The ambitious project opens the scriptures of seven faiths to anyone who wishes to learn

Article by James Christie | Broadview

Once upon a time, a mere six centuries or so before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, the world’s greatest religious traditions emerged from what German philosopher Karl Jaspers called the Axial Age. The dating is under some debate, but from approximately 650 BCE* to 400 BCE, religious creativity exploded across the ancient world — in India, China, Persia (Iran), the Eastern Mediterranean Basin and the Greek peninsula — leaving a legacy of philosophy, religion, ethics and faith that continues to inform, rock and shape our world and our future.

Karen Armstrong, arguably the greatest living writer in theology and religion in the English-speaking world, called for a new Axial Age in her 2006 masterwork, The Great Transformation. Never, she argued, has the human community required positive and collaborative religious leadership more than it does now.

During the last decade, Rev. Brian Arthur Brown, a United Church minister, has offered one answer to Armstrong’s call. With a team of international multifaith scholars and writers, he has published an ambitious trilogy: Three Testaments (2012), Four Testaments (2016) and Seven Testaments of World Religion and the Zoroastrian Older Testament (2019).

The underlying concept of what might be described as the Testaments Project is as brilliant as it is simple. In Three Testaments, the core sacred texts of Judaism, Christianity and Islam — the Torah, the Gospels and the Qur’an — are opened side by side, with none having priority or prejudice over the others.

The exercise was reiterated in Four Testaments. In this volume, four eastern religious texts are presented both for the scholar and the interested layperson: the Tao Te Ching (Taoism), the Analects (Confucianism), the Dhammapada (Buddhism) and the Bhagavad Gita (Hinduism).

Seven Testaments is a different animal. Describing it as a prequel, Brown and his team tease out what the initial two volumes hint at, focusing on the Zoroastrian tradition.

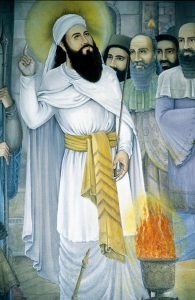

Remember the Magi from Matthew’s Gospel narrative of the Nativity? Their visit forms the basis for the season of Epiphany. Three wise men, kings if one prefers, follow a star until it rests over a stable near Bethlehem. Tradition endows them with three gifts: gold, frankincense and myrrh. Tradition also designates them as Zoroastrians, followers of Zoroaster, or Zarathustra.

The origins of Zoroastrianism are shrouded by time and circumstance. It is said to be among humanity’s most ancient traditions. Some contemporary scholars date Zarathustra to sometime in the second millennium BCE, but others, including Brown, believe he lived about six centuries before Jesus. The Persian prophet’s teachings emphasize monotheism and a spiritual world that is the eternal model of our material world.

Zoroastrianism was of immense influence in ancient society. It was the state religion of Persia until the Muslim expansion of the seventh century CE. As Islam attained pre-eminence, the followers of Zarathustra migrated to India, becoming identified as Parsis.

With between 100,000 and 300,000 adherents worldwide today, according to recent estimates, Zoroastrianism is practised as a minority faith tradition in parts of India and Iran. There are also North American outposts, notably in Toronto and Washington, D.C.

And Zoroastrianism may have an even bigger modern presence if you know where to look. Scholars have long wondered at the striking parallels, even commonalities, among the seven world religions discussed in the trilogy. Jesus and the Buddha appear to have heard the same stories at their mothers’ knees.

Perhaps, Brown suggests, there was a proto-religious tradition that underlies all our sacred texts. Perhaps that early scripture is a compilation of the Zoroastrian sacred writings, known as the Avesta, and the ancient Vedas of the Hindus. Perhaps these teachings made their way along the ancient Silk Road, the world trade route stretching from Morocco in northwest Africa to the far reaches of China. Perhaps, if the ongoing archeological expeditions to Afghanistan in search of Zarathustra’s tomb are successful, we may be able to retrieve lost and only imagined fragments of the Avesta. It would be a discovery of the magnitude of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran in 1947.

Whimsically, but with merit, Brown refers to such a possibility as the “Dead Zee Scrolls.”

If such a textual ancestor exists, and is unearthed, it would not for a moment suggest that all religions are the same. It would not result in some form of shallow, hipster syncretism. It would neither dilute nor diminish the sacred texts, scriptures or religious uniqueness of any of our great faith traditions.

But it would suggest an often imagined yet never documented unity in the ethics, hopes and dreams of the human community. It would permit the growth of what Paul Morris, of Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, describes as “cosmopolitan piety”: the holding as sacred and true our own religious beliefs while treasuring as sacred and true the beloved scriptures and traditions of others.

The consequences are far-reaching. Brown and his team have opened the scriptures of seven religious traditions to anyone who wishes to know the world’s faiths: their own and their neighbours’.

For North Americans, our neighbours and neighbourhoods have changed dramatically.

We are a country markedly secular in governance, yet religiously plural in nature. For the past two decades, our neighbour has been more likely to be a Muslim than a Presbyterian.

One of those neighbours is Amir Hussain, professor of theology at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles and among the foremost interpreters of Islam to North America. He was trained at the University of Toronto under the guidance of the eminent Islamic and comparative religion scholar Rev. Wilfred Cantwell Smith. Hussain, a contributor to the commentaries of Three Testaments, says that these volumes present sacred texts as they ought to be read, not “in isolation, but in conversation.” He further notes that the conversation must be within each tradition and between and among world religions.

Ellen Frankel, a Jewish contributor to Three Testaments, agrees. “This project holds great promise to advance the cause of interfaith understanding,” she writes in her preface to the Torah.

Kersi Shroff, a Zoroastrian community leader and retired division chief at the Law Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., is delighted at the heightened profile of Zarathustra through the Testaments Project. It has meant that Zoroastrians finally have a place at the table of interfaith dialogue.

Shroff reflects that in the classic Stanley Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick chose as the musical score Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, a piece intended to emphasize human progression. If there is to be a next step in human evolution, it must surely not be biological, but psychosocial, moral-ethical and spiritual — in short, heralding a second Axial Age. The ethos of religious collaboration and connection that animates the Testaments Project may prove pivotal to such a hope.

*In the spirit of interfaith conversation, this essay uses the abbreviations “BCE” (before the Common Era) and “CE” (Common Era) in place of the Christian-based notations “BC” (before Christ) and “AD” (anno Domini, “in the year of our Lord”).

This essay was first published in Broadview’s June 2020 issue with the title “Scripture’s Z factor.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Rev. James Christie is a minister, scholar, ecumenist, essayist and religious diplomat based in Winnipeg.