Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry on the Parsi theatre tradition we lost

Lavish backdrops, melodramatic flourishes, high-pitched singing, complex tableaux and opulent floats — it combined European techniques with local contours to create a theatre form that became India’s first commercial venture

What interests me about the Parsi theatre movement between 1840-1930 is that even though it’s a theatre of the past, it provides a space where we can rediscover not only the art of memory, but also retrieve and reclaim our history.

It continues to haunt, making us question why it disappeared without a trace. My generation has only heard and read about Parsi theatre, not seen it, but the romance of that period lingers, conjecturing stories of lavishly-painted backdrops, melodramatic flourishes, high-pitched singing, complex tableaux and opulent floats. Parsi theatre combined the best of European techniques with local contours to create a theatre form that became India’s first popular commercial theatre. Cutting through social and religious stratification, it provided a truly egalitarian space in a country submerged in factionalism.

The name ‘Parsi theatre’ may suggest that it was a theatre that dealt with actors and narratives of the Parsi community, but that is not the case. The Parsis saw a lucrative and viable business possibility in the entertainment sector and decided to invest in this venture. They hired writers, actors, singers, dancers and technicians, creating a huge infrastructure and a mindboggling backstage team.

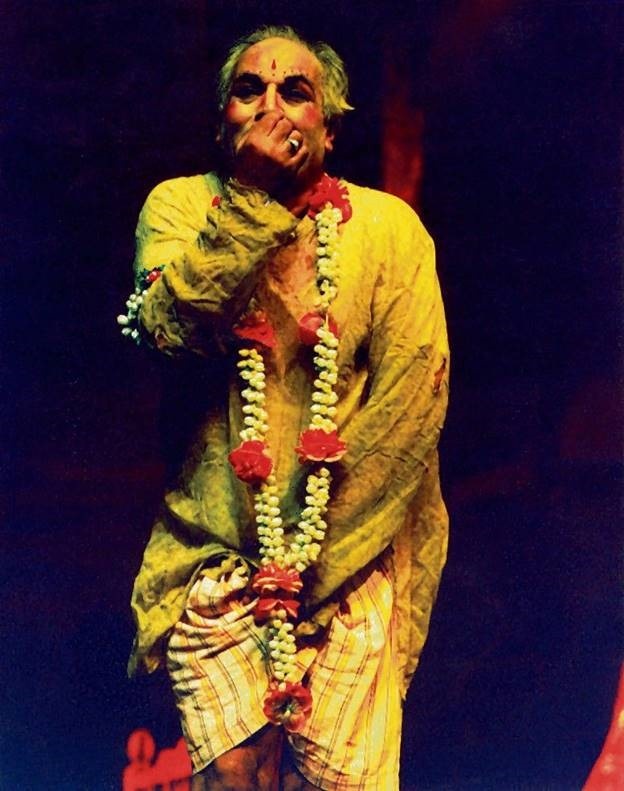

‘Begum Barve’ by Satish Alekar, 1996, director Amal Allana, designed by Nissar Allana, Manohar Singh as Barve. Courtesy: Theatre & Television Associates, New Delhi, 1996.

The painted backdrops, flying up and down with magical efficacy, had one wonderstruck. From a lush forest to an ostentatious palace, from a bustling street to a private boudoir, it made one feel as if one was on a journey. From indoor to outdoor, from mythical forests to a house of mirrors, the art of illusion was perfected by technology that allowed zero error. Snow machines and rain machines awed the audiences, who thronged the theatres and made the cash box jingle.

Each company had its own residential writer, whose scripts were guarded in a manner that would put Fort Knox to shame. Posters with sensational headlines, such as ‘See how a thief became a saint’, caught the attention of the public, their spectacular designs in lurid colours firing the imagination of the people.

The Parsi companies didn’t just work in Gujarati, Urdu, Hindi and English theatres, but inspired theatres in virtually every corner of India. The performative vocabulary was eclectic and stories were taken from Persian legendary text ‘Shahnama’, the Sanskrit epic ‘Mahabharata’, ‘Arabian Nights’, as also Shakespeare.

There was an amalgamation of techniques derived from European theatre, which were nativised by incorporating local and classical elements from Tamasha, Bhagavata Mela, Dashavatara and other forms.

