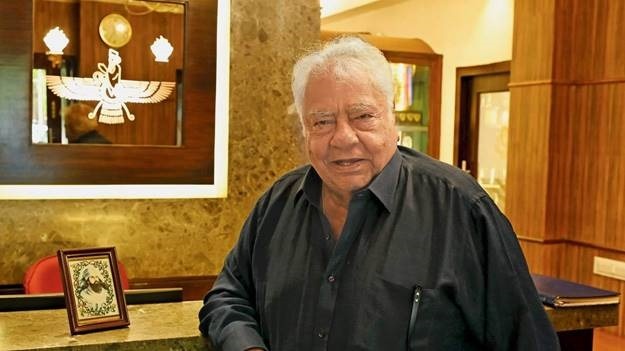

As Farokh Engineer, one of India’s cricketing greats, steps into Parsee Gymkhana on Friday afternoon, the sea-facing club bears a near deserted look, with just a handful of youngsters in whites playing at the nets. And it’s not just the club from where the Parsis have gone missing. From a community that pioneered the sport’s growth in the country, Parsis have been slowly disappearing from the sport over the last few decades. Ironically, even Parsee Gymkhana’s own team, which figures in the ‘A’ division of the famous Kanga League, features not a single Parsi player.

Article by Debjani Paul | Mid-Day

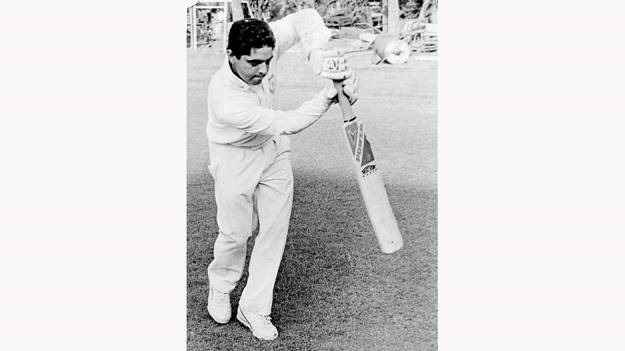

Farokh Engineer, visiting Mumbai from the UK, recounts the glory days of Parsi cricket at the Parsee Gymkhana at Marine Lines during a visit last Friday. Pic/Ashish Raje

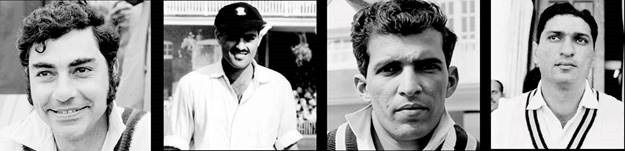

Few feel this absence as keenly as 86-year-old Engineer, who hails from the glory days of Parsi cricket, when the community had contributed not one, but four of the 11 players in the Indian Test team during the 1961-62 tour of West Indies—Nari Contractor, Polly Umrigar, Rusi Surti and Engineer, all giants of the game. Engineer remains the last Parsi to have played for India in men’s cricket.

“Why aren’t more young Parsis coming up in the game? I wish I knew. Perhaps youngsters are not willing to work hard, or perhaps they are more interested in other things. Our community is a microscopic minority, but if we were able to produce four out of 11 cricketers on the team at one point, surely you’d expect someone new to have come up by now,” rues the flamboyant wicketkeeper-batsman, who now resides in the UK and is in Mumbai on a visit.

Fredun de Vitre and Diana Edulji

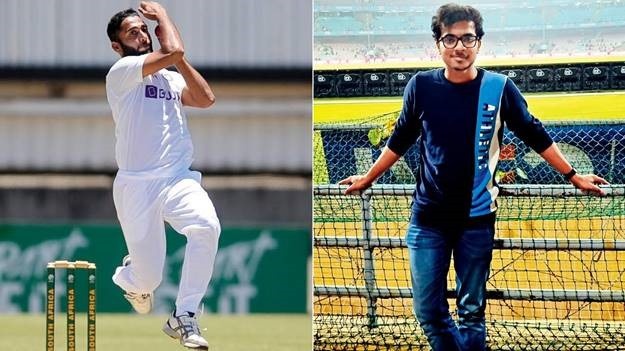

A new documentary, Four on Eleven: The Fading Glory of Parsi Cricket, seeks to explore this very mystery. Filmed by Xavier Institute of Communications (XIC) alumnus Shrikaran Beecharaju, 23, the documentary is currently being screened at the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne (IFFM).

