common cause”, he told a crowded room. “We, the Parsis of Hong Kong, [are] demonstrated by not our words, but by our actions and our commitment to Hong Kong.”

Neville Shroff, president of the Hong Kong Anjuman, with his wife Farida and their children Alisha and Nigel, at the Clock Tower in Tsim Sha Tsui. Photo: Antony Dickson

And that year, days before Shroff gave his speech, a time capsule was buried under the lobby entrance. “Who among us will be left in Hong Kong to open the time capsule? From the 40 children in our community, who will choose to make Hong Kong their home? And among the younger families, will they continue to make a home for their growing families in Hong Kong?” These, according to Master, were some of the questions being pondered by the community’s older generation.

Twenty-six years later, in 2019, Alisha Shroff walked onto a stage at the Pacific Palms Resort in Los Angeles, in the United States, part of a seven-person panel to discuss how “women will modernise the world’s oldest religion” at the World Zoroastrian Youth Congress.

“I love to explain to people that Parsis and Hong Kong have actually had a long and very enterprising history,” she says.

Shroff, 36, is fourth-generation Hong Kong-born, the oldest of three siblings; brother Nigel and sister Natasha were also born and raised in the city. Her father, Neville Shroff, has been president of the local Anjuman since 2011.

“A lot of thought has to be given to planning what’s next,” she says, sitting in the Italian restaurant at the Harbour Club, in Tsim Sha Tsui. “We have to find a way to bridge a gap and find a common ground for our need to modernise our religion, and what mindset needs to change.”

In the distance, the Star Ferry makes its way across the harbour.