The stage was set ablaze by mythological characters battling the asuras — daggers flew in the air and heroes appeared and vanished at will. It was an intoxicating mix of valour and villainy, song and dance, along with humorous asides and highly declamatory oration.

The history of Parsi theatre to a great extent became the framework through which modern Indian drama came into existence. Despite its structure being European, it managed to create a theatre that expressed national ideology, social concerns and also wove in Indian mythology and social issues.

Many significant theatre productions were impacted by Parsi theatre, but I will be referring to the two plays that I have seen: Anuradha Kapur’s ‘Sundari’ (1997) and Amal Allana’s ‘Begum Barve’ (1996). Both the plays straddled the aesthetics and impulses of Parsi theatre within the dramatic grammar of the contemporary. The protocols of illustrative gestures, grand stances and exaggerated body language were in evidence. The locking of the eyes between the lovers, the tiny quiver of the lips, the painted curtains, the magic of gaslight and reflecting mirrors were reminiscent of an era gone by.

Both the plays were in some way a bridge between Parsi theatre and modernity. The influence of Parsi theatre is evident in these two productions in the use of backdrops that manifested locations analogous to the scenes in the text.

Anuradha Kapur’s production was an adaptation of the autobiography of Jaishankar Sundari, the legendary female impersonator of the Gujarati stage in the early 20th century. One of the highlights of the play was the collaboration between the director and artists Bhupen Khakhar (1934-2003) and Nilima Sheikh. The front curtain painted by Khakhar on a diaphanous tissue allowed us a glimpse into the private world of the female impersonator, while Sheikh’s backdrops evoked memories of Parsi theatre, with fragments of images from the paintings of Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906). The system of various curtains going up and down was handled manually, as in the Parsi theatre of yore.

In one scene, Jeetu Shastri (1957-2022), as Sundari, lies down on the floor of the stage with three burning diyas placed on his bare body. This brief and fleeting moment evoked a sense of a body burning. Or was it a funeral pyre? The image haunts despite the intervening years.

‘Begum Barve’, written by Satish Alekar in 1979, focuses on the shifting gender identities of its protagonist. It was interpreted magnificently by actor Manohar Singh (1938-2002). He played the role of a penury-ridden female impersonator, who is encased in a world of illusion and smokescreens. Through a series of fragmented memories, the past overlaps with the present, and the real with the imaginary. Begum Barve wishes to escape his bleak and bland world and enter a world of music and dance. In this imagined world, Begum Barve can play the woman, be a woman, or become whoever he wishes to be. The separation of the real world from the illusionary world can also be seen as the male/female split. Trapped between sensuous longings and the sordid reality of a humdrum existence, seeking solace in the make-believe, layer upon layer of meanings — dense and opaque — emerge.

Manohar Singh played the role with a whimsical vulnerability. Clad in a wispy white dhoti, with pinkish make-up and antimony-lined eyes, he looked like a vulnerable painted doll. I recall him slowly hooking the buttons of his blouse on his imaginary breast, and wrapping a shimmering red sari around his aging body. Sitting on a swing in an attitude of yearning, he looks futilely at the audience — and an unexpected hush descended in the auditorium.

Both these productions, done under a gauzy light with painted curtains reminiscent of the Parsi tradition and characters floating in and out, created a world of moonshine and sadness and unresolved longings.

The female impersonators in both the plays understood the world through both masculine and feminine perspectives. Both the characters were remnants of Parsi theatre — when men played the role of women and internalised a ‘sense of the feminine’ to an extent that gender got obfuscated.

The Hindi film industry, known for its melodramatic acting and larger-than-life depiction of the world, has borrowed these qualities from Parsi theatre. The proscenium arch, stage machinery, stage tricks and the painted backdrops became part of the new medium. In the beginning, it imbibed the mythological subject matter, the costuming, dialogue delivery, the theatrical mise en scene inspired by the paintings of Raja Ravi Varma, all echoing Parsi theatre stylistically and structurally.

The theatre companies transformed into film companies, with financers, managers and actors from Parsi theatre becoming part of the new medium. Despite the fact that Parsi theatre morphed into bioscope and silent films, residues existed and translated into theatrical productions like ‘Begum Barve’ and ‘Sundari’. I am surprised how we let such a significant theatre movement disappear without a fight.

— The writer is a Chandigarh-based theatreperson