Narrated by former commentator and Doordarshan broadcaster Fredun De Vitre, the film traces the beginnings of cricket in India, elaborating on how Parsis established some of the earliest clubs in the country—many of them in Mumbai. The very first Test team from India to tour England in 1886 was entirely composed of Parsis. De Vitre recounts how the angliophile community originally picked up the game as a way to “get into the good books of the British”, but as they started to do well, it became a way of “striking back” against the Empire.

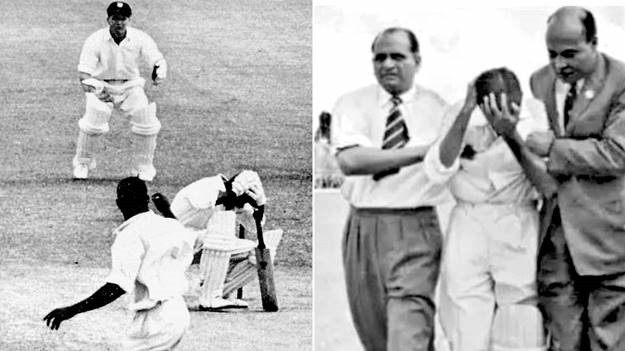

The film then moves on to the 1960s and ’70s—this was long before cricket became India’s national obsession—when Engineer and his ilk stepped up to the crease and put the country on the global cricketing map. It touches upon a seminal moment in cricket history, one that is etched in the memory of all Indian fans: when Nari Contractor was hit on the head by a delivery by Charlie Griffith at Barbados in 1962, and walked off the field. After a surgery to repair a skull fracture, his international career had come to an end, but he continued to play first-class cricket. Contractor is held up as an example of Indian cricketers’ grit to this day.

The documentary also mentions the contributions of other greats from the community, such as Diana Edulji, who still holds the record for most balls delivered by any woman cricketer in Test history. She is also the last Parsi to have played for India in women’s cricket.

The documentary is named after the eponymous four on the Indian team of XI that toured the West Indies in 1961-62. Pics courtesy Four on Eleven: The Fading Glory of Parsi Cricket

From the heights of the community’s achievements in the game, the documentary shifts to its lowest point in the second half, highlighting how not a single Parsi player has reached the top levels of the game in recent years.

For Beecharaju, an avid fan of the game, when the time came to make his student film, cricket was an obvious choice. “When I was researching cricket history, I learned that Parsi players in the ’60s and ’70s revolutionised the game in Bombay. When I arrived in Mumbai to study at XIC, my campus [at Fort] was very close to Parsee Gymkhana. I decided to just walk in one day, knowing absolutely no one at the club, and told them that I wanted to make a film about Parsi cricket. I reached out to Farokh Sir and [Gymkhana vice-president] Khodadad Yazdegardi. Fortunately, they helped me,” recalls the filmmaker, who now resides in Hyderabad, working as an assistant director in the Telugu film industry.

What was meant to be a 15-minute student film became a passion project for the youth, who researched cricket history, chased down prominent names for his film, shot them and edited the film over the course of 10 months, pouring his entire earnings in that period into making the hour-long film.

Arzan Nagwaswalla, 26, is the sole Parsi cricketer playing at the national level, and is the first from the community to reach this level since Farokh Engineer; (right) As a cricket fan, Shrikaran Beecharaju was fascinated by the sport’s history in India and chose this as the subject of his student film while studying at Xavier Institute of Communications

“I featured nine people as the main faces of the film, and it took a long while to edit it and build a narrative around their interviews. Noise was also an issue, since most of the interviews were conducted on field or in crowded clubs, but we used AI to clean it up,” says Beecharaju.

For the Hyderabad youth, it’s an honour to see his film being screened at an international platform like IFFM, but he hopes to bring it to Indian viewers as well, once he can raise the funds.

“This film is an effort to spread the word about the contributions of the Parsi community to Indian cricket. Even avid fans might not be aware of this history. This film can be a starting point for anyone who wants to know more about the game’s evolution in the country,” he says.

Nari Contractor walks off the field after being hit on the head by a delivery by Charlie Griffith at Barbados in 1962. This moment in cricketing history is etched into Indian fans’ memory as an example of Contractor’s grit. Pics/mid-day archives

For Engineer, the hope is that the documentary reaches out to the younger members of the community and inspires them to don whites. “When the young man [Beecharaju] reached out to us, we agreed to feature in his film because we thought it might inspire the younger generation. It doesn’t matter at what level they play at, as long as they have a burning desire to do well.”

The film explores several possible reasons why younger Parsis are not showing an interest in the game, whether it’s academic pressure, parents’ apprehensions of whether it makes a stable career or simply a wider range of sports to choose from.

De Vitre ventures that “perhaps it’s tied to increased affluence in the community”, with Parsi numbers dropping not just in cricket but all kinds of sports. “Ironically, the older generations still go and play at clubs and enjoy the game. You don’t have to play at the highest level, just enjoy the game at whatever level you play. And the more you play, the more likely it gets that someone from the community will rise to the top of the game. We have a seniors team—all above 50—at Parsee Gymkhana. But we don’t see the same enthusiasm among the youth,” he adds.

“Maybe they’ve had too much dhansak,” jokes Engineer, adding that he does not see the same grit of yore. “I used to come from Dadar to CCI to practise and would hang off the trains, just missing the telegraph poles by inches. I’d carry my heavy kit bag and walk back from Dadar station to Dadar Parsi Colony. It wasn’t easy, but I was determined to make something of myself. Unless you have that burning ambition, in anything, you won’t succeed.”

In the documentary, a single name spells hope for the community—Arzan Nagwaswalla, a left-arm pacer from Gujarat who is the first Parsi to play at the national level since Engineer. In 2021, he was also picked as a stand-by player for the Indian squad touring England, but Engineer’s streak as the last Parsi player at the international level remains unbroken, as Nagwaswalla didn’t get to play.

The 26-year-old, who hails from Nargol village in Valsad, feels both pride and the weight of expectations riding on him. “I feel proud that after Farokh sir, I am the first Parsi to have made it to the national level, but I also feel responsibility to uphold the legacy of the greats who have come before me, he says, adding that he is the only Parsi playing at the Ranji level as well.

“The Parsi population is shrinking every year; there are very few young Parsi boys left to take up any sport. There were no Parsis in my school [Jadi Rana High School in Valsad, on the border of Gujarat and Maharashtra] either. The only Parsis I know are in Mumbai, and all are either pursuing academics or jobs or their family business. Sports is not a serious career option for young Parsis,” he adds.

“Arzan is a lovely bowler. I was delighted when he was inducted in the Indian squad, but was not happy that he didn’t play. But that’s how it happens—[sometimes one is] so near and yet so far. But at least he’s in the selectors’ minds. To be selected for an international tour is a wonderful thing,” says Engineer.

For now, the wicketkeeper still waits to pass on the baton—or the gloves—to the next generation. “I’m sick and tired of hearing that I’m the last Parsi to play Test cricket for India. I would love nothing better than for someone to come and break that record.”

Zubin had the zing, but not the India cap

Zubin Bharucha

No male Parsi has been able to earn an India cap after Farokh Engineer played his last Test in 1975. But a section of the Mumbai cricketing fraternity believes opening batsman Zubin Bharucha had the potential to be the next Parsi India player.

In November 1992, Bharucha, then 22, scored a hundred on Ranji Trophy debut for Mumbai against Baroda. Less than two years later, he carved an Irani Cup hundred for Mumbai at the same Wankhede Stadium to solidify his case as a future India opening batsman. Bharucha made the Mumbai Irani Cup team as he was part of Ravi Shastri’s 1993-94 Ranji Trophy-winning side.

Against Maharashtra in the league stage of the 1993-94 national championships, he scored 93 while his next best score that season was 51 in the second innings of the semi-finals against the same opponents. Four games later, his tryst with first-class cricket came to an end.

Bharucha had played for Podar College and Dadar Union Sporting Club. But before that, he had an exciting stint with Azad Maidan club, Parsi Cyclists, whom he joined as a 14-year-old. Parsi Cyclists were sad to see him go, but like in all departures, wounds heal. Coaching was an avenue he explored, experienced and excelled in. Ask Rajasthan Royals, who he has been associated with since the start of the IPL in 2008. Ditto the Sri Lankan team who profited from his recent consultation to beat India in an ODI series for the first time since 1997.

Clayton Murzello